Modern urbanists have to be experts (or at least knowledgeable) in various fields. To name a few area of urbanism: climate change and its impact on urban heats, agricultural and suburban floodings and droughts; sustainability of materials, building processes (production, logistics, workers) and future uses of a project (mono-use, mixed-use); old and new infrastructural demands such as streets fitted comprehensively with bicycle lanes, charging points for electric vehicles, pedestrianised areas, pocket parks; higher demands for urban greenery and its diversity (“a lawn does not make a park”); increasing technological demands in terms of building processes and computer-programs needed to keep up with major architectural offices in terms of their artistic and visual output (rendering programs, BIM); privatisation of urban spaces (fencing, privatisation of residential flats as market commodity, defensive architecture); population growth on one hand and abandoned cities and the concomitant urbanisation on the other; pandemics and the necessity to provide clean, hygienic, unpolluted and healthy spaces in overly densely populated urban areas.

The list can go on, and the necessity to care about one, two, or all of the previously-mentioned issues varies from one locale to another. In this understanding of the profession of the urbanist, the urbanist is distinct from the architect and the urban planner, who is often engaged with actual (materialized) projects – instead: the urbanist is understood as the philosopher of urban space, whose task it is to think about the idea, meaning and concept of a project, serve as a consultant to a planning team or otherwise express an opinion through teachings, a magazine, NGO’s, think-tanks or any other media.

In this article, I attempt to open and widen the field of contemporary urbanism and discuss issues and potential fields of expertise that may become more relevant to urbanists (and consequently to urban planners and architects) in the future.

Reconstruction

For this area of potential expertise, two examples shall be given. In 2012, the German city of Frankfurt am Main started reconstructing part of its widely bombed and destroyed old town. Dima Stouhi summarises: “[…] [T]the collaborative work of the community and local authorities had made it seem as though time before the war stood still. The entire quarter was reconstructed exactly as its original plans, bringing Frankfurt’s medieval history back to life and creating what is now known as the Neue Alstadt, a project considered by some to be controversial. […] [T]he jury selected a winning design by architecture firm KSP Engel & Zimmermann, but a public debate was brewing on the sidelines as the reconstruction of historical old townhouses was being demanded. Many locals saw a unique opportunity to tear down the dull administrative building and its concrete walls, and restore some of the original characters of the historic city center, along with 7,000 sqm of the old alleyways and squares that were destroyed during the War.”

Another example of reconstruction, or better: the question of how to reconstruct, through which means, in which style, and by whom arose in Ukraine. In Mariupol, around every second building or more has been destroyed or damaged during the 80 days of constant bombardment by the Russians. It may be even more in Bachmut, another battlefield and one of the so-far bloodiest fights during the Russian attack on Ukraine. Ro3kvit is a conglomerate of architects, urban planners, and specialists in the field that has already started to discuss, think, and plan Ukraine’s reconstruction. They aim to “[…] [unite] their efforts to develop knowledge and methodologies for rebuilding Ukraine’s urban and rural environment and infrastructure. […] Through design and research, we address urgent needs raised by stakeholders now and connect this to future strategies. Fuelled by studies on other (postwar) countries, we are developing new, future-oriented urban design methods, co-creative organization, and sustainable development.”

We have already explored 3D-printed housing as a temporary solution to post-disaster housing, but here it is more relevant to think about how reconstruction processes can be started and managed. In the case of Frankfurt, the task seemed clear: Rebuilding what was destroyed, perhaps slightly simplified. In the case of Ukraine, the situation is more complicated. Reconstruction means rebuilding complete cities – from residential houses to cultural buildings in a short time post-war. Whether or not a building is considered necessary or worthy to be rebuilt or reconstructed will depend entirely on the financial means, needs, and experts.

