Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer was born on March 19, 1905, in Mannheim, Germany, to a wealthy middle-class family. Speer, whose father and grandfather were architects, began his architectural education at the University of Karlsruhe in 1923. When the economic crisis ended, he first transferred to the Technical University of Munich, then to the Technical University of Berlin in 1925, where he became a student of Heinrich Tessenow.

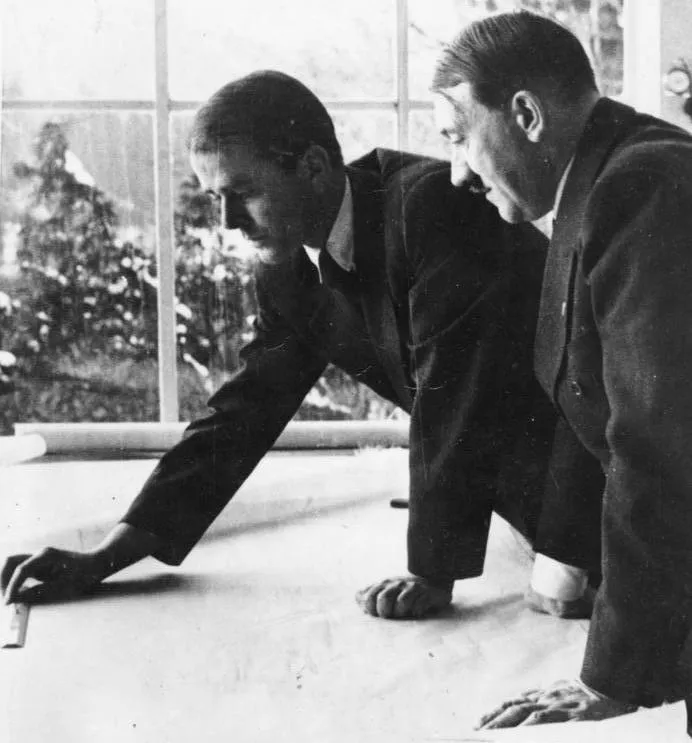

Speer, who joined the Nazi Party in 1931, caught the attention of Adolf Hitler and quickly became one of the party’s most important architects. After Paul Troost’s death in 1934, he was appointed chief architect of the Nazi Party. He took part in many important projects, from the design of the Party Congress grounds in Nuremberg to the reconstruction of Berlin. He received the title of professor in 1937 and became the construction manager of Germany’s new Chancellery Building in 1938-1939.

Speer’s Architectural Career and His Connection to Nazi Germany

Albert Speer’s architectural career was shaped by the influence of Nazi ideology and propaganda. His professional life, which began with modernist tendencies, evolved into a different direction with Hitler’s special interest in art and architecture. Hitler’s dream of turning Berlin into the “World Capital of Germania” played a key role in Speer’s rise. Speer, who became one of the most important tools of Nazi propaganda, tried to show the regime’s power through architecture by designing large-scale and impressive structures.

The Nuremberg rally grounds were designed for mass ceremonies with giant columns and wide facades, and the physical representation of Nazi ideology was created through these structures. In 1942, with his appointment as Minister of Armaments and War Production, he moved away from architecture and into the management of the war industry, but his architectural role in Nazi Germany and his influence in propaganda activities left an unforgettable legacy.

Nazi Germany used architecture not only as an aesthetic element but also as an ideological and political propaganda tool. Hitler’s perspective, inspired by the Roman Empire, brought monumental and classical architecture to the fore. Massive-scale structures were designed to symbolize the permanence and authority of the Nazi regime.

Nuremberg rally grounds

One of the most prominent examples of this ideology was the Nuremberg rally grounds. One of the most important propagandist architectural projects designed by Albert Speer for the Nazi regime was the Nuremberg Rally Grounds (Reichsparteitagsgelände). This area was built as a huge ceremonial and demonstration stage for the annual party rallies held by the Nazi Party from 1927 onwards.

The complex, which covers an area of 11 square kilometres, was designed to reflect the grandeur and discipline of Nazi ideology. One of the most striking structures of the area was the Luitpoldarena, which could hold 50,000 people, and the Zeppelinfeld, surrounded by a giant grandstand. The Zeppelinfeld Grandstand provided a stage complete with giant floodlights rising into the sky, which Speer called a “cathedral of light” (Lichtdom).

