Fresh Food for Thought was designed by Claire Tokunaga & Dami Akinniyi as part of PAACADEMY‘s “Parametric Design as a Catalyst for Social Innovation” with Nuru Karim. During the studio, participants explored computational design’s role in creating resilient, sustainable environments catalyzing social change & innovation.

Parametric Design can be used as a catalyst for social change. “For Fresh Food for Thought” team, was a way to address the topic of food security and explore how design can impact food production. Food is directly linked to an individual’s health and wellness as a basic yet critical human need. Food has become an expression of identity, uniting communities across cultures. Still, it has the power to create fear for those with inadequate supplies. With a topic as vast as food production, the team identified three objectives to address: its human, environmental and economic impact.

To begin, the group researched the human aspect of food, including how healthy eating habits are currently marketed, what some existing practices were around local food consumption, and the availability of diverse food in marginalized communities.

With unlimited data quantifying food scarcity and access disparities across socio-economic levels, they learned there are 720-811 million people in the world facing hunger, defined by the UN as going entire days without eating due to lack of money or access to food. Another 2.37 billion people face severe to moderate food insecurity with inadequate access to food, which translates to the fate of roughly one in three people.

In the US, 23.5 million people live in Food Deserts which identifies areas that don’t have access to a grocery store within a distance set by the USDA.

Food Swamp can be used to describe several parts of NYC that are inundated with more unhealthy, high-caloric food options than retailers selling healthy food. This lack of access to nutritious food is a phenomenon that happens in both rural and urban areas, developed and emerging cities, and increases the risk of health issues to its population.

Another consideration of food production is its impact on the environment. Many existing agricultural practices harm the environment, such as deforestation, loss of biodiversity, or overconsumption of water. In addition, our food travels 1,500 miles on average from farms to retail outlets, emitting 4.8 metric tons of CO2 along the way. Thankfully, food production has begun to move closer to where we consume it. Soil-based farming can be readily found in urban locations, from open-air rooftops to controlled indoor climates. Vertical farms can increase the volume of food produced per area while consolidating water & energy intake.

Advancements such as aeroponic watering systems spray mist directly to the roots providing water and nutrients while reducing overall water consumption by as much as 98% compared with traditional soil-based food production. The team knew their design wanted to harness this existing technology to produce a sustainable farming practice while minimizing its carbon footprint.

The last component they wanted to address was the economic model within food production. Globally, about 1 billion people work within the agricultural sector, with about 28% of the population employed in 2018. And while affordability is cited as one of the main reasons people are priced out of healthy food options, consumers are not filling farmers’ pockets. 84% of the price people pay goes to food supply-chain industries such as wholesalers and transportation companies, not the food producers and growers. After learning this, the team knew it was yet another reason to minimize food transportation and empower farmers, particularly those in urban farming.

