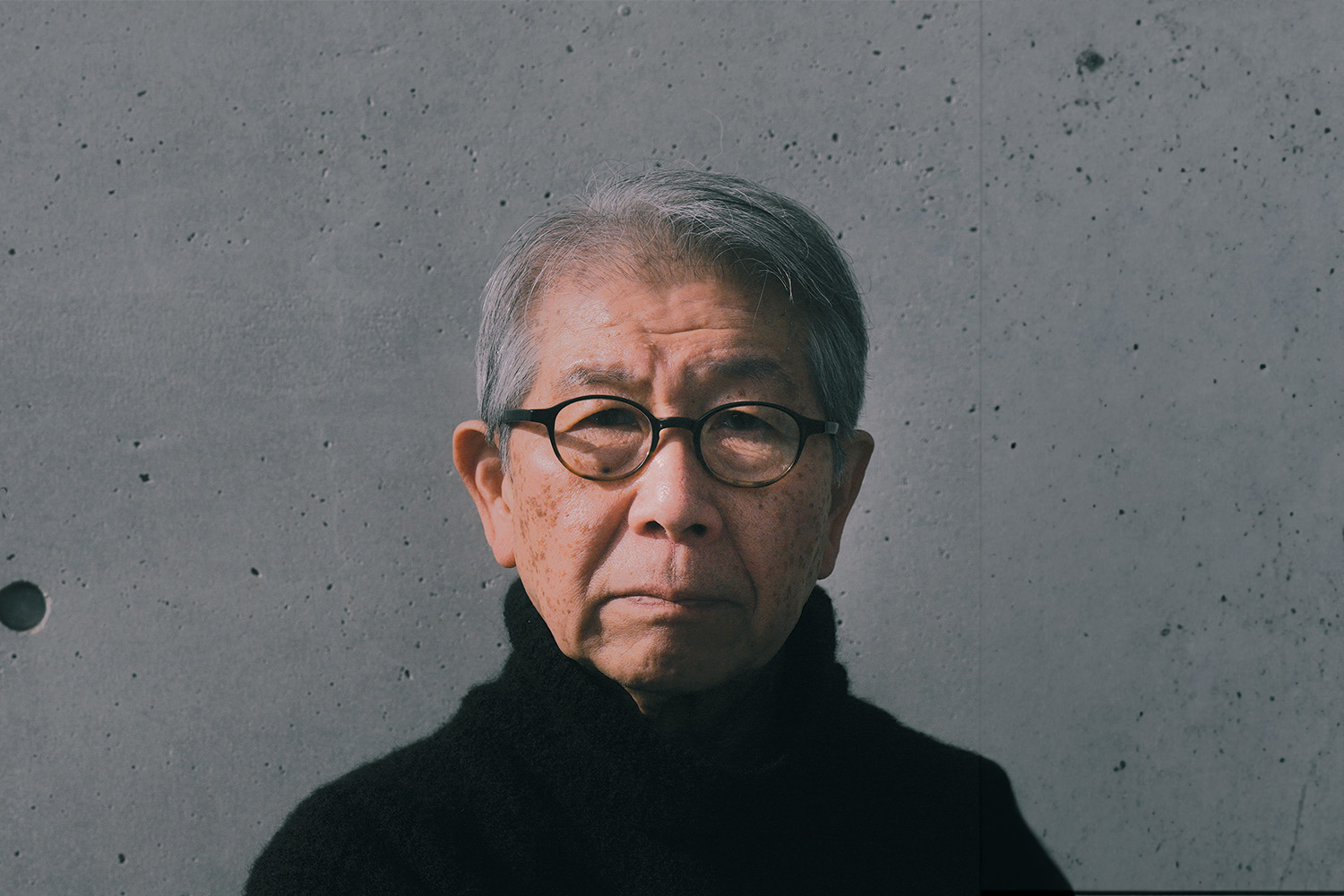

Riken Yamamoto, architect and social advocate from Yokohama, Japan, received the 2024 Pritzker Architecture Prize!

He is the 53rd Pritzker Architecture Prize laureate and the ninth from Japan. Yamamoto is known for creating kinship between public and private realms, inspiring harmonious societies despite diverse identities, economies, politics, infrastructures, and housing systems.

Riken Yamamoto was born in Beijing, Republic of China, in 1945 and relocated to Yokohama, Japan, shortly after the end of World War II. When he was 17, he visited the Kôfuku-ji Temple in Nara, Japan, and was captivated by the Buddhist elements. This experience was his first influence. In his words, “It was very dark, but I could see the wooden tower illuminated by the light of the moon, and what I found at that moment was my first experience with architecture.”