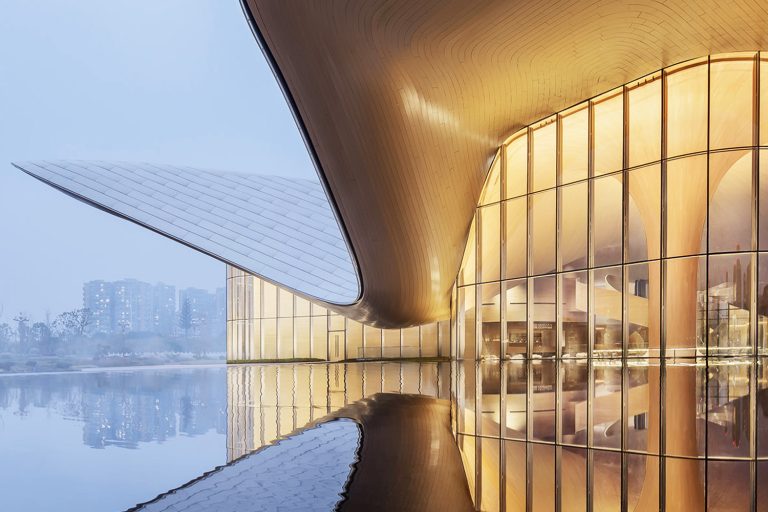

Moving away from Earth

In an article called Life On Mars, But How? A Few Architectural Considerations, we have discussed potential architecture and living conditions for life on Mars. Here, Mars architecture is understood as being the result of various constraints: getting materials there, getting robots, human builders, or self-building houses, the extreme temperatures and radiation, and the need for psychologically well-equipped spaces. Inspiration for this type of necessary architecture can be drawn from space stations, Arctic and Antarctic research stations, and existing or envisioned moon architecture. But these were mainly the considerations for the first settlement. Hence, urbanists may be confronted with the question of how to develop a Mars city from scratch (as opposed to most major cities on the Earth, which have been growing and changing over centuries) and which criteria are relevant.

For that, it might be desirable to think that many of the things that “went wrong” on Earth, for example, the pollution of the planet through the automobile, heavy industry, and air traffic, can be done better and more environmentally conscious. If such destructions of an overwise “working planet” wants to be avoided, there are various ways to go. Firstly, instead of an anthropocentric view, one may ask what Mars offers, that we can use without necessarily asking the question the other way around – how can human needs (aside from life-maintaining things such as oxygen and nutrition) even be satisfied in this new environment? Based on that, future urbanists may draw inspiration from a small project at Berlin’s river called Holzmarkt. Here, the Berlin-based architectural office Hütten und Paläste designed and developed guidelines (rather than ready-made buildings), within which needs, potentials, and wants of the most cultural future needs could flourish.

Melanie Humann, in a case study of the area, summarises the situation: “In the case of the Holzmarkt, for example, the project initiators had a vision of co-productive urban development which, replacing top-down planning process that negated existing uses and local needs, aimed to secure inclusiveness and integrate goals directed at the common welfare. As such, instead of a three-meter-wide riverside pathway, green and open spaces of width 25 meters were planned to run alongside the riverbank. Instead of office buildings and tower blocks, small-scale structures were designed to provide space for a creative and cultural scene or local tradespeople such as bakers or hairdressers. Larger units would be used as indoor markets, event spaces, or rehearsal rooms for artists […].” Design guidelines and suggestions based on ideals and principles for life on Mars – such as no pollution or destruction of the planet and priority on sustainability – might offer, at least for some spaces such as entertainment, cultural or generally, leisure spaces, a new and exciting approach based on sustainability, equality, and democracy.

The task of the urbanist is to think about such a new settlement not only in terms of a highly technological research station but as a city constructed from scratch. Inspiration can be drawn from Saudi Arabia’s current approach to urban planning.

Acoustic Space

Everyone has their space in the city—everyone, except electric scooters, as we discussed recently. Pedestrians can walk on sidewalks, cars drive on the road, and bicycles on the bicycle lane. But whoever was lying at night in bed, shaken by the noise of a motorcycle driving past, might come to realize a different concept of space: acoustic space. In the book Echo’s Chambers: Architecture and the Idea of Acoustic Space, the author Joseph Clarke states: “In human perception, it is the principal counterpart to optical space, with which it is customarily expected – but occasionally fails – to correspond. It is diffuse and immersive, and as a result, it possesses mysterious and enchanting powers.”

