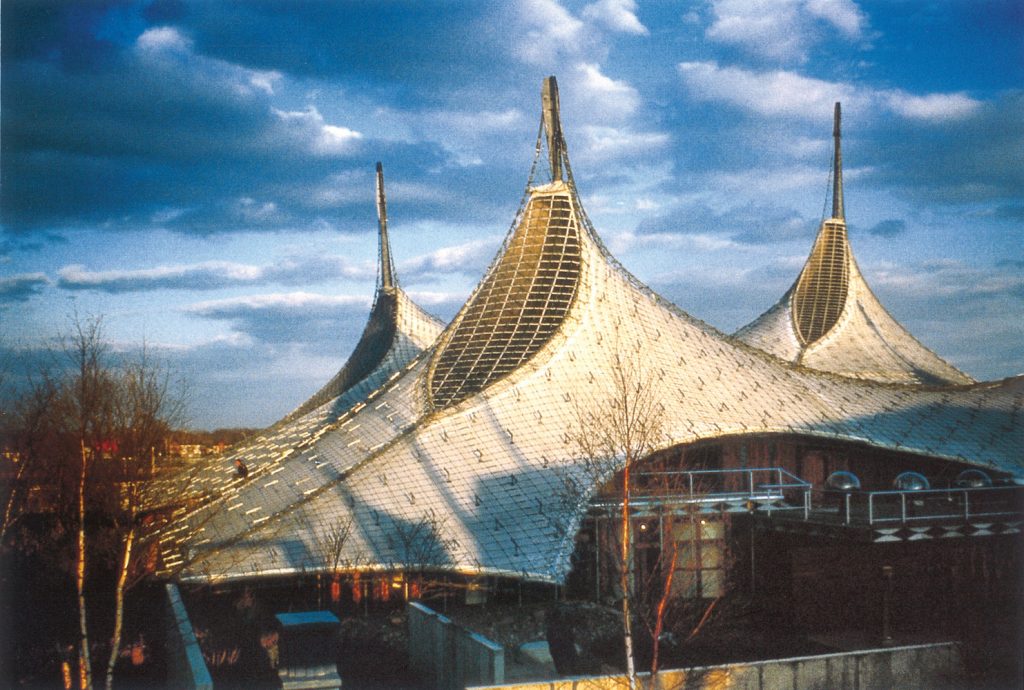

German architect Frei Otto is mainly known for his iconic roof design for the Olympic Park in Munich. Once seen, it is a stadium that cannot be forgotten, so it elegantly swings the roof of steel and acrylic glass around the Western curve of the stadium as well as over the nearby sports hall and swimming pool. Frei Otto designed it together with Günther Behnisch, another influential German architect of the 20th century. Some might also dare to say that this roof – or the German pavilion for the Expo in Montreal in 1967, which Otto did in collaboration with Rolf Gutbrod – is his most relevant work, if not one of the most relevant architectural works of the whole century. However, the architect named Frei, which literally translates to ‘Free,’ arrived at these projects after more than 20 years of experimenting.

“Originally, the pavilion was supposed to remain only during the […] [exposition]. It was allowed to continue standing there but surely one day it will be taken down. Nevertheless, the older it gets, the more anxious I become. I don’t know what I should do: Should I warn the owner that it would be better to tear it down so that I can sleep better?”