He graduated from Nihon University’s Department of Architecture, College of Science and Technology in 1968. He received a Master of Arts in Architecture from Tokyo University of the Arts, Faculty of Architecture, in 1971. Later, he founded his studio, Riken Yamamoto & Field Shop, in 1973.

He expresses that the value of privacy has become an urban sensibility and emphasizes upholding community life. He defines community as a “sense of sharing one space,” challenging conventional ideas about freedom and privacy while opposing longstanding practices that have turned housing into a mere commodity, detached from any meaningful connection with neighbors.

“For me, to recognize space is to recognize an entire community,” Yamamoto states. “The current architectural approach emphasizes privacy, negating the necessity of societal relationships. However, we can still honor the freedom of each individual while living together in architectural space as a republic, fostering harmony across cultures and phases of life.”

The 2024 Jury Citation states, “for creating awareness in the community in what is the responsibility of the social demand, for questioning the discipline of architecture to calibrate each architectural response, and above all for reminding us that in architecture, as in democracy, spaces must be created by the resolve of the people…”

Tom Pritzker, Chair of the Hyatt Foundation, says, “Yamamoto develops a new architectural language that doesn’t merely create spaces for families to live, but creates communities for families to live together… His works are always connected to society, cultivating generosity in spirit and honoring the human moment.”

Alejandro Aravena, Jury Chair and 2016 Pritzker Prize winner, says, “One of the things we need most in the future of cities is to create conditions through architecture that multiply the opportunities for people to come together and interact. By carefully blurring the boundary between public and private, Yamamoto contributes positively beyond the brief to enable community; he is a reassuring architect who brings dignity to everyday life. Normality becomes extraordinary. Calmness leads to splendor.”

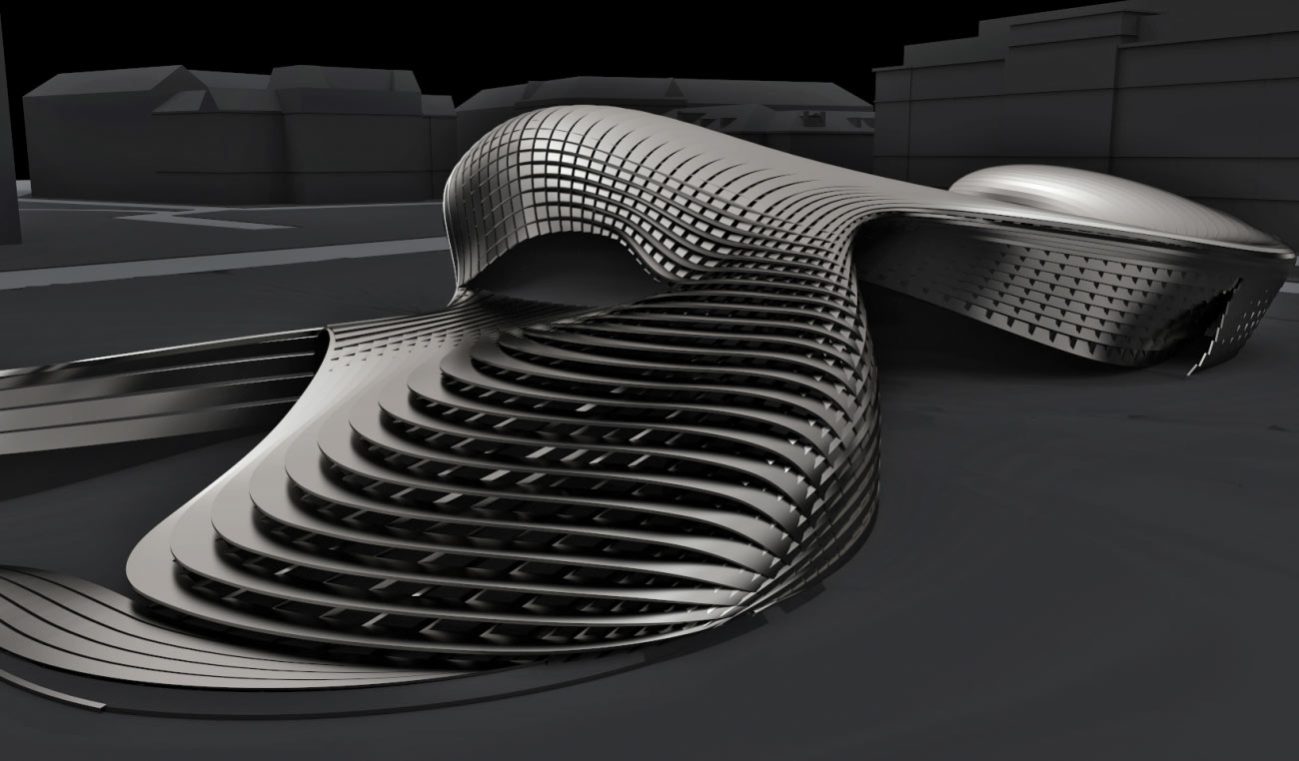

Yokosuka Museum of Art, Yokosuka, Japan (2006)