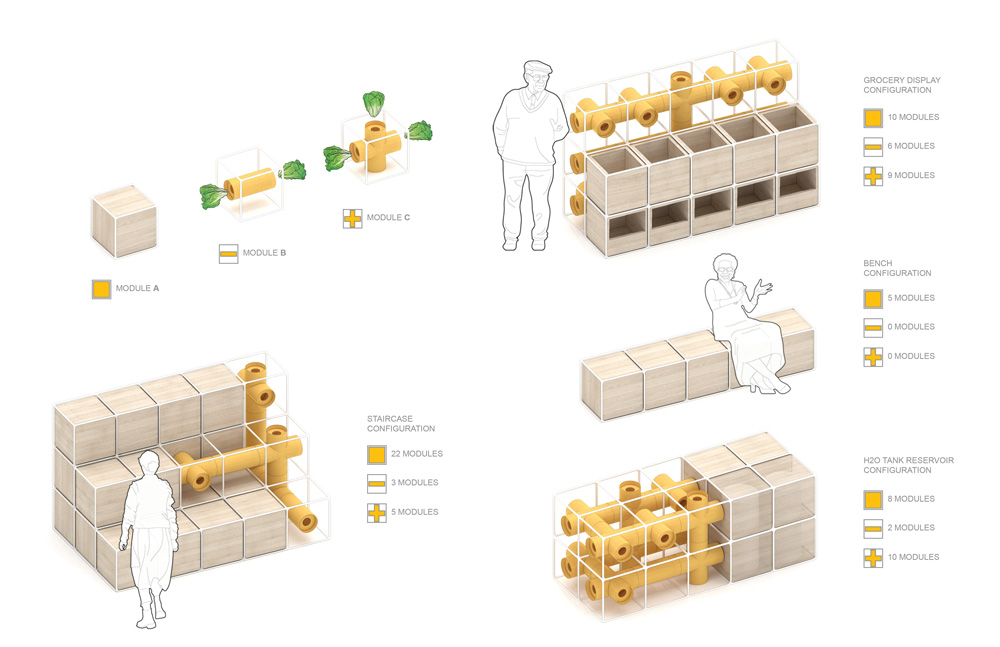

With the background research fully underway, they knew their design strategy had to be easily applicable in various contexts to achieve a democratic application. It needed to use readily available materials and be easily constructed by the community without needing advanced training. Another objective was to make each module structural and load-bearing so that it could be used as a building material and negate the need for additional components. Starting with the size required for a single plant unit, the team identified three functions to address;

(1) the structural framework,

(2) an area to house infrastructure like pumps,

(3) a tubular component that would both house the plants and be fitted together to create a closed loop for watering and filtration systems.

These three functions were distilled into the three modules shown in the diagrams. Using the Wasp Plug-in for Grasshopper, we created a script to aggregate the three modules to accommodate every site condition uniquely.

Furthermore, the “Fresh Food for Thought” team was working with the three modules as a kit of parts, the Grasshopper script was written to quantify each module type. If, for example, they needed more porosity because they needed more sunlight or better views, they would be able to decrease the number of most opaque modules (Module Type A) and increase the modules with the most openness (Module Type B).

Used differently, controlling the quantity of each module type would allow us to do a quick cost analysis of the completed aggregation and reverse engineer it if a client came in with a budget to work with.

