We live in the Anthropocene age. In other words, we are in an age when humanity has become the most important factor that determines the functioning and physical structure of the planet.

Although arguments exist for the recognition of the Anthropocene as a legitimate geologic epoch, this designation is still under debate by the various supporting committees and by the ultimate authority on geologic time scales, the International Society of Geologic Sciences. It seems that sustainability in the industry will not be enough to save the world. It is also not helpful to compensate for the damage caused by the economic growth-oriented construction activity, by planting new trees after destroyed elsewhere or designing roof gardens and green façades in architectural projects. These are just minor steps.

Leonardo Caffo (2018) characterizes the efforts made by “green” architecture as merely rhetorical and explains how the time has arrived to respond concretely to the impact of anthropization, concluding: “The future looks like a hut, not a skyscraper”.

If we want to deal with Anthropocene to be long-term, we can do this not only by reviewing our established practices but by questioning the conceptual framework and mindset that underlies these practices. With the expression of Agamben, we can do it by “secularise the sacred”. The practices that advocate being “nature friendly” and acting with the motive of “saving nature” must first be calculated, which is precisely the holiness they place on the concept of “nature” mentioned in these expressions. It does not work except believing that nature is self-treating, covering up the sociality of worldly issues, including it, and escaping from the political decisions that need to be made.

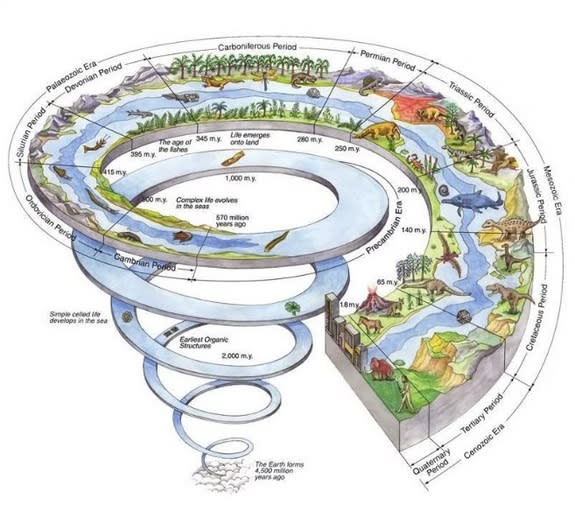

“The Anthropocene thesis not only challenges this inherited assumption but demands of it a fatal conceit. If the will to knowledge characteristic of modernity provided the assurance that the fault line between human culture and nature was indeed factual, the production of the Anthropocene counter-factually relieves our contemporaneity of the burden of perpetuating this epistemic illusion.” E. Tulip stated in “Architecture in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Design, Deep Time, Science and Philosophy.”

Again E. Turpin stated in their article, “On the Earth-Object, Paulo Tavares remarks: ‘Global nature’ is therefore and above all a space defined by a new socio-geological order in which the divisions that separated humanity and the environment, culture and nature, the anthropological and the geological have been blurred.”

According to Deleuze, the job of “creating problems”, that is, creating problems, is the main task of philosophy. With the provocation of the Anthropocene thesis, philosophy can produce new structures that transform thought trajectories; architecture can also discover its unique capacity to transform the present and future state of the World System by developing intimacy and cooperation with multi-disciplinary, multi-scale, and multi-center approaches. We lived together during this period. Architects, urbanists, engineers, sociologists, and philosophers should work together, seeing the many disciplines of this process.

