Current Western cities do not fall short on technological, political, and social small-scale visions, but these visions are carried by the drive to capitalize and progress rather than by the desire to improve the quality of life for all. Technology is hereby seen as the panacea for improving the effectiveness of our lives, but in the process, essential questions are often not asked: Do we want to live in such a technotopia? How do we want to live in 30 years?

Seward ZM, Siraj Datoo. City of London halts recycling bins tracking phones of passers-by. © Quartz.

Utopias are collective pursuits, collective visions for a better future. The term goes back to the Greek ou-topos, meaning ‘no-place’ or ‘nowhere’, and was coined in Thomas More’s novel Utopia in 1516. Thankfully, the term ‘dystopia’ is much younger and was coined in 1886 by John Stuart Mill. It simply means ‘bad place’ and is often regarded as the opposite of utopia. Both words came into existence reflecting on existing political conditions – Thomas More on Catholicism in Britain, Mill criticizing the government’s Irish land reform. But instead of seeing these terms as opposites, they are rather complementary: A dystopia invites us to think about what we do not want and utopia invites us to think about what is currently missing.

In architectural history, there is no shortage of utopian visions: Already in 375 BC, Plato published sketches for a political utopian vision in The Republic centered around the question of justice – a vision that is for some the description of a totalitarian state. More famously, Le Corbusier’s famous plan of the Radiant City from 1924 similarly creates hiccups amongst urbanists. Fair to say, his vision of high-rise residential superblocks placed around a car-oriented infrastructure has been implemented in many European suburbs.

Ebenezer Howard’s plan of a Garden City from 1889 seemed more romantic, envisioning a detached work and home life with nutritious gardens (and clean air) for everyone. This plan was presented as an answer to the pollution and overcrowding that follows the industrial revolutions. Similarly, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City from 1935 sought to achieve that, a suburban plan completely ignoring any urban feeling and giving later urbanists such as Jane Jacobs cold sweats.