Frei Otto in ‘A Conversation with Frei Otto’ by Juan María Songel

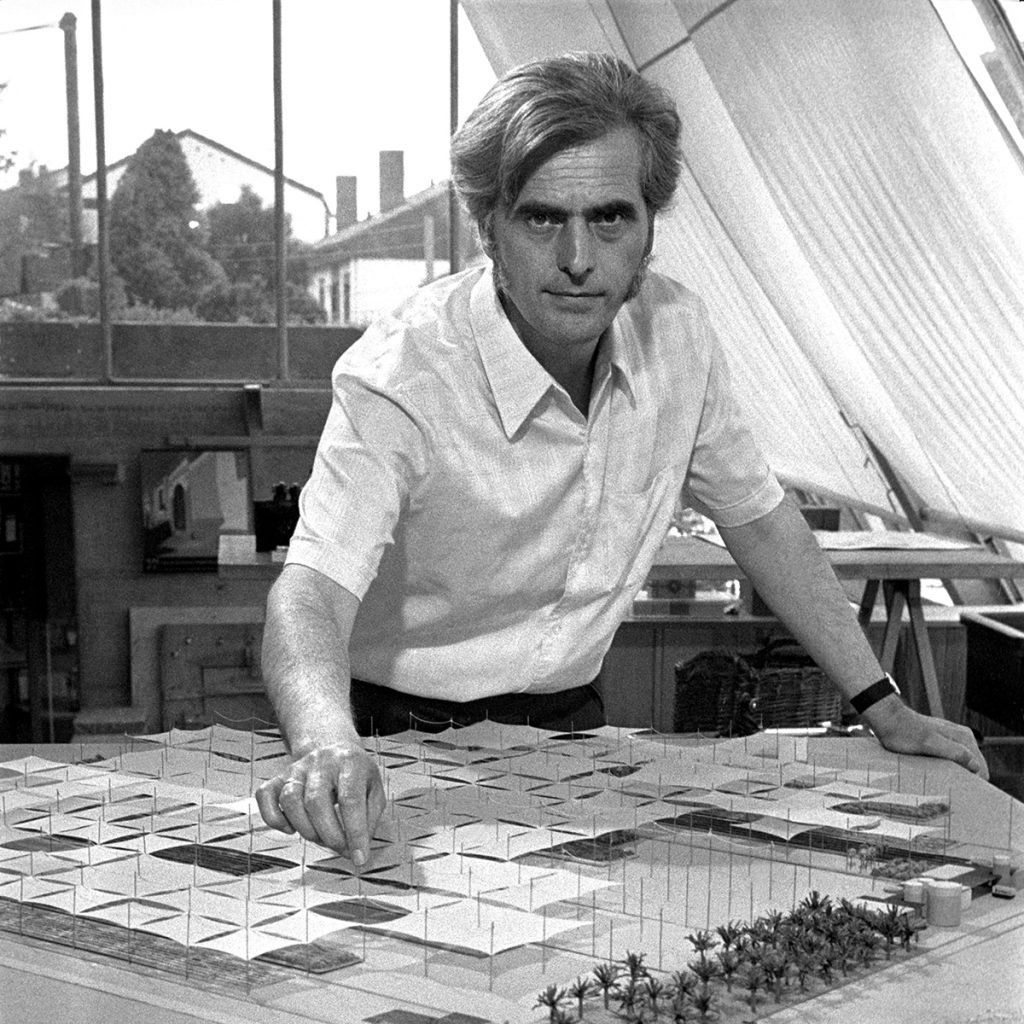

Architecture as Result of Biography

Frei Otto was born in 1925 in the Eastern German town of Chemnitz. His father and grandfather were sculptors, triggering the desire in Otto to follow their career path. Both of his parents were also members of the Deutsche Werkbund (English: German Association of Craftsmen). The Werkbund was an association of artists, architects, and designers that became important in the development of modern architecture and industrial design, particularly in the later creation of the Bauhaus School of Design.

From a young age, Otto started to work as an apprentice in stonemasonry during school holidays. However, a teacher at his school made him interested in gliding and aviation. So much so that after he made a flight license as a teenager, he became increasingly interested in light membranes and materials used in gliding and their behavior against structural forces such as wind. As soon as Otto left the school, he proceeded to matriculate himself to the Technical University of Berlin to study architecture. Nevertheless, his plans did not work out, as he was drafted into the military and consequently trained as a military pilot (and later as a foot soldier).

From 1945 to 1947, he was a prisoner of war in France, and despite his young age and being without a diploma, he became the architect of his labor camp, including having over 200 workers – prisoners of war deployed according to their profession, nevertheless fascinating that the young architect was able to claim and maintain this position. In this position and post-war context, he learned to construct various types of structures with as little material as possible.

1948 Frei finally commenced his studies at the Technical University of Berlin. Here, he manifested his interest in lightweight structures, an interest which 67 years later, shortly before his death, would award him the highest price in architecture, the Pritzker Prize. Their website states: “His architecture [during his studies] would always be a reaction to the heavy, columned buildings constructed for a supposed eternity under the Third Reich in Germany. Otto’s work, in contrast, was lightweight, open to nature, democratic, low-cost, and sometimes even temporary.”

Otto also became one of the first German students to be granted a scholarship to study in the United States, possibly due to his style of architecture, which seemed fitting for the German post-war context as it was different (than before), modern, and light. At this time, the United States was home to many architects, whom Otto came in contact with. To name a few: Frank Lloyd Wright, Erich Mendelsohn, Eero Saarinen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, Walter Gropius. An online biography of Otto states: “In the office of architect Fred Severud in New York, he discovered the model of the Raleigh Arena in North Carolina: a cable net between two large arches, the first suspended roof in architectural history. Mathew Nowitzky, who had designed it, had died in a plane crash shortly before. Frei Otto was so fascinated by the idea that in 1952/53, he wrote his dissertation on the structural engineering of tensile-stressed plane load-bearing structures. By sparingly using highly effective building materials and by exploiting the load-bearing properties of spatial systems, light, movable structures are created,” it says. “Construction shrinks to what is absolutely necessary.”