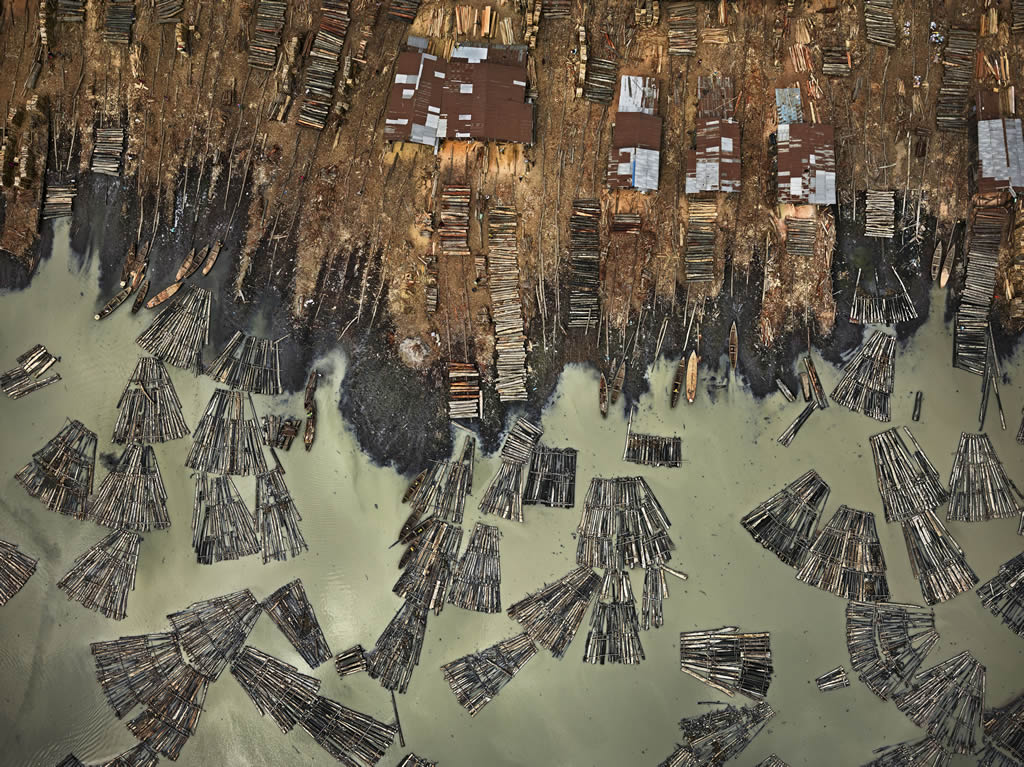

In “Urbanism in the Anthropocene: Ecological urbanism or premium ecological enclaves?”, Hudson and Marvin wrote about, urbanism encompasses the social, economic, and political processes most closely linked to the rapid transformation of habitats, destruction of ecologies, overuse of materials and resources, and the production of pollutants and carbon emissions that threaten planetary terracide. On the other hand, Architecture is not only about buildings; buildings are mainly stuff. Architecture is an active connection, a practice that activates a relation between material spaces and their inhabitation; and, it structures that relation, it structures what we call the relation between space and polity.

Cities are critical for comprehending global ecological change or crisis. Cities play a significant role in climate change because urban activities are major sources of greenhouse gas emissions. According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), cities are responsible for 75 percent of global CO2 emissions, with transportation and buildings being major contributors.

Cities are the material representation of today’s energy-intensive economies were (generally) carbon-based energy systems. The image of the city, in particular, as a thing that is made of geology, increasingly has to struggle with the idea of the city as a thing that makes geology, in the forms of nuclear fuel, dammed rivers, atmospheric carbon, and other products of urbanization whose impacts will span into future epochs.

Once constructed, urban environments can be slow to change. Buildings typically last for decades and infrastructure such as roads and pipes can last for centuries. Therefore, urban structures should be designed not only to meet the needs of today but ideally to meet the social, environmental, and economic needs of the long-term future.

As I mentioned before, The world is currently undergoing a period of rapid change, ecologically, socially, and economically. Anthropocenic change creates a new urban era much more unpredictable context for the longer-term development and reproduction of cities marked by climate change, implications for resource constraints, as well as energy, water, and food security issues.

