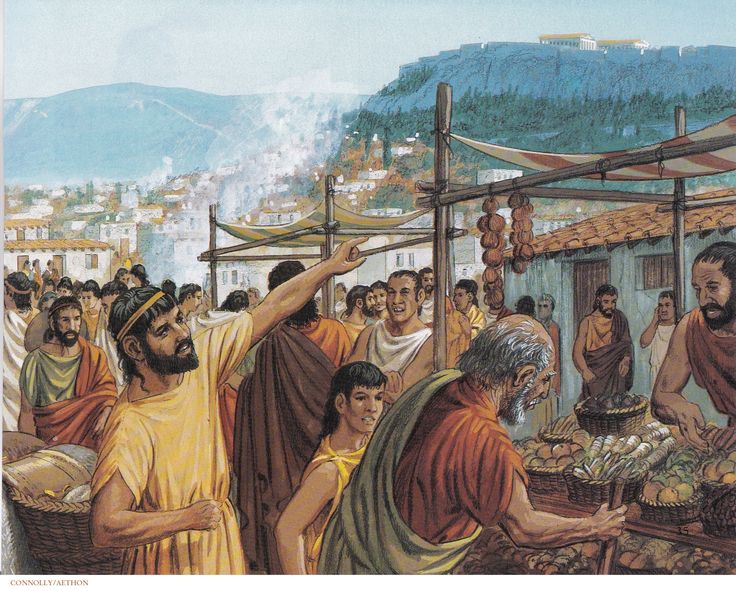

Public space developed from being a central marketplace to a space where people can go without aim or arrangement, as sociologist Ray Oldenburg once defined it in the book The Great Good Place in 1989. Its origin is often linked to ancient Greece: When Athens became a polis (city) around 600BC it meant having a central space, where the main exchange of goods takes similarly place like the social and political small talks and decisions. Such an agora (central gathering space for all kinds of activities) laid the foundation for a modern European understanding of public space – despite the fact that women were vastly oppressed and not allowed to take part in activities. Even the Roman forum is said to be modeled spatially based on the Greek agora. It is also here in ancient Greece, that the essential distinction of spaces was developed: On one hand, there is private space for the family and intimate friends, and on the other hand, there is public space for all kinds of activities for various kinds of people.

Fast forward to today, European public spaces still (try to) carry the ancient ethos of public space as a space for gathering and socializing. Perhaps, they are more reliant on CCTV and aimed at recreation or as infrastructural hubs, but many of them still carry the original sense or genius loci. They are the hearts of the city, so the question is raised, what will they be like in the metaverse and in the metacity?

In another article called Metaverse, The Upcoming Realm of Architects, we have discussed the design and role of architects when it comes to the planning of the metaverse. Here I want to concentrate on the idea and purpose of virtual public spaces in line with their design as well as on their legal framework. How does public space in the metaverse differ in design and architecture from the real and offline space? Is public space in the metaverse a copy of existing, real-life space? Who is in charge of it and what can one do there? What are the laws applicable in the metaverse? Are there any?

Not different from offline spaces, public spaces in the metaverse seem to be centered around social interaction. Herman Narula, in his recently published book Virtual Society, states: “Many kinds of real-world social interactions are potentially better suited for virtual space, if only for reasons of convenience. A political rally for a major international movement could involve fans and supporters from all over the world congregating instantly. A global university campus might exist, mixing students from everywhere in a context free from many kinds of discrimination.”

Additionally, virtual public spaces could be test grounds: “Merge of real and virtual: Eventually, virtual worlds will function as “what-if machines” that we can use to answer questions about things so that we can go from a society that is often stymied by complex problems to one that can learn how to better manage complexity in the real world.“ However, both purposes are only palpable if virtual public spaces are effectively accessible by everyone and are resembling real-life spaces. If a potential user has to pay with cryptocurrency to gain access to public spaces or needs VR-Goggles, these spaces are not yet truly accessible; And if these spaces serve as test grounds, they need to resemble our offline spaces.

