The evolution of architectural drawings spans thousands of years. With the consequences of countless technological advancements, it’s hard to deny how much architectural representation has evolved from pyramid construction instructions on papyrus paper to computer algorithms generating ideal architectural scenarios.

Hand Drawing Era

As impactful as Egyptians are, long before our favorite mummified architects, the earliest form of drawings is found in Saudi Arabia and Jordan. About 9000 years ago, Neolithic humans drew plans called “desert kites,” which are known to be hunting traps made from dry stone walls. They then etched these aerial view plans into massive stone tablets. These etchings are found in locations such as Jibal al-Khashabiyeh in Jordan and Jebel az-Zilliyat in Saudi Arabia. A mere 6000 years ago, many uncovered lost artifacts and destroyed civilizations later.

The era of hand drawing continued to prove itself through many material forms, including papyrus paper, wax tablets, and parchment paper. The first architectural drawing on papyrus paper was the Plan of the Tomb of Amenemhet II in 1800 BC, which provided a detailed layout of the royal tomb complex. After all, the Egyptians believed the most significant thing you could do in your life was die. I digress.

Hand-drawn architectural drawings continued to develop significantly during the Middle Ages, and parchment paper was commonly used. The earliest known architectural drawing on parchment paper was the plan of St. Gall Monastery in Switzerland in the 800s, which also includes probably the most stunning library you’ll ever see. Although the plan of St. Gall may not be the absolute earliest example, it is one of the most well-preserved architectural drawings on parchment paper.

Moreover, parchment paper continued to be used for several centuries due to its durability for detailed work, encompassing the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, but it started declining after the increasing usage of paper. The first example of an architectural drawing on paper that was printed and widely distributed was Sebastian Serlio’s Tutte l’opere d’architettura et prospective, published in 1537.

As printing became significantly popular in the Renaissance, examples such as Andrea Palladio’s Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, Leon Battista Alberti’s De re aedificatoria, and Michelangelo’s architectural drawings became widely distributed as well. Before we fall victim to the bubonic plague, let’s conclude the hand-drawing era and acknowledge that we have come a long way in setting the foundations of representing architectural concepts in tangible contexts, from early stone tablets to printed architectural manuscripts.

Pre-CAD

Hand drawing became more standardized when Alois Senefelder invented lithography 1796 before the Industrial Revolution. In lithography, artists draw with greasy materials on a stone, chemically treat it to separate the water from the ink, apply ink again to the whole of the stone, and then press the paper onto it, attracting the inks with each other to create detailed prints.

