The narrative is a very important thing in architectural design projects. Each design must have a goal and a design idea. However, those design ideas don’t have to be focused on narrative; occasionally, it’s more focused on function rather than story-telling. There have even been some debates about this dilemma, like “Less is more” and “Yes is more.” “Funct over form” or “Form over Function.” Believe it or not, the same discussion happens between Game fans, designers, and scholars.

In each game we play, there is a story, sometimes a game designed around a story or the other way around. What do we mean by a game designed around a story? Well, we are talking about “Game Mechanics”. Game mechanics are fundamental designs in the game that determine playability and interactivity. Are we able to pick that axe or not or go to the forest whenever we want? Simply mechanics and functions of gameplay. Sound familiar?

We can say that game mechanics match with functionality in architecture. On the other hand, there is “Narrative”. Some players believe the story is a must in games since it’s an interactive media tool, and we can demonstrate our stories and ideas with it. If we try to a similarity in architecture we can say this section is “Form”. Determining form to express our ideas.

On the other hand, some players think narrative limits the game mechanics and the gameplay. You can’t go to the forest in the narrative because our character is afraid of wildlife. They believe in narratives and are turning games into interactive cinema when games have many more possibilities. It is simply a debate between self-claimed Audiologists (person who studies games) and Narratologists. Does this sound familiar as well?

Henry Jenkins (Henry Jenkins III) is an American media scholar and Provost Professor of Communication, Journalism, and Cinematic Arts, a joint professorship at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and the USC School of Cinematic Arts. He is a well-known scholar, especially for his research“Game Design as Narrative Architecture.” In this article, we will explain one of these narrative types and its similarities in Architecture.

Jenkins says that “game designers are less as storytellers and more as narrative architects.” the reason behind this is that in every game design process, you have to design its world as well from its culture to its architectural language. If we have to give a simple example, we can say myths, heroes, and quests. When those are written, they also create a fantasy world in it.

In “Game Design as Narrative Architecture,” there are 4 types of narratives: Evocative Spaces, Enacting Stories, Embedded Narratives, and Emergent Narratives. We are going to talk about Embedded Narratives.

What is Embedded Narrative?

