The possibility of artificial intelligence replacing creative jobs – as such, architects might be counted – remains vastly uncertain. Opinions claiming that AI can fully replace architects are similarly present as opinions claiming the exact opposite. A main variable, at the moment, remains to what extent AI will progress and develop: Currently, not all common architectural tasks can be replaced. However, fast forward, it is not impossible to imagine that AI, as this technology becomes more diverse, widespread, and advanced, can fully replace the architectural profession.

When this point comes, there comes a question alongside it: Are we willing to replace it? Are we willing to replace essential human abilities such as emotional intelligence and social interactions? In other words: Will any romanticization of human capability to be creative and emotional intelligence stop AI from completely replacing the creative industry? In this essay, I will shed light on some of the key considerations surrounding this topic that can, effectively, neither take away fears nor hopes for architects. Foundationally, it is also a question of morality and the ethics of technological progress in capitalism and, to what extent, architects are themselves willing to adapt for the future – before ‘this’ future forces them to adapt.

In a 2013 Oxford study titled The Future of Employment, the risk of various professions being replaced by robots and automation is assessed and architects have a very low risk of such with only 1,8 %. If one asks the willrobotstakemyjob, architects have an even lower chance with 0 %. To understand these results better, it is important to dissect the architectural profession into its tasks. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics adds the following tasks for architects in their Occupational Outlook Handbook:

- Meet with clients to determine objectives and requirements for structures

- Give preliminary estimates on cost and construction time

- Prepare structure specifications

- Direct workers who prepare drawings and documents

- Prepare scaled drawings, either with computer software or by hand

- Prepare contract documents for building contractors

- Manage construction contracts

- Visit worksites to ensure that construction adheres to architectural plans

- Seek new work by marketing and giving presentations

Some of these tasks might be more easily replaced by an AI or advanced software, while others take longer to be replaced or are not desirable to be replaced at all. Already now, there are many AI tools, such as image generators, that architects make use of, including but not limited to DALL-E 2, an AI-powered image generator developed by OpenAI; Midjourney as a text-to-image generator with hyper-realistic images or NightCafe, being among one of the best AI image generators so far on the market. A more complete overview can be found here. Keep in mind that here, only AI tools are listed and therefore software or VR tools are not counted.

Check PAACADEMY’s workshops to learn more about how architects use artificial intelligence to design.

Nevertheless, whether AI replaces some components of the architectural profession or not, the main question remains if AI can (and should) replace those components of the job that are distinctively individual and creative. To answer this, it is worth pointing out the current advantages of human workers over technology. David Mosen in an article titled Can Artificial Intelligence Replace Humans in Artistic Jobs? for Crayon pointed out that AI is lacking any emotional intelligence: “Emotional intelligence is the ability to understand and respond to emotions in oneself and others. This is important in artistic jobs such as acting or writing, as it allows the artist to connect with their audience on a deeper level. For example, a human painter must not only choose the right colors and brush strokes but must also have a deep understanding of composition, light, and shadow.

AI can mimic some of these processes, but it cannot replicate them all. It will always fall behind humans since AI will always be trained on human data. In addition to lacking creativity, AI also lacks the emotional connection that humans have with art. We create art because we want to express our emotions and share our experiences with others.” Whereas this is true, the more fundamental question will be whether that is seen entirely as a shortcoming of AI or can perhaps, by tech companies selling AI tools be reversed into displaying the emotional intelligence of humans as an emotional weakness in a capitalist system, where productivity and efficiency determine the market. The second – and perhaps main component – is the idea of their creativity, imagination, and taste, acquired over years of studies and work.