Riken Yamamoto’s studio was chosen to plan a museum through a Quality Based Selection in 2002, which was the first trial run by the city of Yokosuka as a Japanese municipality. The design of the project started from scratch and was continued through collaborations with various people, including museum curators.

The project was situated in Yokosuka, surrounded by mountains and facing the sea to the north, with its design influenced by the typical valley topography of the area. Most of the architectural volume was buried in the ground to create a museum that blended with the natural landscape. The double-skin roof and wall, consisting of glass plate outside and iron board inside, is shown from the exterior. This part covers the areas for exhibition and collection. The edge of the interior space includes publicly open facilities such as restaurants and workshop rooms.

Ecoms House, Tosu City, Japan (2004)

Ecoms House is a prototype residence for SUS Corporation, manufacturing aluminum precision machine parts and furniture. This project was initially an experiment to create something out of aluminum that could not be expressed with steel. It was constructed out of aluminum panels portraying 24-foot by 24-foot boxes. The traditional tatami mats used in Japanese homes inspired the exterior of the building, with each of the four sides consisting of transparent, opaque, and glass-covered aluminum lattice panels.

Fussa City Hall, Tokyo, Japan (2008)

Fussa City Hall is situated in a densely populated residential area about 50 km away from Tokyo city center. The building’s design is in harmony with the local topography, with low hills ascending from the banks of the Tama River. The lower levels, known as the “Forum,” are open to the public and utilized by the citizens. They are placed beneath an undulating organic roof, from which two twin towers emerge. The roof itself is a green public space for citizens, serving as a site for various events and activities. The greenery on the roof enhances the building’s energy efficiency, reducing energy losses and helping to integrate it into the surrounding environment.

The two tower that has an iconic image in the city features the main offices for the city hall. To ensure the best possible use of space within the offices, the main idea is to position the building’s structure on the exterior facade. This design approach eliminates the need for structural elements within the working space, maximizing the available floor area. The outer skin structure features pillars and beams that become progressively thinner towards the top of the tower, creating a light and graceful appearance. The slab and outer skin structure are constructed using factory-made, pre-cast concrete.

Jian Wai Soho, Beijing, China (2004)

The Chaoyang district, located four kilometers to the east of Beijing’s center and in close proximity to China’s World Trade Center, has been chosen as the site for a 700,000-square-meter complex of high-rise buildings. This complex promotes a new urban model that mixes residential and workspace areas. Eleven of the twenty towers planned for the SOHO project are located in this area, along with four small five-story buildings that are designed as ‘villas’. Instead of aligning with the street grid, the square floor plan of all the buildings rotates 25º with respect to the north-south axis, maintaining an ideal angle to bring sunlight to each tower.

Each apartment tower is designed to cater to different needs. Some units have a small, easily accessible workspace at the entrance, while others are centered around a multipurpose distribution space known as an ‘atelier.’ Finally, there are units in which the entire space is reduced to a single room that can be further divided using mobile partition walls. These volumes are joined by small pedestrian footbridges and have small rooftop gardens that are accessible from the dwellings on the same level.

Hotakubo Housing, Kumamoto, Japan (1991)

Riken Yamamoto asked the initial question and the great deal of thought for the project began: How might these units accommodating 110 entirely different families be conceived as a community? The final outcome was an arrangement of buildings that were organized around a central open space. The design of the space was based on the idea of a threshold wherein the central open space couldn’t be accessed directly, but only through the units which served as gates to the central open space.

Saitama Prefectural University, Koshigaya, Japan (1999)

This project was for a university that specializes in nursing and welfare. The studio was inspired by the education system of the university whose aim is to nurture and develop talented individuals who can take on leading roles in their local communities that require mutual cooperation. To achieve this, the studio designed an architectural model that breaks free from the conventional faculty and department framework, rather than completing or closing each department they proposed one single volume.

The plan started with one volume, and there were several issues that needed to be addressed for each specific area. However, the solution was designed in a way that each element of the architecture was correlated and made the whole structure seem clear and systematic. Consequently, the architecture appeared as if it were the landscape, and the foundation of the city seemed to be part of the architecture.