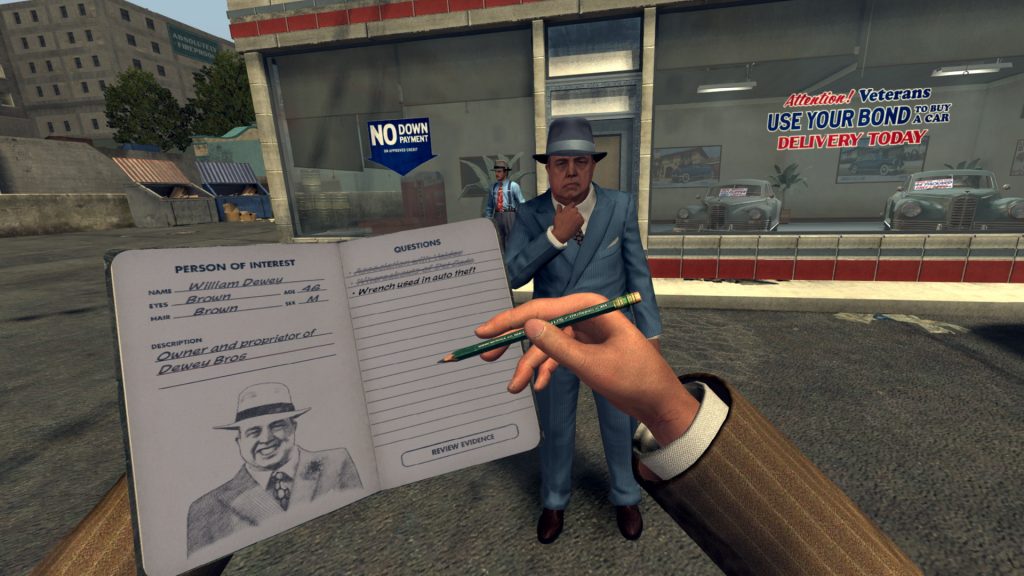

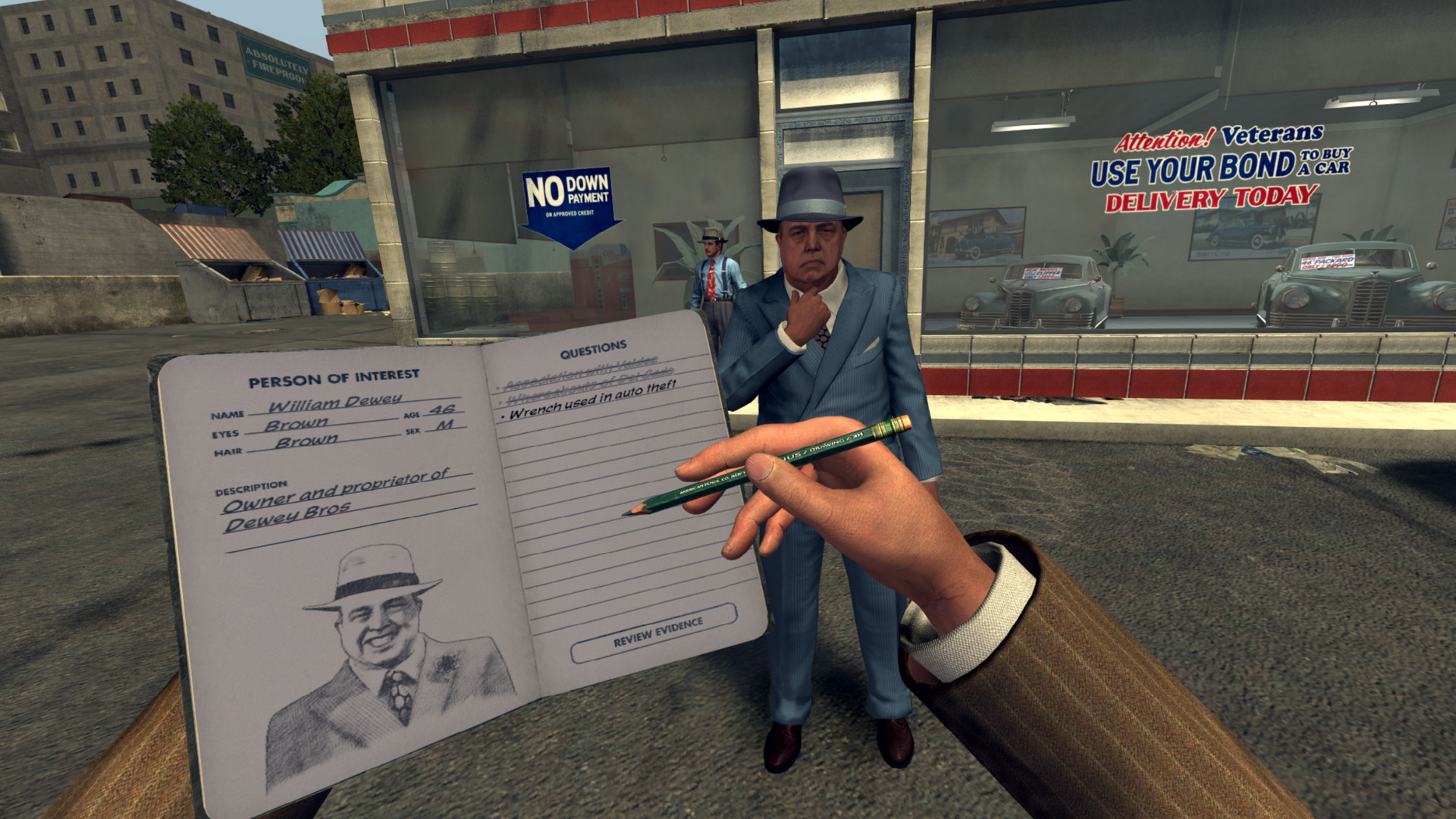

What is embedded narrative? This narrative type comes from cinema. Since games are media tools they will find references from other fellow media tools. However, we are not telling every kind of movie type. The best example we can give is Detective movies, the narrative of two stories. The first story is about how our protagonist solves the mystery which we can witness throughout the movie, the second story is about the murder. However we do not see or hear the murder story, we read it from the crime scene. Such as when we see a wall covered with blood and find a small note that says “Joe did it” we understand that Joe is the murderer, we are simply reading the space, and that’s the embedded narrative. A story that is embedded in the space.

Therefore, when a game designer uses this style, they have two stories in the game. First, the game story we are playing, our character’s story which is structured by the designer. The second one is the mystery story behind the current situation, but to uncover this story, the play has to explore the game space.