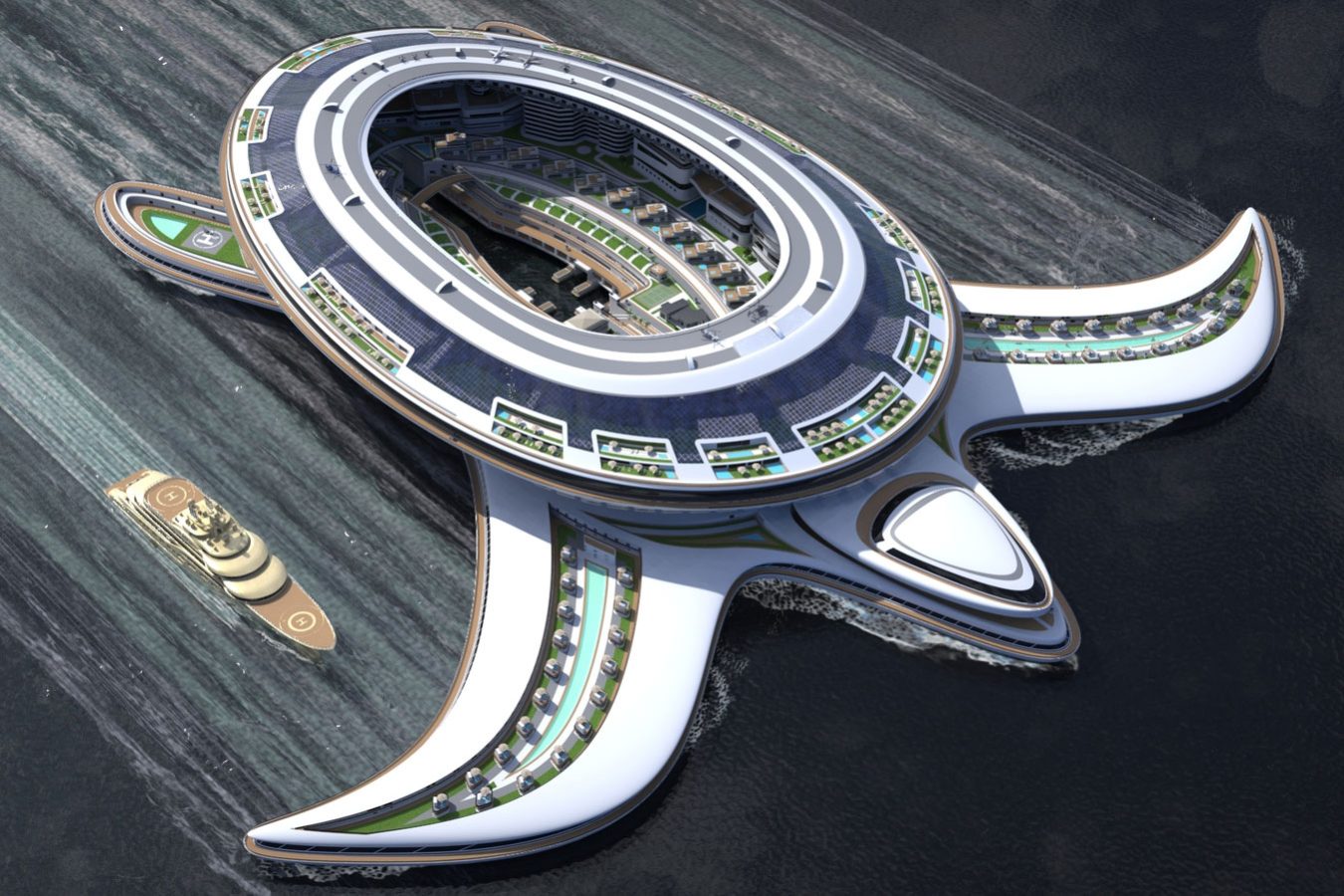

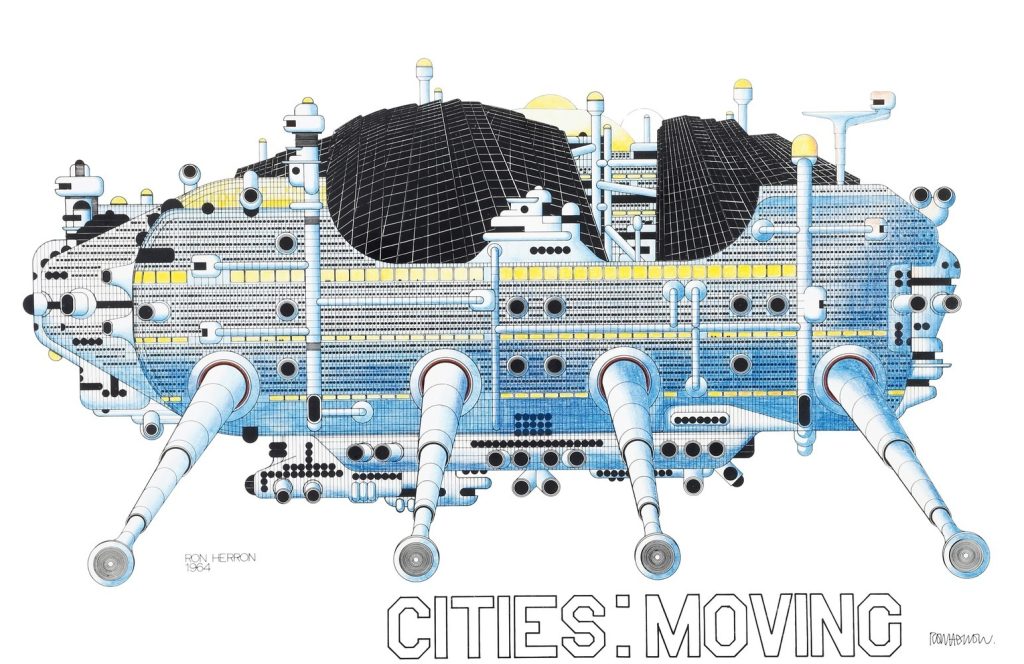

The other extreme is Mega-City One, an enormous post-nuclear metropolis of 800 Million inhabitants on the United State’s east coast. In this dystopian city from the comic series Judge Dredd, most inhabitants are unemployed and live in a highly urbanized multilevel space under a political dictatorship. But there are also more optimistic and contemporary visions: Archigram’s moving city may for some provide one, although unrealistic, answer to the needs of the current times. This city moves around wherever resources are.