Own Studio

Throughout the rest of his life, Otto’s own studio became a room for invention, experimentation, and collaboration. In 1952, he started to work as a freelance architect, soon after earning a doctorate of civil engineering and began to “[…] work with ‘the tentmaker’ Peter Stromeyer, [with which] he designed and built three lightweight, minimal temporary structures made of cotton fabric for the Bundesgartenschau (Federal Garden Exhibition) in Kassel, Germany. These were his first works to gain national recognition, in part for how they harmonized with nature”, to the website of the Pritzker Prize.

After these first successes, Otto founded various institutions (for example, the small private ‘Institute for Development of Lightweight Construction’) focusing on lightweight and structural research, and started to teach again (at Washington and Yale University) in the United States. It can be said that the architect, similar to his architecture, was spreading in all directions and let no chance untaken to collaborate with architects, biologists, doctors, paleontologists, philosophers, historians, naturalists, environmentalists, and other scientists, as much as they could give him suggestions and inspiration for his practice. Dieter Wunderlich states on his website: “We are looking for that art of construction that comes into being due to similar processes as the constructions of nature. […] I don’t design; I search. To find the optimal shape for the tent-like roof structures […] – computer simulations did not yet exist – [w]e built wire models and immersed them in soapy water so that they covered themselves with a soapy skin.”

Masterworks

Are current computer programs good enough to prevent the sudden collapses without prior warning?

Frei Otto in ‘A Conversation with Frei Otto’ by Juan María Songel

Otto: My answer is no. This is something that makes me nervous, because not too long ago in Paris […] some shells that had been correctly calculated with computers, had used all of the necessary paraphernalia, and had been checked, suddenly collapsed. The politicians always ask for those responsible, but they can’t blame the engineers in these cases, because they used correctly designed programs according to the theory of elasticity. We ask ourselves why the great master builders of medieval vaults – and Antoni Gaudí as well – were able to build stable structures without having all of the current methods of calculating at their disposal, and why today these mistakes are made even though we have this enormous computational arsenal.

