As designers, we often find ourselves challenged with measurement questions, with one of the most distinguishable being: how do we determine the success of a design beyond its visual appeal?

Within such a pursuit lies a core principle that transcends all others: universality. In this picture, universal design (which stands at its very essence), also known as “inclusive design,” aims to give all users a seamless experience while respecting their diverse abilities and limitations. Standing out as a design philosophy that leaves no room for discrimination, it strives to create environments, services, and products that are accessible to everyone, regardless of their background or circumstances.

Developed in 1997 by the founder of the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University, an American architect with a physical disability diagnosed at an early age – Ron Mace – this ideology recognizes the diversity of human capabilities and seeks to eliminate barriers that prevent people from fully participating in society, highlighting the 3 essential constituents universal design follows: inclusivity, equity, and empowerment.

For designers, the concept implies being challenged to broaden their perspective beyond conventional norms and consider the full spectrum of human experience, as every user deserves equitable access and usability within the context of present-day built environments.

Nonetheless, despite all the worldwide recognition universal design has received, the reality persists: many cities are still pushing forward infrastructural designs that are fit for only one type of users – people with no disabilities and limitations, neglecting the diverse needs of their inhabitants. In addition to such context, Lowenkron’s striking statistic serves as a poignant reminder: over one billion people worldwide live with disabilities that could interfere with their access to buildings and infrastructure.

That could be argued to be heavily influenced by the fact that the path to achieving truly inclusive environments is filled with challenges. Maintaining quality and making sure that design corresponds to universal design principles requires continuous supervision. Consequently, the following questions arise: who bears the responsibility of oversight? And how can compromise be found between regulatory compliance and practical implementation?

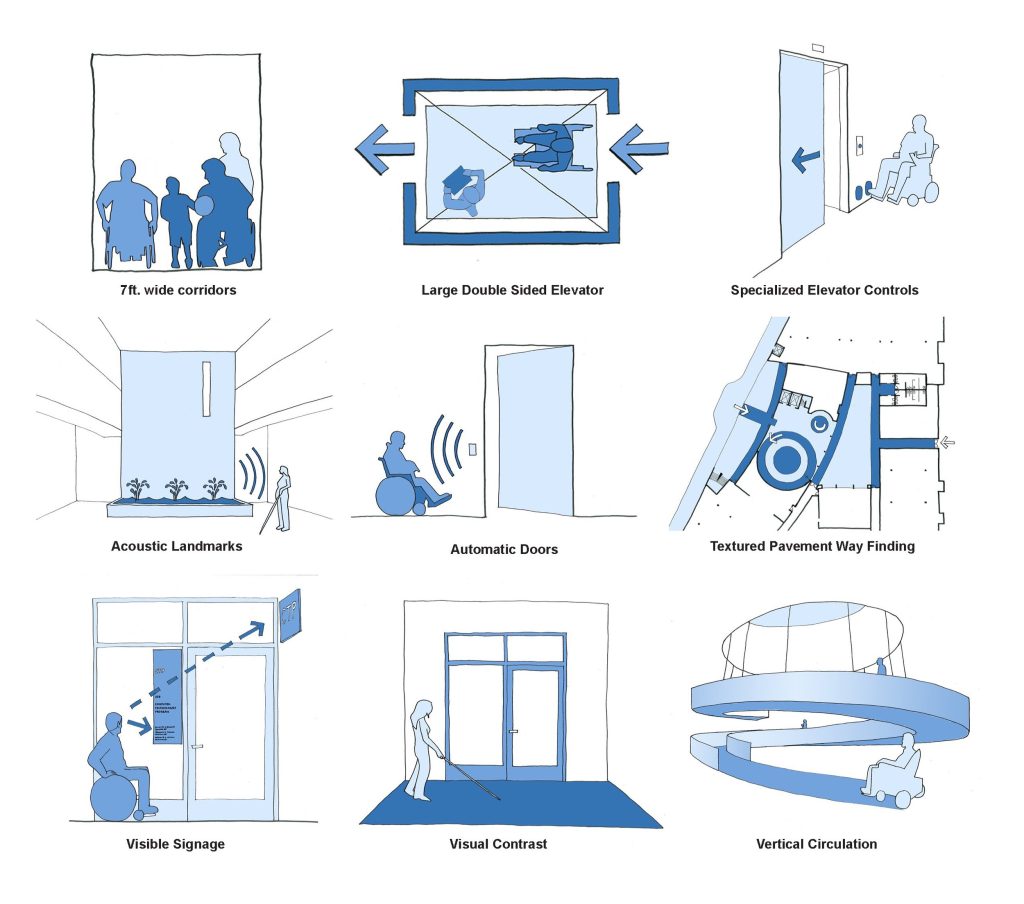

De Souza and De Oliveira’s critique sheds light on the discrepancies that exist in current practices, explaining the occurring dissonance on an example of how cities are still only focusing on small details rather that preparing strategies and planning on larger scale. Besides, even though elements like ramps, elevators, and tactile floors are mandated by law, their improper execution often results in inadequate accessibility. And the lack of preparedness among safety technicians further exacerbates these issues, creating a disconnect between regulatory enforcement and real-world implementation.