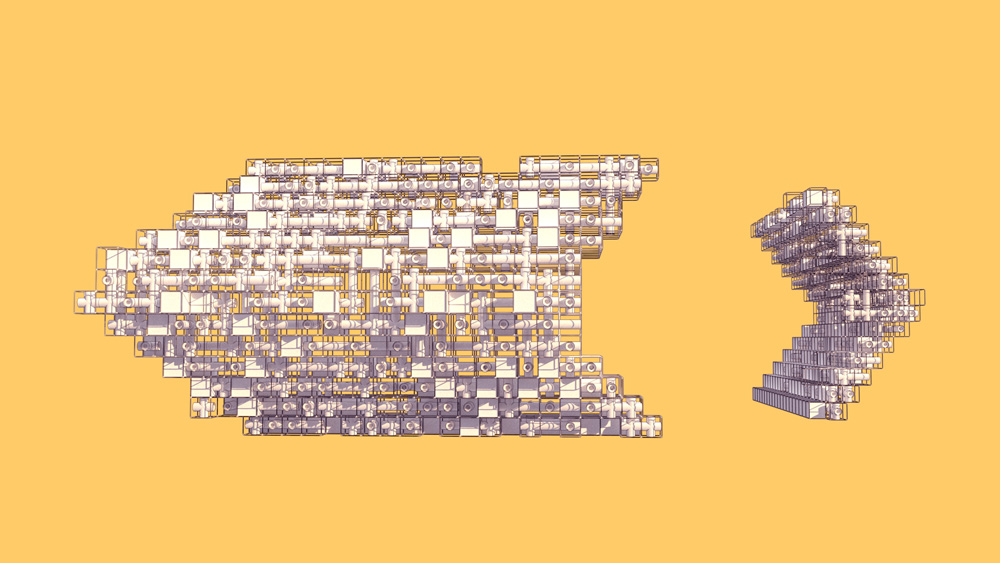

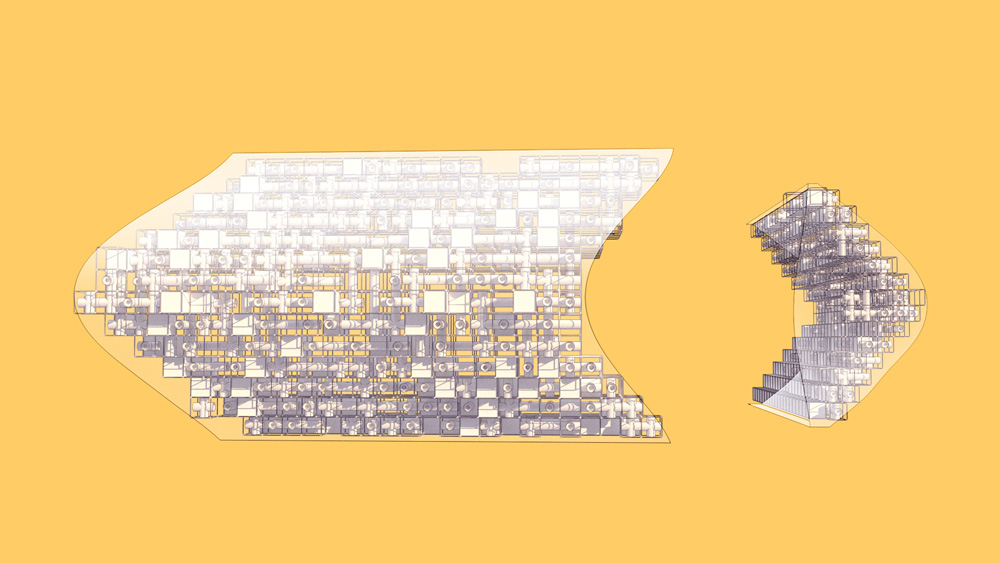

With the script and framework in place, the team wanted to test out the scalability of these modules. They selected (2) locations with different site conditions. The first location was in the South Bronx of New York, and the second was in Lagos, Nigeria.

Many Bronx communities can be characterized as a food swamp where there can be as many as 35 bodegas to every supermarket. The convenience of the corner bodega is unquestionable, but the availability and emphasis on fresh food are often limited. Processed and sugary foods are displayed at eye level. In contrast, the number of unhealthy food advertisements is 2x higher than marketing for healthy food options. Within this context, the site they selected was the ubiquitous corner lot with a bodega on the street level and apartment units above.