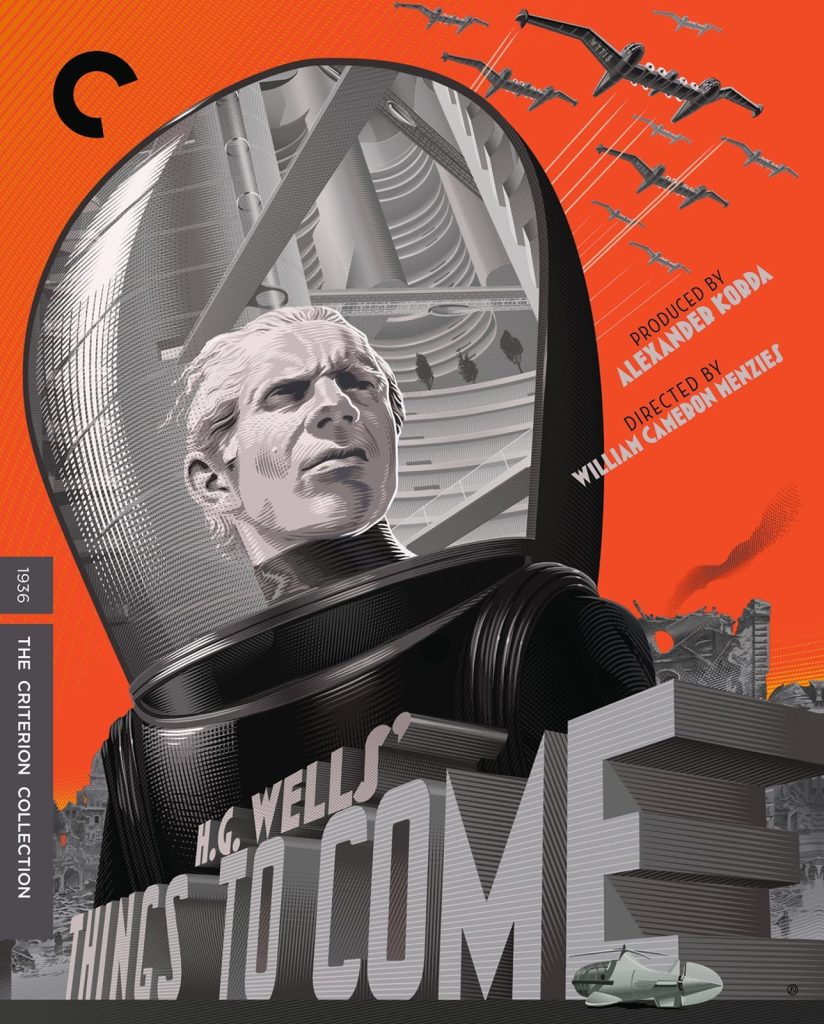

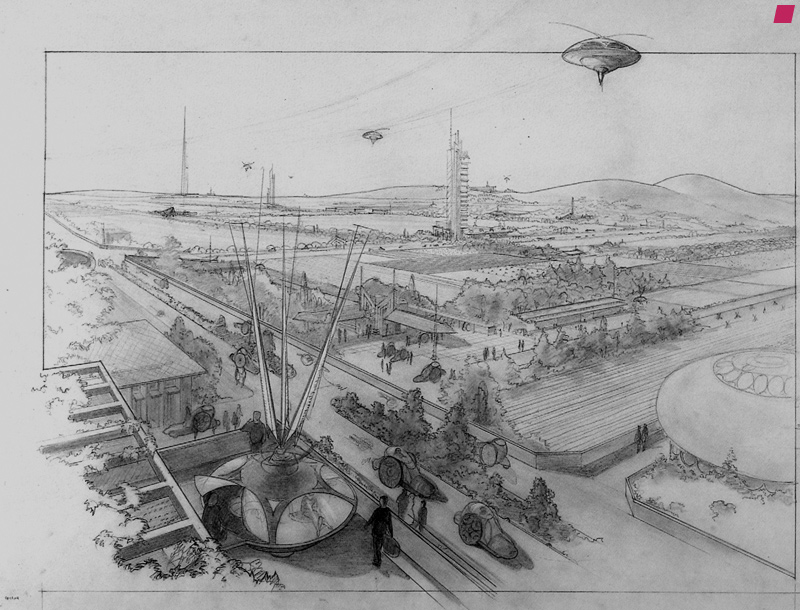

The basic approach of the theorist is to design the urban space biologically. In this way, they think that the economic structure can become compatible with nature. Similarly, Wells (1936) made the film “Things to Come” in the same period. In the film, architects and engineers, who create a “modern” city with biotechnical design and completely underground human production, save humanity from ecological disaster.

