High-Tech Architecture originated in the 1960s and had its heyday in the 1980s but continues to play a relevant aesthetic role until today, depending on the definition and interpretation of ‘high-tech.’ In this article, I will work through the main characteristic of this rather dystopian-looking style, show various examples, including the formerly most expensive building in the world, and explain what can be learned and taken from this style for the future, especially for a highly technological one.

The Origin

Modernism in architecture did not automatically turn into Postmodernism. Between the late 1950s and the late 1970s, architects ventured through a period of experiments. During this time, one may find Brutalism, Googie-style, early Deconstructivism, New Formalism, the standardized housing typologies of the Soviet Union, late Stalinist architecture, Pop-Art architecture, and also High-tech architecture.

These years are still characterized by the post-war period and its search for reliable, flexible, affordable, and refreshing formal solutions, mainly for residential areas. On the other hand, these years lack the boldness and stylistic freedom that postmodernists introduced to art and architecture only a few years later, mainly through questioning the formal strictness and truths that modernism sought to offer.

As art and architecture generally reflect on societal progress made on cultural, economic, and technological levels, these years mark the beginning of a whole array of such progresses and inventions: the space explorations starting with the Russian satellite Sputnik followed by the American moon landing in 1969, the hovercraft, the transistor-radio, the portable cassette player, the floppy disk and most importantly, the computer.

In recent years, humankind has wandered from analog to digital, invented coding languages, and been able to get weather data from space. During this period of progress, low-tech became high-tech: literally, the term high-tech originated from a newspaper article in 1969. Therefore, it seems as if the term ‘high-tech’ arrived later than the earliest high-tech buildings, which may just show how quickly and progressive this period was.

High-tech architecture

But High-tech architecture is an often forgotten style of architecture and, at best, known to be used in science-fiction comics such as Ghost in the Shell. It is often forgotten because only a dozen high-tech-styled buildings have been built, and almost all of them are situated in the United States, the United Kingdom, or Hong Kong.

This may have been because this style is not very suitable for a variety of buildings – one may imagine a residential building looking like a factory – but also because buildings with chrome, metal, and glass are incredibly expensive. Nevertheless, such high-tech architectures tend to fascinate and surprise its spectators, whether negatively or positively, mainly because these buildings have a catchy roughness and rawness to them, are impressively technologically looking, and appear sometimes like they are still under construction.

To better understand this visual language, I will borrow the words from Edwin Heathcote from the Financial Times, in an article called How ‘High Tech’ became the architectural style of globalization noted that high-tech architects cherish “huge structural elements which are made very visible: snaking ducts; escalators crisscrossing the interiors. […] Designers have fetishized the raw aesthetic of grain silos and factories in which form really is dictated by function.” This fetishization of industrial aesthetic is certainly reminiscent of Bauhaus and, therefore, of Modernism, only that in High-tech architecture, these industrial elements take the visual lead, whereas, in Bauhaus, the whole process of crafts and architecture was understood as a wholesome endeavor.

In the 1999 published book High techn?: art and technology from the machine aesthetic to the posthuman, R. L. Rutsky states further that the ‘“[h]igh-tech style, then, acknowledges this separation of technological form from function in a way that the modernist avant-gardes, with their belief in “functional form,” never could.

Thus removed or unsecured from their previous, functional context, these reproduced technological forms can be ‘reutilized’ as stylistic or aesthetic elements. Through this process of unsecured – that is, through technological reproduction – the conception of technology is itself unsecured; no longer chained to a notion of functionality or instrumentality, it comes instead to be defined in terms of a technological style, a high-tech ‘aesthetic.’”

The connection between High-tech architecture and functionalism is hereby not abandoned, only the forms do not directly translate to functions but rather, industrial and functional elements have been assembled into new forms, that, in themselves, become somewhat flexible and functional.