This magnificent light show was used to increase the power of Nazi propaganda at the rallies. Another important structure of the Nuremberg Rally Grounds was the 400,000-seat Congress Hall (Kongresshalle), which was never completed but was inspired by the Colosseum in Rome. Today, the area functions as a history museum examining the architectural and propagandistic effects of the Nazi regime.

Ruin Value

One of the most striking concepts that Albert Speer brought to Nazi architecture was the “Ruin Value” theory. According to this theory, even if the buildings were destroyed centuries later, they should remain standing in an impressive and magnificent way like the Roman and Greek ruins.

Hitler was influenced by ancient Roman and Greek architecture and wanted the Nazi structures to one day remain as historical relics like the works of these civilizations for future generations. This theory proposed by Speer enabled Nazi buildings to be designed as a long-term propaganda tool. Accordingly, more durable stone blocks were preferred instead of modern materials such as steel and concrete.

One of the most important examples of this understanding was the “Volkshalle” (People’s Hall) planned to be built in Berlin. This building, one of the most important structures of Hitler’s plans to transform Berlin into the “World Capital of Germania”, would have a giant dome and should be able to remain an impressive ruin even centuries later.

Germania Project

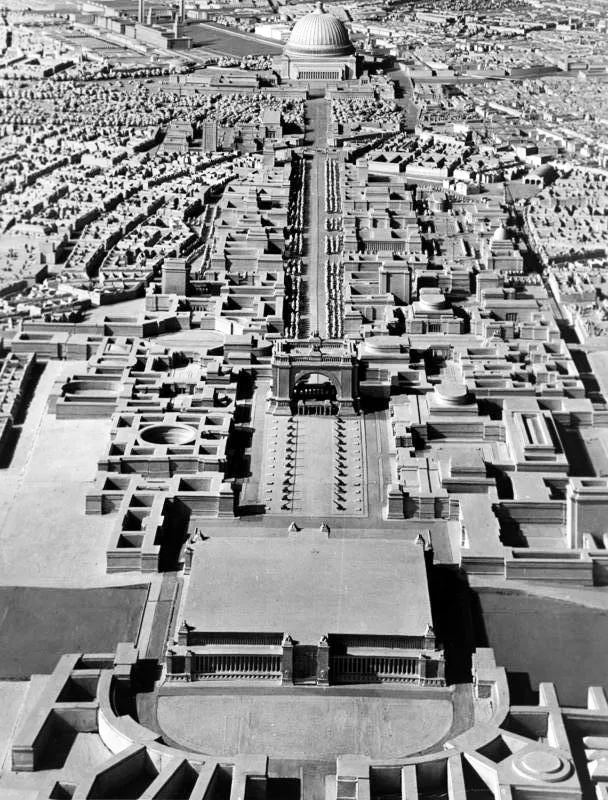

One of Albert Speer’s most ambitious projects was Adolf Hitler’s plan to transform Berlin into the “World Capital of Germania” (Welthauptstadt Germania). This project was a massive urban transformation plan designed to symbolize Nazi Germany’s dominance and ideological superiority over the world. Launched in 1937 under Speer’s leadership, the Germania project aimed to make Berlin the largest and most magnificent capital in Europe.

The urban planning was designed around monumental boulevards, giant structures, and a layout that would reflect the absolute power of the regime. A central element of the project was the grand East-West Boulevard (Ost-West Achse), a 5-kilometer-long main boulevard running north-south. This axis was to be crowned by a magnificent Triumphal Arch, where Hitler planned to hold military parades. However, due to the beginning of the war and the depletion of Germany’s resources, much of the project could not be realized.

One of the most striking structures of the Germania project was the Volkshalle (People’s Hall), one of Hitler’s biggest dreams. Inspired by the Pantheon in Rome, this giant domed structure would be one of the largest indoor spaces built up to that time, with a height of 290 meters and a diameter of 250 meters.

The building’s capacity was planned to accommodate approximately 180,000 people, and it was thought that the sound that would echo inside would increase its effect on the crowd. The main purpose of designing the Volkshalle on a grand scale was to reinforce the power of Nazi ideology and Hitler’s absolute authority through architecture.

On the other hand, the other iconic structure of the Germania project, the Triumphal Arch (Triumphbogen), was a monument that was intended to be built, inspired by Napoleon’s Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Planned to be approximately six times the size of the example in Paris, this structure would house the names of the two million German soldiers who died in World War I and symbolize the military power of Nazi Germany. However, like most of these massive projects, the Triumphal Arch was never completed due to financial and logistical inadequacies.