On the other hand, even in case a ‘functioning supervision’ (mentioned in the earlier paragraphs) exists, evaluating a design’s inclusivity poses a yet another dispute. However, in universal design, as within any specialty, certain principles serve as guidelines, leading in the navigation of key points necessary for achieving at least partial fulfillment of its goals.

With that being said, the 7 principles formulated initially by a team of architects, product designers, and engineers at North Carolina State University’s Center for Universal Design, prioritize inclusivity by ensuring that designs are equitable (1), flexible (2), intuitive (3), and perceptible (4) to users of all abilities. They aim to minimize physical effort (6), tolerate errors (5), and provide adequate size and space (7) for approach and use, ultimately creating solutions that are accessible and usable by everyone, regardless of their age, disability, or other characteristics.

Both the stated challenges as well as the principles that can help navigate and evaluate the decision-making processes highlight the importance of awareness and advocacy about the transformative power of design, especially within the context of universality and inclusivity. The design has the potential to pave the way for a more equitable and healthy future, as it possesses an exclusive ability to open doors—both metaphorically and literally—to new possibilities for all individuals, irrespective of their abilities or limitations.

As we navigate the complexities of urbanization, universal design remains an indispensable tool for creating environments that truly leave no one behind as it surpasses the traditional boundaries of architecture and design and penetrates into a wide range of disciplines like IT, education, healthcare, transportation, urban planning, product design, as well as digital design.

Returning to the idea of awareness on smaller scale, product design plays an essential role in coming one step closer to approaching the necessary inclusive environments. However, the truth has it even the simplest objects that might appear to an ordinary eye as ‘well-designed’ often prove to be exclusive or challenging for individuals with different abilities. As highlighted in the article “Building a Business Case for Universal Design,” standard design elements such as keyboards and web browsers can pose significant barriers for people with limited arm mobility or those reliant on assistive technologies.

Let us consider an object as humble as a door handle. While seemingly mundane, its design can either facilitate or impede accessibility for various users. Mishra’s example underscores this point eloquently. Positioned at a fixed height, door handles may not cater adequately to individuals of different statures or those with mobility impairments. However, the implementation of automatic gates eliminates such barriers, offering a universally accessible solution that benefits all users.

Furthermore, it seems that addressing “extreme” case scenarios in design often yields unexpected benefits for broader audiences. For example, the sloped sidewalks, intended to assist wheelchair users, inadvertently enhance the experience for far more inhabitants like parents with strollers, individuals with hand-trucks, and many others. Hence, by prioritizing universality in design, we not only remove barriers for specific user groups but also enhance the overall user experience for everyone.