The fact that nature is on the main axis of the design seems to be related to the debates such as “breaking away from nature” and “social collapse” especially in societies after the industrial revolution. For example, for Wright, the relationship between humans and nature, and his nature constitutes the main axis of architecture, while for Aalto, the divergence of human psychology from nature.

Wright (1956) considers American cities of the period as “overgrown villages, places where people suffer while living” that cannot meet the spatial needs of modernity. Broadacre City, organic architecture in urban space theory. It reflects the search for democratic space. When we look at the “Waterfall House”, another design by Wright, he said, “I want you to live with it, not to look at the waterfall, the waterfall must be an internal part of your life.” It can be said metaphorically that with the project, the waterfall, residence, and family become together.”

From the frameworks made in the context of Anthropocene theory, “nature and human unity” corresponds to the main problem of modern architecture regarding the environment. Unlike the other two parts, the concept of nature-human association aims to achieve a hybrid harmony between the two rather than the rehabilitation of nature or modern humans. Looking at the early modern architecture theory, the problem for Mackintosh is establishing the relationship between industrial materials and local architecture, hybrid mechanization created between urban space and rural for Howard, and for Berlage, workers coming from rural to urban to work in the industry.

“Technological structuralism” has been defined as the closest design approach to the Anthropocene Age. Technological structuralism is, in a sense, the process of restructuring nature through technology for the needs of modern society. According to Fuller (1963), the world is in great social and ecological distress due to population growth and energy shortage. According to him, this problem can be solved only by meeting people’s housing needs and saving energy.

Technological structuralist architects have influenced contemporary building design processes by being in line with sustainable building certification systems such as LEED and BREEAM. Especially in the last two decades, environmentalist approaches in architecture converge into a pragmatic process, influenced by these two different actors.

The first separation in the Holocene-Anthropocene for architectural theory is the transition from primitive architecture defined by Rapoport (1969) to local architecture; the second architectural transformation from local architecture to modern is a transition to architecture. The nature-human relationship for Wright.

The prophecies of “The Limits to Growth”, the famous Meadows Report of the Club of Rome in 1972, have almost come true: climate change, loss of biodiversity, sea-level rise, refugee crises, new conflicts, etc. All cities, from earthquakes to floods, from rapid migration to unlimited urbanization, are facing a series of new and strengthened shocks and stresses, both natural and human-made. This factual increase increases the exposure and vulnerability of citizens and people to different dangers, triggers, or worsening disasters. As the effects of climate change become more severe and frequent, more stress is applied to our urban areas.

As a concept that has recently gained popularity and acceptance, urban resilience is the ability to withstand destructive challenges and recoil, involving various risks present. Flexible cities are planning and acting to reduce the risk of floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes. Today, dealing with flexible, sensitive, adaptable, interconnected, and rapidly changing global conditions is the most difficult situation. In the face of such negativity, we watch (unfortunately) the formation of a new consciousness; centralism and decentralization, industry and ecology, technology and craftsmanship, fertility and economy, locality and sphericity, expression of work and play, education and life, diversity and unity, loneliness and sincerity. It seems imperative to increase resilience in our cities by strengthening the abilities of cities and urban people to reduce these changes and reduce their negative effects on people.

In Anthropocene, it is perhaps more correct to conceptualize the so-called new normal – or new abnormal – life; It is characterized by uncertainty, unpredictability, real chaos, and brutal change. This planetary distress makes itself felt every day with global warming, climate change, variable air-soil-water, acidic oceans, disease outbreaks, endangered and extinct species, biological accumulation of toxins, and the overwhelming physical impact of an exponentially growing human population.