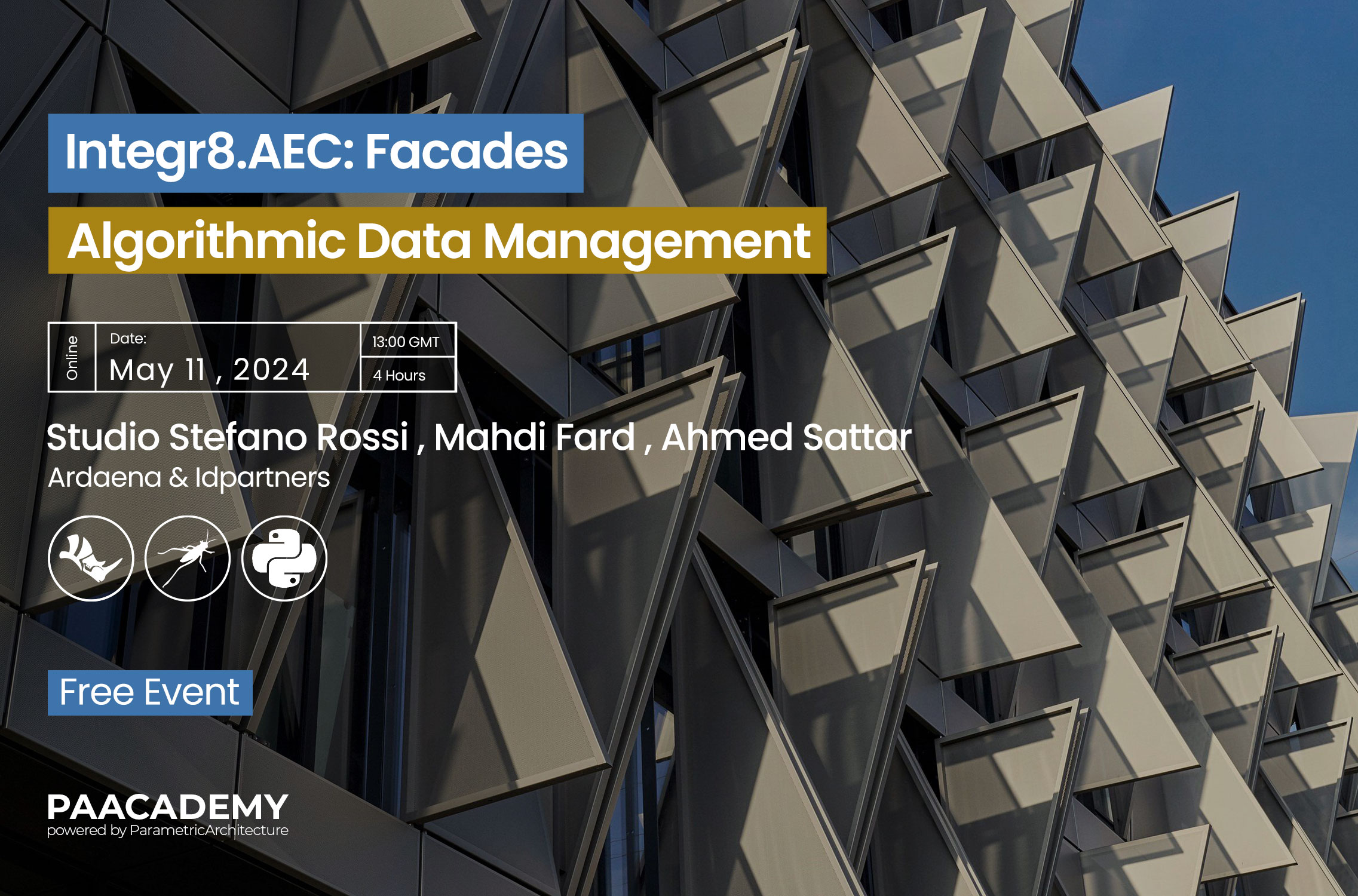

In 1967, Frei Otto became director of the newly founded Institute for Lightweight Structures (Institut für Leichte Flächentragwerke) at the University of Stuttgart. In this capacity, he was commissioned to design the German pavilion at the Expo in Montreal in 1967. He was commissioned because his architecture seemed to (in the eyes of the committee) reflect German industrial craftsmanship and technology the best and clearest. This pavilion, designed together with architect Rolf Gutbrod and engineer Fritz Leonhardt was his main international breakthrough and he found himself somewhat between the two disciplines of architecture and engineering. In the book A Conversation with Frei Otto, he states: “I place myself both on the side of the engineers and the side of the architects; for me, there is no separation. All possible separation is erroneous because experimental physics is as necessary as theoretical physics; it’s not about separating but about integrating.” The next year, he was commissioned to design the Olympic Park in Munich for the 1972 Summer Olympics.

The complicated structure of steel cables of the Olympic Park in Munich was almost not constructed. The company Plexiglas, which made the acrylic glass panels for the roof, states on its website: “One requirement [(in the tender)] was that the roof of the Olympic Stadium had to be transparent. After all, the organizers of the Olympic Games wanted to broadcast the event on color television, which had just been launched at the time and required as much light as possible. A wooden or concrete construction was, therefore, out of the question. […] However, the design […] was dismissed by the jury at first as the idea seemed too risky and unfeasible. After a long selection process and the intervention of one of the jury members, Behnisch & Partner was finally awarded the contract. The model won over the jury with the landscape architecture around the stadium in addition to the extraordinary tent-like roof.”

To ensure structural integrity, the masts support the main cables transmit loads to the strong hand, and do so in an inclined manner. The junction between the various cables that make up the structural mesh is materialized by a knot of steel casting with a system using bolted anchors and tension. The textile cover designed by Frei Otto occupies 74.800 square meters, of which 33,750 square meters are the Olympic Stadium, with a length of 450m.”

Later Career

“The most stable construction is the one that doesn’t exist or has already collapsed. I always said to my students that a collapsed building is the most stable; the standing building has a degree of instability. The question is to know what magnitude exterior actions must have to make it collapse. In principle, every building is unstable; all architecture tries to do is to temporarily make stable what in principle is unstable.”

Frei Otto in ‘A Conversation with Frei Otto’ by Juan María Songel

Frei Otto’s career was devoted to research, experimentation, and publishing – he wrote over ten books on various types of construction approaches and structures. After the Munich Olympic Park, Otto continued to work as an architect, however, with only a few (less than ten) selected projects, amongst them the Convention Center in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in 1974 and the Multihalle in Mannheim, Germany, in 1975. His final work was a collaboration for the roof of the Japanese Pavilion of the German Expo in 2000, which he designed together with Shigeru Ban, who 14 years later would receive the Pritzker Prize just one year before Otto. Throughout the years, Otto continued to share his knowledge through exhibitions, interviews and teachings, and in 2015, a few days after being announced as the Pritzker Prize winner and after having won every possible major award in architecture, he passed away.