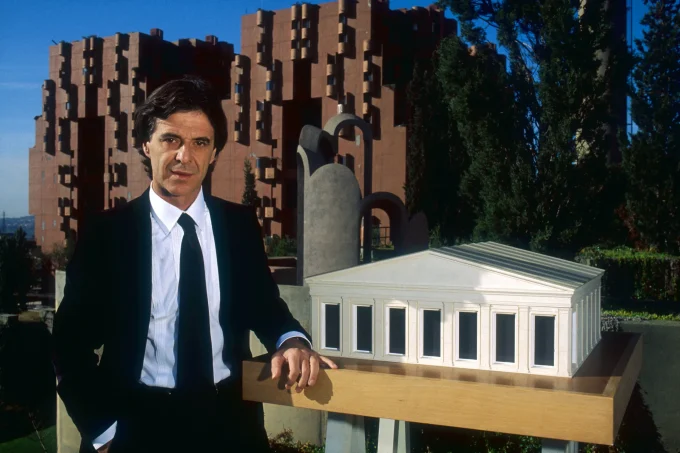

Those who have seen the first images of metaspaces space may have felt disappointed. One article by the Urban Design Lab describes the situation: “Right now the world of metaverse seems to be all merry-go-round and play, such as renderings in a simple graphic style, like a children’s TV show. Practical (yet unnecessary) design elements including streetlights, plug sockets, and window frames underline the urban nature of these sterile, current virtual spaces. The environment designers currently are choosing to plump for familiar architectural characteristics in their virtual buildings, because it makes it easier for participants to feel immersed. Though there have been attempts by architectural firms such as Zaha Hadid Architects to design cities in the Metaverse, these are still form-related exercises built on parametric design principles, which might become a new space for social engagement, only time will tell.” And indeed, Zaha Hadid Architects seem to have helped to push the boundaries of what public spaces in the metaverse could look like.

Whereas design principles vary, depending on who offers the metaspace and for what purpose, Breanna Faye, herself engaged in developing technologies for the metaverse and making it more accessible via NFTs, has listed the chances for meta public spaces in Medium. They can be …

- … open and accessible and owned by everyone

- … governed by everyone (with the help of DAOs)

- … opportunities for infinite land (there is no limit to the number of virtual spaces that could be built)

- … thought of from the start, instead of being an afterthought in urban planning

On one side, there is potential in designing metaverse public spaces from scratch, but on the other side, city governments around the world have started to make digital copies of their actual cities. Helsinki, Seoul, and Dubai have started to recreate themselves digitally. Helsinki was one of the first and started to invest in 2015 into a digital copy.

The company Zoan which created it has been mainly concentrating on the city center and offering walkable tours to locals and tourists alike.Zoan states on their website: “The ZOAN team initially modeled only a few of the central locations of the city: the prominent Senate Square, the iconic Helsinki Cathedral, the home of the legendary architect Alvar Aalto and the Lonna Island. Soon after, it was time to take over the entire city.”

All of this opens up a different way to think about the metaverse: It could be our actual real-life world, only safer, easier to access, and spatially “improved”. British people may enjoy a sunnier metaverse in times over a rainier reality and also Ukrainians may be given the chance to wander Mariupol before the Russians relentlessly commit destruction as an act of terrorism against it. In that sense, what is digital is stored and archived. And when a city is brought online, it is its public spaces – streets and squares – that capture its essence and atmosphere. The only remaining question is: What laws apply there?

The question of what is legal and not legal to do in public spaces in the metaverse is fuzzy. Hereby, it is a common suggestion that real-world laws would similarly apply in the meta-world. But it remains unclear if it is up to the governments to enforce these laws, to the producers of the metaspaces (after all, if one can do things in these spaces that cannot be done in real life spaces, for example being invisible, it may be also their responsibility to facilitate such spaces with applying laws) or if it is self-governed by the users. Such self-monitoring, often referred to as sousveillance has become the answer to government surveillance.

Already in 2008, in his book Learning to Act in the Metaverse, Sonvilla-Weiss asks: “A society fully wired and connected is prone to control and surveillance, even though civil counterstrike techniques aim for equiveillance, a state of equilibrium, or at least a desire to attain a state of equilibrium, between surveillance and sousveillance. Are these viable models that will protect us from total control? […] And do the virtual and the virtue, interpreted as inseparable experiences of the factual and the fictive, allow for another paradigm shift […]?” Especially if crimes are committed through an Avatar, the legal matter gets fuzzy: “[…] we need to attribute a legal persona to the avatar, giving them rights and duties within a legal system; allowing them to sue or be sued.” But this matter is not for the future and already now crimes occur: “Worryingly, sexual predators are already emerging in the metaverse, masking their identity behind an avatar that may not easily be traced back to its operator in the real world. For example, we’ve seen incidents of groping. Users in the metaverse can wear haptic vests or other technologies which would actually allow them to feel the sensations if they were touched or groped.”

It remains to say that in order to make use of the benefits of public spaces in the metaverse, it needs to be designed carefully or copied (and perhaps improved) from the actual spaces, made safe and legal authority must be clarified. Programmers need to be joined by urbanists, architects, and lawmakers in order to provide and ensure an enjoyable experience for everyone. But even before all of that, the essential question is: How can the atmospheres, meaning the sounds, smells, sunsets, winds, distant chatters, feelings of freedom, and possibilities, that so many of our great public spaces have effectively transferred into an authentic virtual experience?

Leave a comment