The Anthropocene concept brings together all these factors and others, even when each counted factor is on its own. This is the only way we can understand the Earth as a single ecosystem with recycling and notification cycles and tipping points that we haven’t yet predicted.

Urban resilience and age of the Anthropocene

Townsend (2013), at this point, the city plays a role as an initiator and consequence of the Anthropocene; It is a form of spatial and infrastructure that can enable us to double our industrialization by eating our cake by redesigning the operating system of the last century. On an urban scale, it is clear that they have analogies; the analytical object is rapidly transformed in unprecedented ways as cities grow to unprecedented levels in human history. The absence of any known foundation and the need to adopt “new ecologies” or constantly moving balance points create both scientific and political concerns. These concerns are calmed or cut in the form of urban and environmental “legibility” produced by “big data”.

Urban resilience is a measurable ability of any settlement system to be positively adapted to sustainability while maintaining continuity with its residents, with all the shocks and stresses. A resilient city evaluates, plans, acts, and positive changes to protect and improve the lives of its people, secure development gains, improve the investment climate, be prepared for and respond to natural and humanitarian, sudden and slow starting, expected and unexpected hazards and to respond to them.

Floating cities in Bangladesh can be given as a good example for learning about the climate crisis and “remembering to live with nature” at this age. Sea level rises rapidly in Bangladesh. Bad weather and rising sea levels displace many people. Monsoon rains, which have been falling throughout the summer, stop life. A large part of the country is submerged from June-October. Due to climate change, a significant part of Bangladesh is expected to be submerged in the coming years. As one of the regions with the highest population density in the world, important life problems such as health, clean water, and medicine create big problems related to needs.

There were two important points regarding the project in Bangladesh: Rising water levels and dry land under threat to be protected. The region should be physically and socially evaluated and decided. Project director Mohammed Rezwan believed that local solutions should be developed for local problems. Values, cultures, traditions, and priorities are peculiar everywhere; these are issues that require a sensitive approach in times of crisis. The process focused on the importance of the place of water transportation in the culture and history of Bangladesh.

The element that threatened them was also the solution that would save them. This bond and heritage from the past should be evaluated. The challenges of the twenty-first century – resource constraints, financial instability, inequalities within and between countries, and environmental degradation – are a clear sign that the usual routine cannot continue. We are entering a new stage of human experience and we are entering a new world that will be qualitatively and quantitatively different from what we know. Cities around the world are linked together in a series of interconnected demographic and environmental pressures. For cities and their inhabitants to survive and develop, they must be well-coordinated and respond effectively to different pressures.

Urbanization processes trigger the change in Anthropocene, revealing unprecedented environmental and social challenges in scale, scope, and complexity. Additional uncertainties by putting pressure on climate change, adaptation to local institutions, and resilience. Bringing aside the actors and resources required for the cities to effectively set and maintain key functions, it focuses on the concept of “urban resilience”.

In conclusion

Anthropocene is an independent measure of the scale and tempo of human-induced change – biodiversity loss, changes in atmosphere and ocean chemistry, urbanization, globalization – and places them in the deep context of world history. The resulting Anthropocene the world is a warmer world with a decreasing ice cover, more seas, and less land, changing precipitation patterns, a strongly modified poor biosphere, and man-dominated landscapes.

Although we have tried to establish a new and livable society around concepts such as democracy, sustainability, sustainable development, resilience, and adaptability; All these terms have been disrupted by these forces, because they are normalized, included in the Anthropocene where they do business as usual, and try to be placed.

We are the first generation to have a broad knowledge of how our activities affect the “World System”, so we are also the first generation to have the power and responsibility to change our relationship with the planet. If we cannot manage the Anthropocene correctly, we will face the threat of embarking on a one-way journey in a new but very different state of the World System towards an uncertain future for humanity.

Unfortunately “human” turns into a problem for ecosystems. As we have been pushing the boundaries of the ecosystem quite a lot, we do not have the chance to be the first to escape the sinking ship. Where is the left to go?

Leave a comment