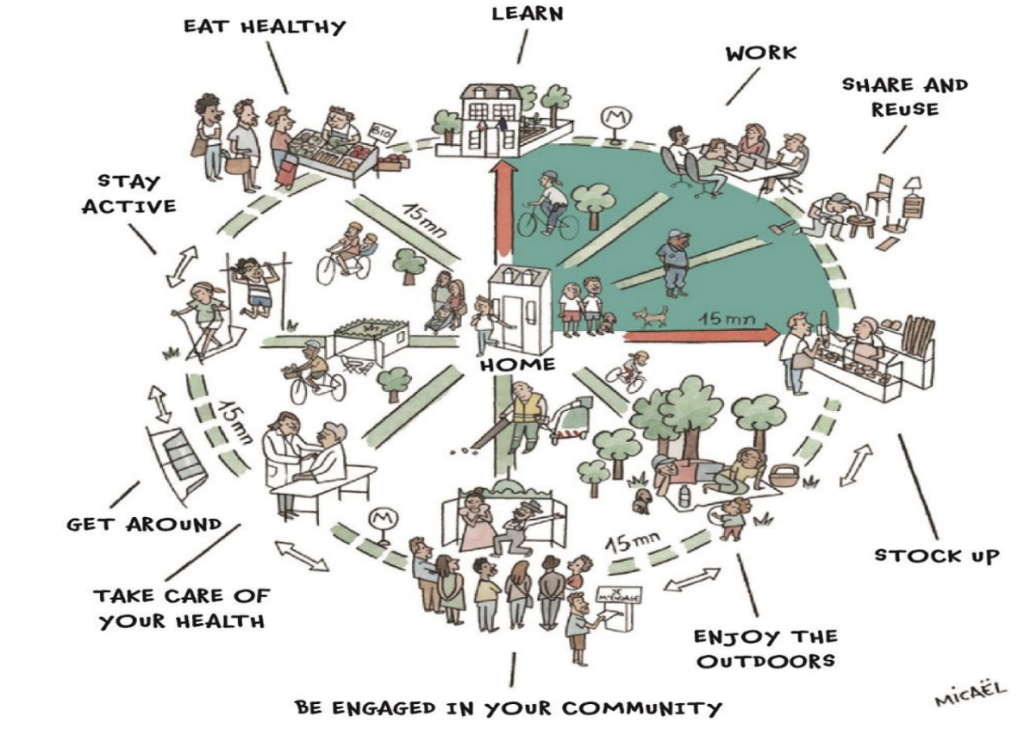

Also, Illdefons Cerdà’s 1856 plan for Barcelona is often mentioned as a success story of urbanism, only receiving accusations of being a gentrification accelerator. Lastly, the 15-Minute-City, coined in 2016 by the Sorbonne (Université de Paris) professor Carlos Moreno is a mostly local and sustainable project for European cities. The 15-minute-city essentially aims to meet everyone’s needs on a daily basis within a 15-Minute reach of one’s home. This, of course, has received much support from various local governments around the world during the times of Covid.

Nevertheless, it seems as if grandé visions which ignore any locality were always meant to fail, whereas small-scale and flexible solutions might be implemented. Mohammed Makki summarises this: “All too often the urban pattern was repeated blocks distributed across a grid with a little adjustment to the local ecology or environment. […] The problem with a city detached from its context – one that is generic, repetitive, and built around vehicle traffic – is that it resists adaptation. After all, it was not designed to adapt – it is “visionary”, a fixed solution to an ever-changing problem”. The other problem, a common trap for modernist architects, is to believe a certain spatial design ‘produces’ certain people.”