An Example of an Embedded Narrative: Unpacking

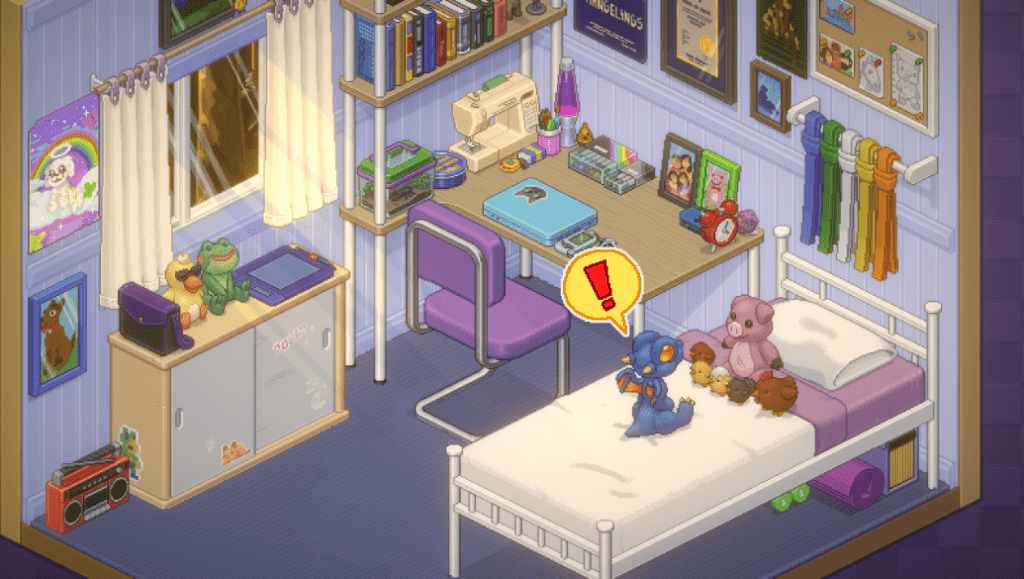

If we need an example, there is one game that recently won the BAFTA Award for Game of the Year and the Games Award for Narrative, Unpacking. Unpacking is a simple puzzle game developed by Witch Beam. The mechanic of the game is you are in a room and required to unpack your stuff and put them in right place. The game is about the life journey of a character whom we never see. We read her journey through her stuff like a toy from her childhood or seeing a torn picture that represents a break-up.

Each time we solve a room, we jump into a different time in her life and a different room. From her childhood to college life and, in the end, her own family. The narrative here is without getting to know a person or even seeing them, knowing them, just looking at their stuff. Reading their stuff, getting to know their personality and the difficulties they get through. A torn picture of a couple can indicate a break-u,p, and a teddy bear someone keeps until their adult life shows there is still a child part in themselves.

This is one of the best embedded narrative examples we can give, just reading through the environment and elements in that environment and getting to know the story in here is embedded narrative. Besides, this game resembles the idea of architecture, not the design part. What I mean is, we as architects try to tell a story with our design, each element or material we determine is either about a function or a connection to the site, which our decisions had a uniqueness to that site, a story. The resemblance in here this game tries to tell a story with personal belongings and every one of our personal belongings does have a story, each one of them unique for us. Things that we care about.

An Architectural Example of Embedded Narrative: Jewish Museum

When we think about it, embedded narrative is everywhere in architecture; however, it’s not that easy to determine. Some structures might have stories, and some might be just empty pages, but narrating emotions is extremely difficult since we can’t use abstract materials like games. However, there is one example we can talk about: the Jewish Museum.

We all have a brief knowledge of the Jewish Museum in Berlin which is designed by Daniel Libeskind. This zigzagging build was a competition project held in 1988 for an extension to the original Jewish Museum. Libeskind responded to the competition with a narrative-driven design called “Between the Lines” cause for Libenskind it was about two lines, a straight line that is broken into fragments and a torturous line that continues indefinitely. The concept of the design is to express feelings of absence, emptiness, and void. We see small cutting lines on the façade like a wounded structure; however, those lines, from time to time, provide light in the void and sometimes create a feeling of discomfort. That’s what the designer tried to achieve, he even mentions sometimes building is not something comforting.

From this analysis, we can see there is an embedded narrative here, a story we are experiencing, and a story hidden in the structure. But what makes the Jewish Museum special? Well, Games have the advantage of being in an abstract space; therefore, expressing emotions is easier. However, here, you can’t play the space as much as you want; in the practical world, you have a challenge, especially if you are trying to express emotion, but that does not stop us from trying.

Game design as Narrative Architecture is not just for the game designer nor for architects. This research is actually a universal statement. These narrative types can be used in any field that wants to communicate to the public. This is not the end of this discussion, we will talk about other narrative types that are used in games and again we will give examples in both fields, game, and architecture I guarantee you that there are so many common points here, we just don’t see it but we know it.

Leave a comment