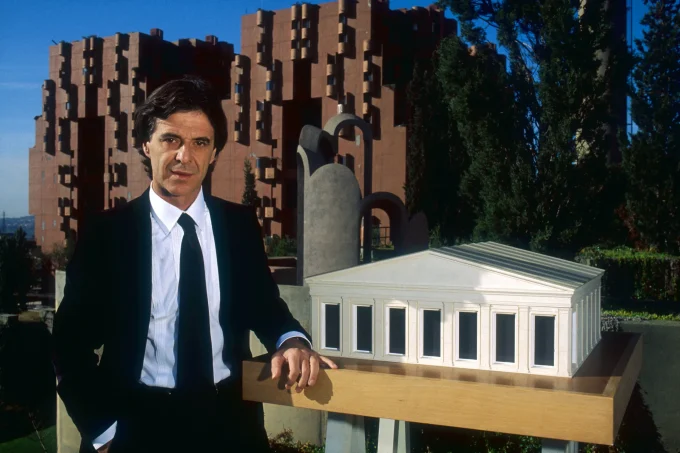

In the article, Rise of artificial intelligence means architects are “doomed” says Sebastian Errazuriz, the designer states that only very few architects will survive: “Architecture as an artistic practice is the only one that will survive and it will be developed by a tiny elite. We’re talking five percent, one percent of architects max.” In other words, some architects, whom one may think of as ‘Star architects’ might be valued for their acquired taste and distinct design language over AI, but for the most part, AI might replace this creativity with data, advanced algorithms, and adaptive learning.

The third component of the architectural profession (that might survive) is the aspect of efficiency. It is easy to understand that an intelligent machine (in whatever form it will come) can quickly process a vast amount of data, taking into consideration the available budget, geographical location, and needs of the client in terms of the size of the project and floor plans. However, here AI designs and computes with an idea of efficiency: How can the cheapest, most efficient, livable space be produced? In that sense, it does not take into account that not all spaces, such as parks, public spaces, buildings with a representational function, or monuments, need to be efficiently designed. Humans, with their emotional intelligence, are able to plan for uncategorizable variables and might take symbolic values into account. Based on which logic, for example, would AI plan and design the Sagrada Familia?

Lastly, it is difficult to imagine one, single AI replacing the whole building process. Even if architects were fully replaced, how does this AI communicate to clients, construction workers, and engineers in their respective languages? This aspect of the architect as the organizational mastermind behind a project seems difficult to replace overall. Of course, on some scale, AI can produce a complete design and communicate that design to another AI connected to a 3D printer, as we discussed here, to erect this building. But still, here and there, human interference would be needed, such as by delivering the materials, making this AI connection happen in the first place, controlling the functionality and correct operation of that AI to AI connection.

The article, Will Artificial Intelligence Ever Replace Architects?, summarises the situation as follows: “AI can perform many different services useful to an architect. The generative design allows for variations on a model to be composed and tested, and design alternatives to be presented for consideration. This element of randomness allows for possibilities to be struck upon that might otherwise never have been examined. AI also allows for more efficient interactions between the various parties collaborating on a construction project. AI-powered designs are far less likely to overlook any key component, whether it’s the architecture itself, or the mechanical, electrical or plumbing plans.” But “[i]n theory, there’s nothing that could fundamentally prevent an AI from designing a building.”

Concluding, there are two thoughts that we want to share with you. For one, as with any technological advancement, architects should not fear technology from a passive bystander point of view but highlight the essence of their profession – that is, to offer a creative, meaningful, and pleasant spatial solution for a given framework of variables. Architects should rely on software wherever needed and desired, but by doing so should not forget their own value in terms of emotional intelligence, creativity, and social interactions involved in any project.

Secondly, not every technological advancement needs to be accepted deafly and blindly. Rather, essential questions need to be asked: Even if AI can design my house, do I want that to happen? What is lost or gained when handing over tasks to machines? These questions are almost never asked but are highly relevant from a philosophical point of view. It would probably be wise to avoid architects having to step into direct competition with an AI when it comes to an architectural project, such as when there is an Open Call and entries from architects and AIs alike are submitted. With that in mind, it is probably now more time than ever for architects (and any creative worker) to highlight and focus on the heart of their creative profession.

Leave a comment