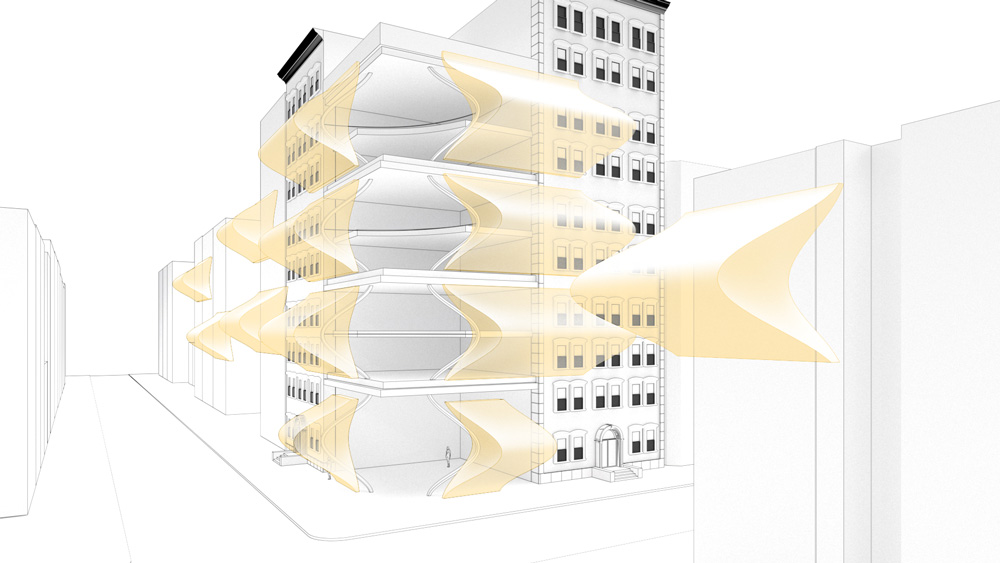

The modules were aggregated to become the facade of the apartment building, showcasing and immersing the tenants within the vertical farm that supplies the bodega with its produce. The curves in the facade create balconies that also increase the surface area for harvesting and provide easier plant access. They imagined these new balconies wouldn’t stop at the edge of the building but would extend beyond it. Balconies filled with greenery should not be a benefit of only new construction but something that can be added to existing buildings as well.

The team imagined transforming the cityscape, often referred to as a concrete jungle into one lined with floating gardens. The gardens serve to feed their users and promote awareness toward healthy eating. Suppose they cannot change the residents’ shopping habits away from the convenience of their local bodega. In that case, the design aims to bring the product to the residents.

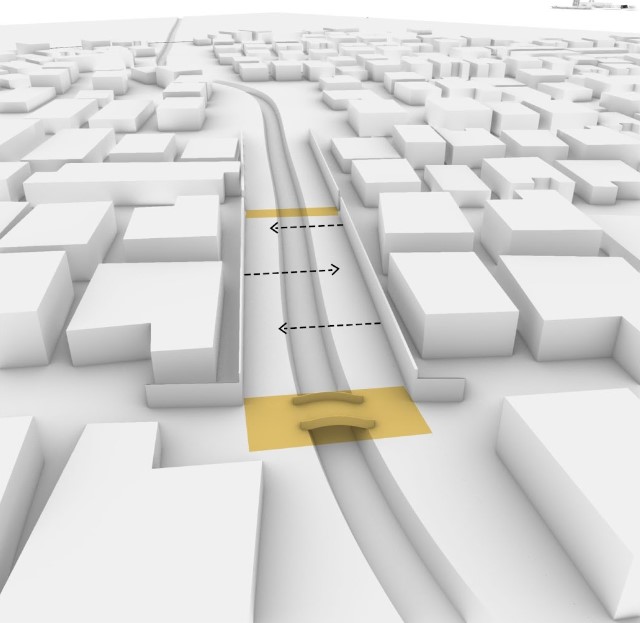

Half a world away, they tested the modules in a second location with a completely different set of parameters: Lagos, Nigeria.

Lagos has tiny, vein-like water canals that run throughout and serve as this coastal city’s drainage. While these canals are helpful in theory, the practical application has failed because the canals are not well maintained and are clogged with plastic waste and pollution. The stagnant water creates health issues, while the canals bisect streets and separate neighborhoods. This causes mobility issues; as a result, people have built ad-hoc footbridges to cross the canals. With irregular crossings over the waterways, the canal edges have become populated with various economic activities capturing people walking by.

Leveraging these existing conditions, the design aims to clean up the canals and repurpose plastic waste as the principal material for our modules in Lagos. Using the long stretches of canals running for kilometers through the city, the overall form of our vertical farm would ebb and flow along the canal’s edges to address the neighborhood’s needs. New bridged connections were designed to work with the sinuous aggregated form.

The curves form overhangs and pockets of sheltered areas, creating spaces that could be used to host events and classes that teach effective food production. The staggered stepping would allow for optimal sun exposure. Still, it could also serve as a display for produce to be sold or an amphitheater of seating for gatherings. Unlike the Bronx’s design, the overall configuration runs low and horizontally to ensure food production and harvesting ease.

From what the team learned in these two locations, the power of parametric design allows us to optimize what works well and iterate to solve what needs to be improved. This inherent circular workflow allows the design to continue to evolve and adapt to the complexities of the conditions and the people it aims to serve. This is perhaps the ultimate appeal of parametric design: as circumstances change, the design can change with it and thus create lasting social change.

Leave a comment