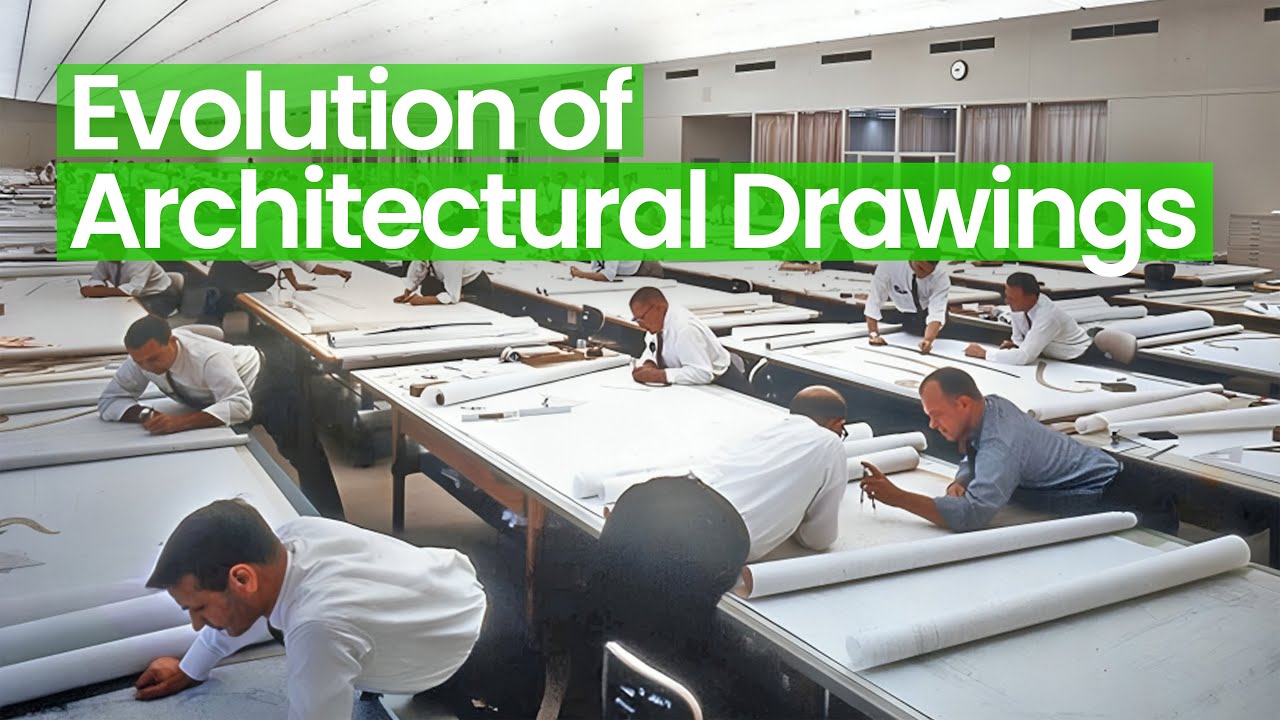

Notable architectural lithographies from the 19th century include Sir John Soane’s Architectural Studies, the drawings of Ecole des Beaux-arts, and Pierre Chabat’s Normandy Villas. Considering the amount of labor that went into creating these masterpieces, they definitely deserve admiration. Moving forward, the pre-CAD era continued to expand in the 20th century with materials such as graphs, tracing, blueprint paper, mylar, and vellum.

The biggest difference between the pre-CAD and post-CAD era is that architects used tools like drawing boards, pencils, erasers, and T-squares instead of computers. However, this also meant that there was no margin for error and no chance of returning after the drawing was put on paper, and it probably also destroyed the poor architects’ postures. So in other words, not a lot has changed since then, well, at least not until CAD arrived.

Post-CAD

The revolutionary context of CAD (aka computer-aided design) changed the game. In 1961, Dr. Patrick Hanratty, regarded as the “Father of CAD,” developed the software DAC (Design Automated by Computer) under General Motor Research Laboratories. DAC was the first CAD system to use interactive graphics and was useful in the auto industry for designing molds.

Still, sadly, the company discarded the system because of its obsoleteness. Hanratty claims that today, 70 percent of all 3-D CAD systems trace their roots back to his original code. Hats off to Hanratty. Later, in 1963, Ivan Sutherland was busy developing Sketchpad, the first-ever graphic user interface with an X-Y pointer display, which allowed users to draw objects.

Sketchpad is still considered a significant breakthrough in creating computer graphics and the interaction between humans and computers. Moving on, the evolution of CAD continued with programs such as CADD by aerospace manufacturing corporation McDonnell Douglas, PDGS, an internally developed CAD system by Ford, and Digigraphics by ITEK (which was a system sold for the low price of $500,000). Breaking free from the boring norms of 2 dimensional systems, in 1972, Synthavision was developed by MAGI.

While technically not a CAD program, it was recognized as one of the earliest 3D visualization programs, creating complex 3D visual effects and animations for movies such as Star Trek and Tron. At this point, if you thought we were done with our Father Hanratty, you are wrong.

In 1974, ADAM was released by Hanratty. It was one of the first systems to incorporate actual 3D solid modeling techniques, was open to work on every machine, and %80 of CAD programs can be traced back to it. This time, for real. More and the CAD ecosystem developed itself by the late 70s with programs like CADAM (used for aerospace and defense industries), Unigraphics by Siemens (which offered robust parametric design capabilities), and MiniCAD, which was the best-selling CAD software for Mac computers of the time. Finally, the moment we have all been waiting for, AutoCAD was released in 1982 by Autodesk. It became and still is one of the most widely used CAD programs, setting the standard for CAD software and offering low-cost accessibility for a broad range of users.

The era post-AutoCAD offers many more programs, such as Pro/Engineer, Solidworks 95, CATIA, and more. Later, in 1996, 3D Studio Max was released by Autodesk, which was and still is widely used for modeling and animation, and finally, Rhino, which was released in 1998 by Robert McNeel & Associates. Rhino introduced NURBS modeling tools that were significant for complex computational design tasks and, to this day, protects its relevance in the industry. Other important software include Revit, which was released by Autodesk in 2000 and is one of the most widely used BIM software supporting parametric design. The list goes on, but for the sake of this video, let’s take a look at our next era.

AI Integration

Love it or hate it, AI is here and here to stay. In recent years, AI has significantly impacted architectural practices. Yet its integration into these practices did not happen overnight. We can’t start explaining the impact of AI in architecture without mentioning one of the most significant generative design tools, Grasshopper for Rhino, released in 2007.

Although not an AI tool, Grasshopper set the basis for generative design. The plugin allowed for parametric design capabilities and profoundly influenced architectural design. The integration of AI into the industry became more widely available after the late 2010s, with tools including Finch, Maket, Midjourney, and more. But at this point, the advancement of architectural drawings has progressed so much that it has become a controversial topic. As beneficial as AI can be, it is inevitably inclined to be repetitive and inaccurate. A big question mark here is what happens when the creation process of such a human-centered creative field is left in the hands of computer-generated algorithms. AI will never stop evolving, just like humans, yet its consequences in the context of architectural drawings seem to be positive… so far.

Read more on the evolution of architectural practice: From hand drawings to computer-aided design to AI integration.

Leave a comment