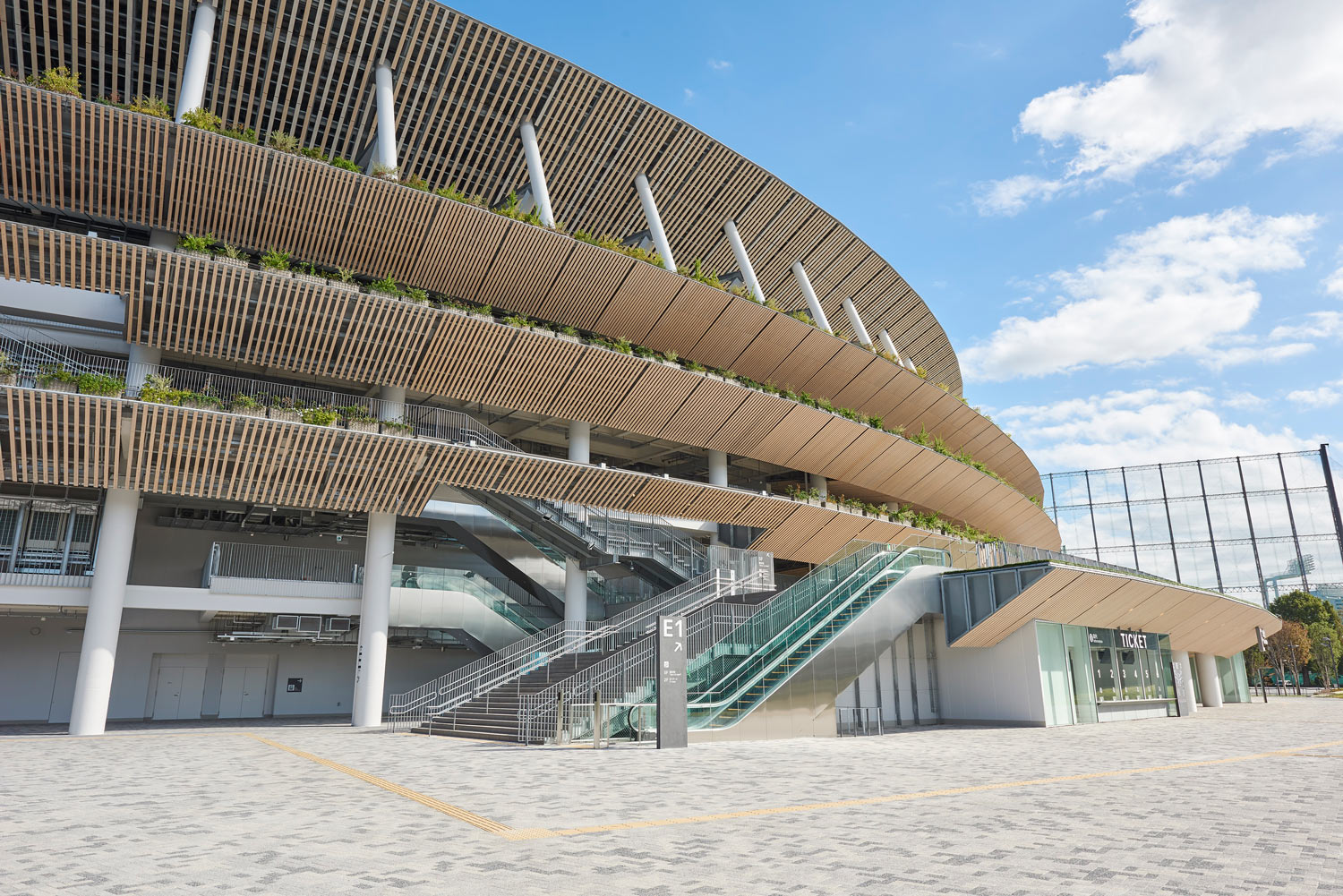

Proceeding further with the investigations on practical applications of universal design in the different disciplines, Japan’s National Stadium in Tokyo, envisioned by a distinguished designer, Kengo Kuma, for the 2020 Summer Olympics, serves as an excellent example of a renowned architectural achievement. Crafted with wood from all 47 of Japan’s prefectures and inspired with Kuma’s traditional yet softer design language, the stadium reflects a commitment to inclusivity and accessibility.

Featuring tailored bathrooms for individuals with mobility, sight, and hearing impairments, wheelchair-accessible seating with unobstructed views, elevators with custom-made car operation panel and buttons with raised characters, handrails on vertical passages, three-layer stands for reduction of vertical travel distance by foot, various circulation routes, nursing rooms, and stroller spaces, the stadium sets new benchmarks for universal design in Japan. And despite the fact that the pandemic’s closure of the Games to spectators has limited the utilization of these features, experts anticipate their lasting impact.

Last but not least, universality should be present not only when it comes to interacting with physical objects and environments but also the ones found within the scope of digital realms. Speaking of such, Amazon, with its vision to become Earth’s most customer-centric company, exemplifies this commitment by prioritizing accessibility in its website design. According to Accessibility and Assistive Technology, it is achieved through utilization of web language designed specifically for vision impairment, hearing loss, mobility limitations, features for learning, speech disabilities and step-by-step guidance. Together with outstanding web design, Amazon’s dedication to the goal is translated through a range of devices. For example, Echo devices (powered by the Alexa voice assistant) that offer hands-free access to various services (benefiting individuals with mobility or dexterity impairments), Kindle e-readers and the Kindle app that include features such as adjustable font sizes and screen magnification (enhancing accessibility for users with visual impairments).

In conclusion, universal design, being an integral part of modern architecture and design, has forever changed the approach towards the design decision-making. It taught professionals to strive for creation of accessible, functional, and aesthetically pleasing spaces for all. With ‘all’ being the keyword in the previous sentence, it showcased to us that universality in design should not be a privilege but rather a necessity. As Michael Nesmith (Accessibility designer of Amazon) cleverly notes, everyone experiences limitations at some point in life. Thus, raising the standards of universal design integration is crucial in shaping inclusive environments where diversity is celebrated, and accessibility is not just a goal but a fundamental principle guiding decision-making in city and space design.