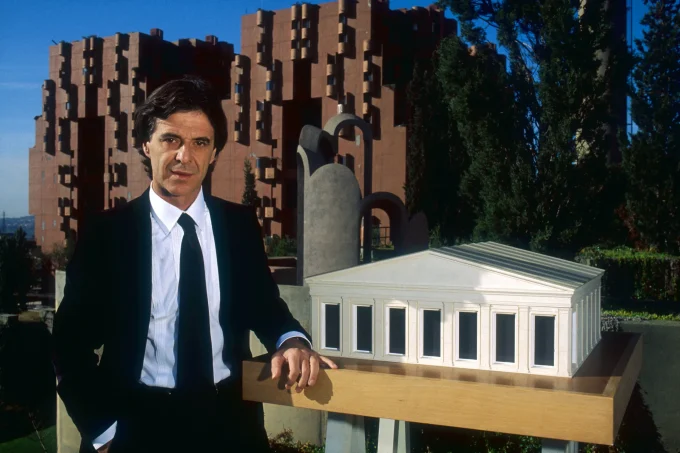

It is very clear where high-tech architects such as Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, Michael and Patty Hopkins, Nicholas Grimshaw, and Renzo Piano have drawn their inspiration from. In the article Revisiting the True Meaning of “High Tech” Architecture, Shumi Bose quotes Colin Davies and states that “in Britain, the ‘movement’ could be ascribed to individuals: namely, the buildings of the late 20th century designed by the likes of Foster, Richard Rogers, Michael and Patty Hopkins, and Nicholas Grimshaw.

The architects mentioned above set out an ebullient new frontier in British architecture, typified by the demonstrative use of metal and glass. Even the American architectural doyen Philip Johnson observed: “There isn’t anyone in America who can do something as good as the Sainsbury Centre. England has at once become the leader in the engineering and technology game.”

In reality, however, high-tech architecture is relatively far from the term high-tech as it is used in technological industries. In fact, high-tech refers to the aesthetics of a structure and references the progress of the time rather than being able to technologically adapt and master technical challenges. Rutsky notes that “[…] in fact, the appellation of “high tech” has been extended to items that seem to involve only the vaguest reference to anything technological.

When we find ‘high-tech’ used as an adjective for everything from track lighting to track shoes, it is obvious that the term does not refer to any particular notion of technological style but to a much broader sense of ‘cutting-edge’ aesthetics, of stylishness. High tech, in other words, refers to that stylistic ‘edge’ or ‘wave,’ to that technological process or movement in which elements are constantly abstracted, reproduced, and unsecured from their previous context: videotaped, digitized, altered, reassembled, recontextualized.”

Suddenly, importance is given to the object itself – an idea that references Modernism and its idea of the building as an object. Contrary to that, it also references the postmodern idea of a building that symbolizes something else and is eclectic in its stylistic elements. Nevertheless, in High-tech architecture, the building in itself becomes the facade for technology – without being highly technological (although, of course, also not primitive): The building conveys a message of science and progress.

To do that, architects have used the ideas of movement, motion, and transparency. As such, the architectural style seems most useful for public buildings – such as the Centre Pompidou or the San Diego Convention Center, which both use the shape of the building in their logo – but less for residential housing. The resulting spaces often have open floorplans and appear industrial, reminding easily of airports or supermarkets, which in that sense are still carriers of some form of High-tech design.

Frequently, however, such architecture can easily be misunderstood as a symbol of power and of the elite. Nevertheless, Heathcote from the Financial Times reminds us that “[…] the idea was quite the opposite: “The aesthetics of industry were marshaled as part of an effort to democratize architecture. Or at least that was the rhetoric. The argument went that the classical portico of the museum or the impenetrable concrete Brutalist boxes that had replaced them were symbols of an elitist, exclusive culture, and applying the language of industry would make these buildings part of the workers’ world; transparent, adaptable, determinedly nonhierarchical.”

But has high-tech architecture fallen out of its time? There are, of course, examples of this style even built-in more contemporary times, but they are nowhere near as archetypical as the older ones. It may be because, on the one hand, with ecological awareness, such aesthetic language may be hard to sell – who would buy an expensive-looking machine?

Carolyn L. Kane, in her recently published book High-Tech Trash Glitch, Noise, and Aesthetic Failure, states: “Impressive man-made developments in industry, architecture and public culture may dwarf individual agency, but if the earth is our collective household (whether we use the word “environment” or “ecology”), it is therefore also the home to which we all belong and share accountability for.”

On the other hand, High-tech architecture has not entirely disappeared, only our understanding of ‘high-tech’ has changed. Is not Apple Park, which looks as smooth as Apple products, one modern version of High-tech architecture? Is not CopenHill an ironic gameplay combining the idea of high-tech and fun? What has changed is that buildings nowadays are in themselves high-tech and smart whereas their design transports this idea to the outside.

Architecture is no longer only the facade of technology, but it is the technology itself: High-tech architecture becomes High-tech architecture. Beyond that, the technologies used and implemented are often less apparent and rather disguised. They may become visible through screens and media facades, in server rooms and data banks, in virtual reality, or in the metaverse.

With all this new technology in mind, the question then becomes again the same, that drove architects in the 1960s and 1970s: How can architecture reflect upon and provide for this technological progress? And similar to the 1970s, the answer might be in flexible, open spaces that are adjustable, perhaps rather minimalist and functional.

Leave a comment