The list of utopian visions could go on, but the question I am raising is the following: How did we get from the Radiant City to litter bins that collect data, and do we need to get back? In a paper called Utopian Visions: Promise and Pitfalls in the Global Awareness of the Gifted, Don Ambrose states: “Some Utopian frameworks require individuals to subsume their identities into the collective. […] Other Utopian frameworks require individuals to become atomistic, separating themselves from the support and guidance of the community while concerning themselves only with their own needs and wants. Currently, dominant neoliberal ideology follows this pattern in its promotion and glorification of the atomistic, materialistic, self-aggrandizing individual. Both of these Utopian extremes, the disappearance of the individual into a machine-like collective and magnification of the atomistic, self-obsessed individual, run counter to the optimal development of the individual.”

It seems as if people create their own utopias and live toward and through them in their everyday lives. But is it not so that the issues and problems at stake are big enough to require the effort, visions, and participation of all people, a collective utopia? To name a few: gender equality, climate change, racism, wars and dictatorships, life beyond earth, economic hardship, and gentrification. And it is in the city that these problems will seem the most visible and feel the strongest. But it is easier to find a solution for oneself than to also find a solution for everyone. Additionally, the chances of someone’s utopia being someone else’s dystopia are high, so why even bother to include everyone?

“A utopia is a planned society; planned societies are often disastrous; that’s why utopias contain their own dystopias.”

– Jill Lepore in The New Yorker

To illustrate my argument, I will offer a more specific example, focusing on one specific topic: Climate change. The Line by NEOM is a project in Saudi Arabia that comprises a whole city in one line.

It is a smart city, it is sustainable, it is environmentally friendly, and it almost has no cars. The Line is a 170km long capitalistic and technological answer to climate change, building a city for One Million people from scratch instead of adjusting current cities to the needs of contemporary times. It is not difficult to imagine that this is a dystopian vision for some, precisely because the idea of terraforming and building from scratch seems to counteract sustainability and careful treatment of our planet, not even to mention the origin of the financial resources. However, on the flip side, there are other visions of a climate-friendly utopias: Community gardens, vegetarianism, cycling instead of driving, vacations in one’s countryside, and solar panels.

Both approaches aim at the same good, but perhaps not without tension between each other. In the book Urban Utopias: The Built and Social Architectures of Alternative Settlements from 2007, urban researcher Malcolm Mile writes that “[f]or a society founded on rationality and productivity, and the pursuit of pleasure in the display of identity, the presence of dystopian elements denied society’s realization of the ideal.”

In other words: How can I keep believing in my neighborhood’s cycle route if Saudi Arabia is terraforming a city? One answer to this can be taken from the very first work ever written on utopia by Thomas More from 1551: “T]he non-productive – the vagrant whose insecurity was produced by social change, like the thieves in More’s Utopia (dispossessed by land enclosures) – must be made invisible in a society embodying productivity.” In other words: To live toward one’s own utopia, one needs to ignore the wrongdoing of others.

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

– Unknown, often ascribed to Henry Ford in 1936

Here it may become more clear that whether Utopia is an actual place or a vision of living more equally and sustainably with others, utopias have always been a method. Frederic Jameson in the book Utopia/Dystopia – Conditions for historical possibility explains: “We ordinarily think of utopia as a place, or if you like a nonplace that looks like a place. How can a place be a method? Such is the conundrum with which I wanted to confront you, and maybe it has an easy answer. If we think of historically new forms of space – historically new forms of the city, for example – they might well offer new models for urbanists and in that sense, constitute a kind of method.

The first freeways in Los Angeles, for example, project a new system of elevated express highways superimposed on an older system of surface streets. That new structural difference might be thought of as a philosophical concept in its own right, a new one, in terms of which you might want to rethink this or that older urban center […].” Therefore, to answer my initial question, we have not lost Utopia. But a modern-day utopia is perhaps not a grandé masterplan to be followed by everyone but a gentle vision that each and every person follows and each and every city, architect, and policymaker implements to their own capacity.