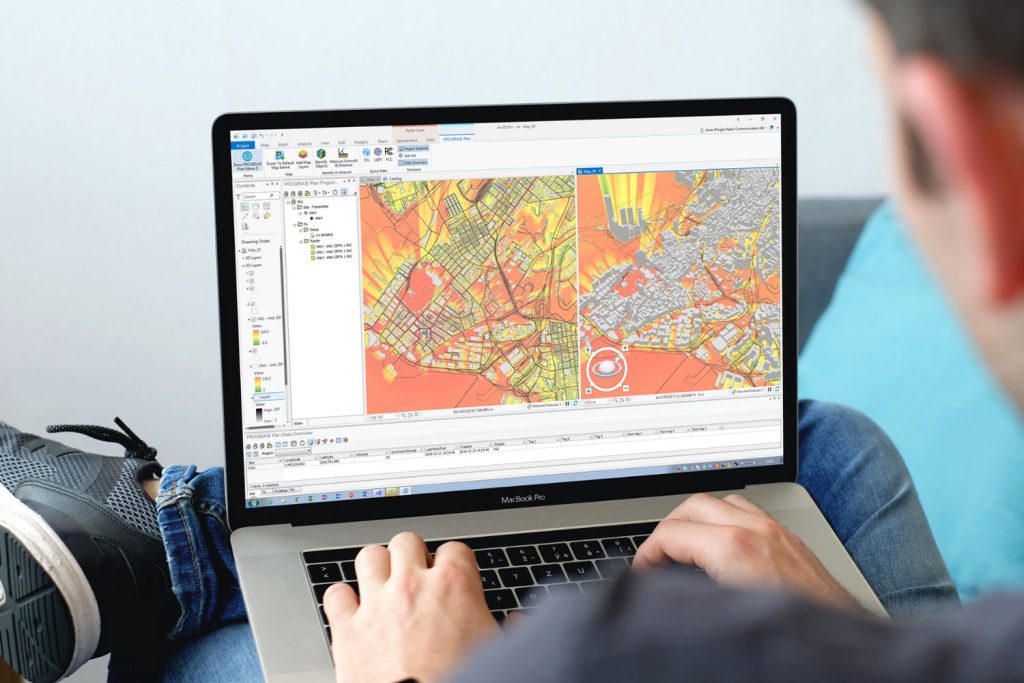

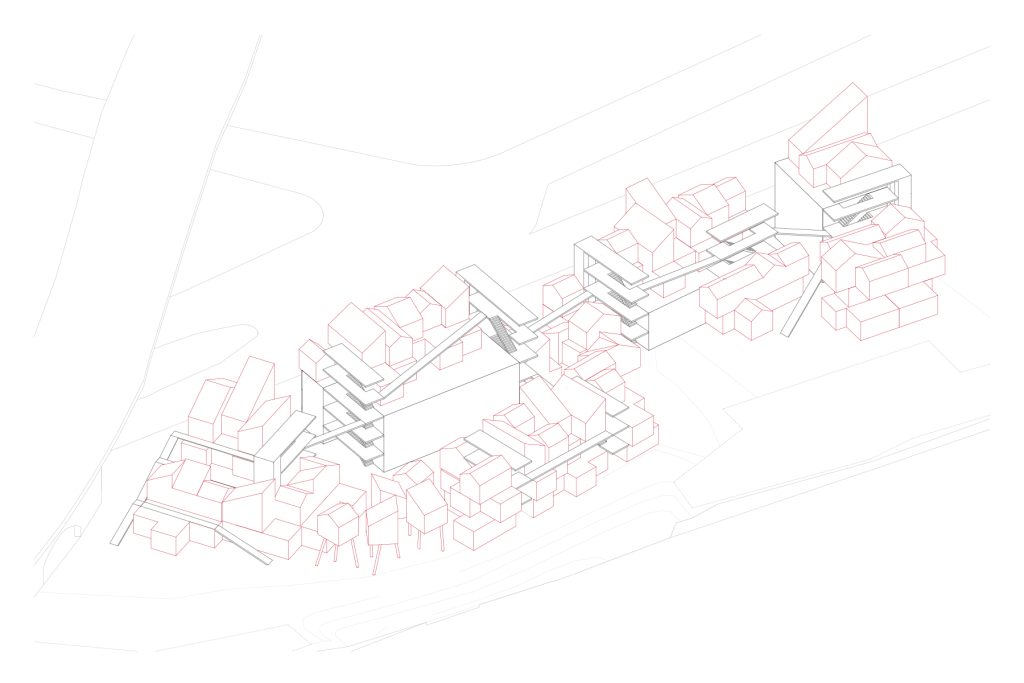

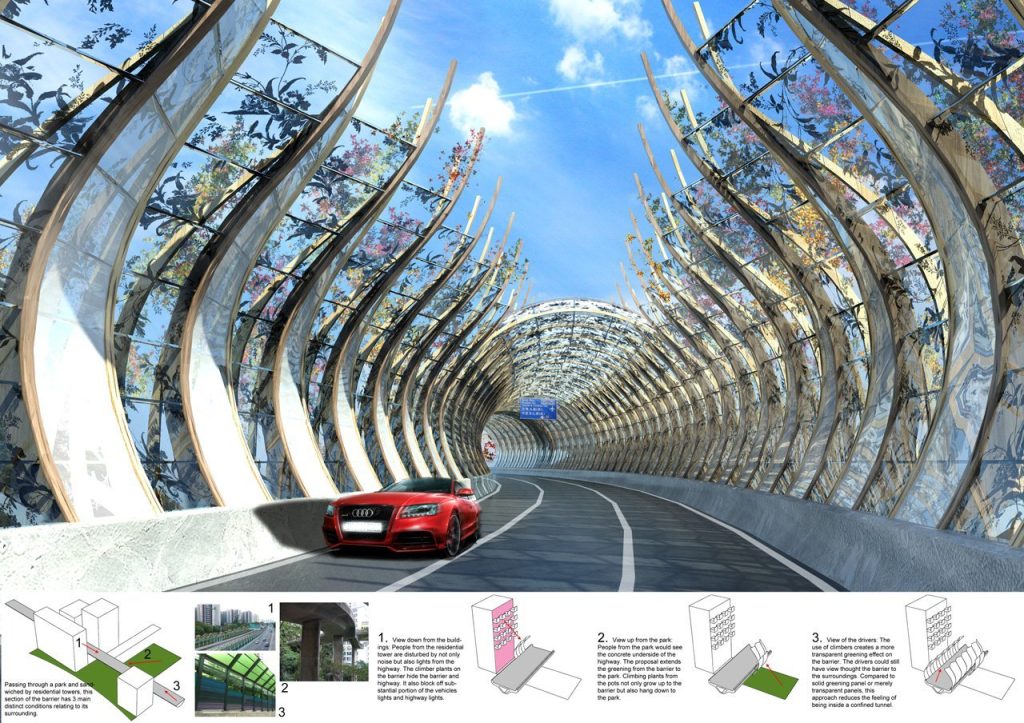

How this looks in detail, can be, for example, read in a paper called “Acoustic Design for Early Stage Urban Planning”. In their case study of an area in Antwerp, the authors suggest: “Based on architectural, economic and mobility boundary conditions, […] a set of building layouts were constructed in consultation with the architects and city planners. […] A line of buildings is used as a noise barrier. In case these are used as dwellings, it is essential that the most exposed façade is well insulated, and that the least exposed façade is sufficiently quiet, in order to secure a fair quality of life for the inhabitants. The interior design could also be optimized, for example, with the entrance along the ‘quiet side’ and noisier rooms such as the kitchen facing the freeway. In any case, strict enforcement of acoustic specifications during construction would be required. Noise maps for road and railway noise were calculated for the different scenarios […].” However, the first awareness of disturbing sound and noise pollution needs to be raised. Hereby, it is noteworthy, that in this understanding of urban space, sound barriers, and walls, as commonly used near highways, are seen as uncreative and perhaps lazy approaches – the opposite of smarter sound design based on research. In some densely populated areas, however, they might be necessary to ensure quality of life. Electric cars, speed bumps, and low-speed zones might further help.

Whether Ukraine’s reconstruction, Mars’ urban planning, or fighting for unpolluted acoustic space, urbanists are confronted with massive challenges, this article aims to support the involvement of urbanists in these areas to ensure a more healthy, supportive, and cooperative planning for the future.