New Reich Chancellery

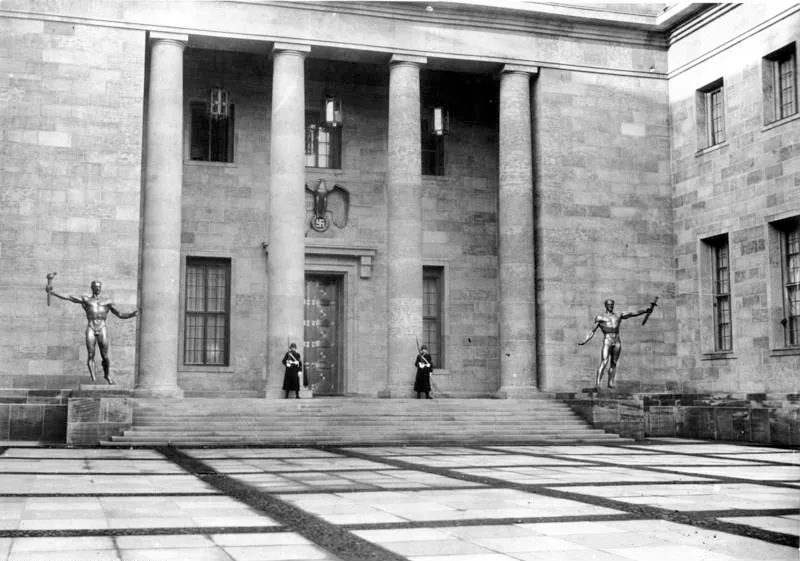

One of Albert Speer’s most prestigious projects was the New Reich Chancellery (Neue Reichskanzlei), built between 1938 and 1939. This building in Berlin was designed as Hitler’s most important administrative center in Germany and was built on an exaggerated scale to reflect the power of the Nazi regime.

Speer completed the Reich Chancellery at an extraordinary pace, in just one year, in line with Hitler’s wishes. The interior design of the building emphasized the authority of the dictatorial regime with long marble corridors, massive doors and magnificent ceremony halls.

The 146-meter-long main entrance hall in particular was designed to ensure that Hitler would make an impressive impression on his guests. One of the most striking sections of the Chancellery building was the large hall where Hitler’s personal office was located; this room was decorated with symbols reflecting Nazi ideology and the cult of leadership.

However, at the end of World War II, the building was subjected to heavy bombardment and was completely demolished by the Soviets after the war. Today, a large part of the area where the building stands has become a section of the Berlin Wall and is now considered a part of social memory.

Albert Speer’s Postwar Career and Legacy

After the war ended, Speer was tried at the Nuremberg Trials. He avoided the death penalty because there was no conclusive evidence that he was directly involved in the genocide decisions, but he was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

In his autobiography, “Inside the Third Reich,” written after his release, he portrayed himself as an architect who admired Hitler’s vision and argued that he had distanced himself from ideological orientations. However, historians agree that Speer was not just a technocrat, but played a key role in managing the war economy and condoned the use of forced labor.

Nazi architecture was designed to reflect the power of the totalitarian regime with a neoclassical and monumental style. This architectural approach, pioneered by Albert Speer, was used as a symbol of authority that emphasized the insignificance of the individual with its gigantic dimensions, symmetrical order and ostentatious magnificence.

This approach brought with it many criticisms in terms of architecture. Speer’s structures were built not only for aesthetic purposes, but also to shape the psychology of the people and make them feel the power of the regime. These designs, disconnected from the human scale, were the product of an understanding that suppressed the individual and sanctified absolute authority. Today, Nazi architecture is considered one of the most extreme examples of ideological propaganda in the history of architecture.

Albert Speer continues to be one of the most controversial figures in the history of architecture. His designs were used as propaganda tools that reflected the ideological power and authority of the Nazi regime, revealing that architecture could be not only an aesthetic but also a political tool.

Today, the legacy of Nazi architecture is preserved as a historical warning to remind us of the mistakes of the past. Speer’s understanding of urbanism, with its wide boulevards and monumental structures, bears similarities to Stalinist architecture in the Soviet Union and urban planning in Fascist Italy. However, contemporary architecture has moved away from excessive monumentality and towards an understanding that prioritizes human scale and social sustainability.

Leave a comment