Zaha Hadid (31 October 1950 – 31 March 2016) was a visionary architect, businesswoman, and teacher who left extraordinary works. She became the first individual woman awarded the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Hadid notices architecture as an art that deals with human emotional experiences like pleasure, happiness, etc. Her design inspiration comes from observing nature, people, and the city. In one of her interviews, Hadid said, “People ask ‘why are there no straight lines, why no 90 degrees in your work?’ This is because life is not made in a grid.”

Hadid won 93 prizes till 2012; the most important one is the Pritzker Prize (2004). Hadid’s first global recognition was in1982 with The Peak Leisure Club project in Hong Kong.

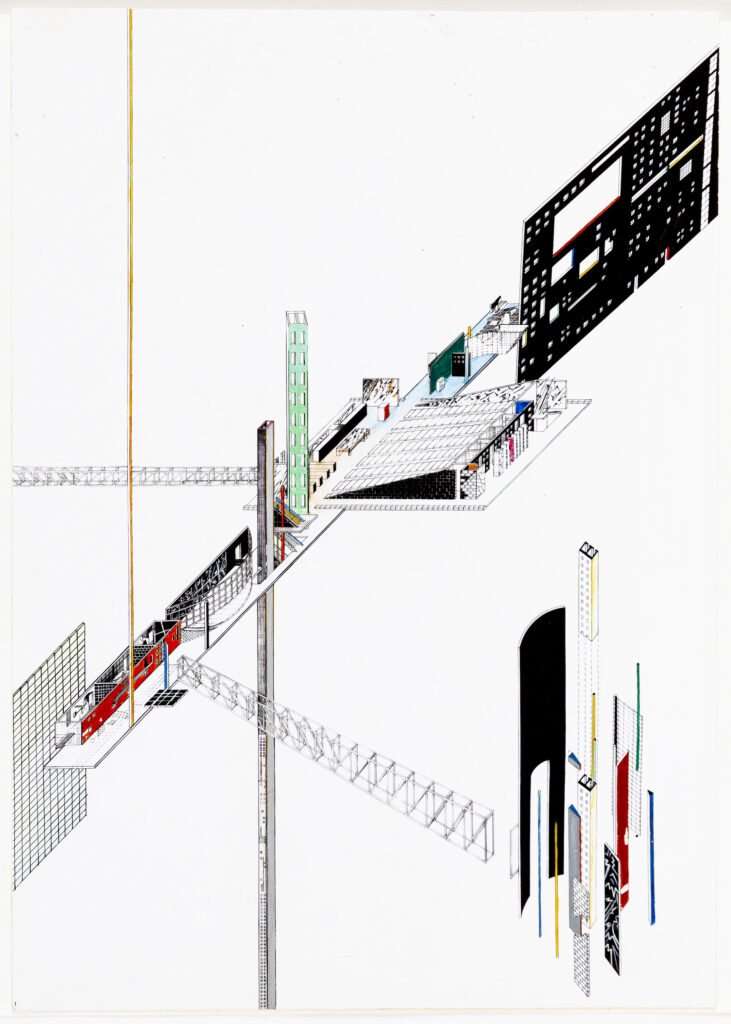

Drawing and painting had a primary place in Hadid’s practice. Hadid got closer to Russian Supremacist arts in the early 20th century when she studied Architecture at the Architectural Association School of Architecture after studying Mathematics at the American University of Beirut. Her early works were influenced by the suprematism of Malevich and the constructivism of Tatlin and Rodchenko. Hadid synthesized suprematism with the sections, plans, and isometrics of architectural drawing.

Hadid absorbed many constructivist elements into her architectural aesthetic. The most significant impact on Hadid’s art was Kazimir Malevich’s free linear dynamic construction style; she took geometrical elements and the anti-gravitational space of Russian avant-garde. This resulted in a new trend called Deconstructivism, characterized by antigravity, non-geometry, complexity, and fragmentation.

Hadid’s early works have been named dynamic Construction because of her methods’ dynamic, fragmentary form and combination. Dynamic Construction is the reference and creative development of the Russian avant-garde Suprematism and Constructivism in architecture.

Suprematism arts were built in time and space to portray a philosophical understanding of the world rather than simple aesthetic considerations. Constructivist practice broke free of the picture frame by using complementary methods.

New York-based architect Lebbeus Woods said about Hadid’s architectural practice, “Most architects make drawings. However, Hadid’s drawings of the 1980s are different in several ways. Most notably, she had to originate new systems of projection to formulate in spatial terms her complex thoughts about architectural forms and the relationships between them.”

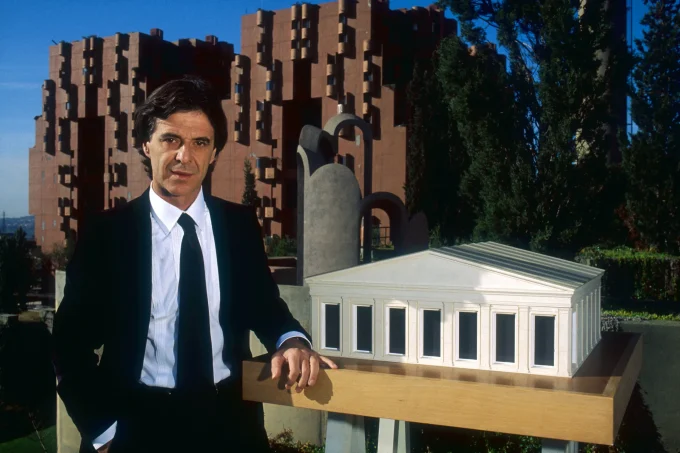

In 1988, the “Deconstructivism in Architecture” exhibition was held at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), New York, where seven architects participated; Coop Himmelblau, Peter Eisenmann, Thom Mayne, Daniel Libeskind, Bernard Tschumi, Frank Gehry, and Zaha Hadid. Deconstructivism was broadly divided into separate Derridean and non-Derridean.

Non-Derridean architects use a more realistic approach where concepts or ideas are taken from different sources; Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, and Frank Gehry were inspired by Suprematism, Constructivism, and nature, respectively, developing the form into a sculptural image and function following form.

Hadid took part in this exhibition with her architectural drawings. This exhibition was one of the critical steps for Hadid to announce her architectural aesthetic to the world. Malevich, Tatlin, and Rodchenko strongly influence these early paintings.

Lebbeus Woods recounted his amazement at Hadid’s painting techniques during a visit to her studio in 1984:

“I saw a watercolor Zaha Hadid was working on taped to a drawing board. It was a delicate and intricate drawing related to her breakthrough project for The Peak. Being one who drew, I asked her what brushes she used… Without a comment, she showed me a cheap paint-trim ‘brush’ that can be bought at any corner hardware store — a wedge of gray foam on a stick. I still remember my being shocked into silence. Years later, I understood her choice of tools as characteristic of her approach to architecture: a wringing of the extraordinary out of the mundane.”

Generally, she used calligraphic methods for visualizing her architectural ideas. The drawing was a design tool for Hadid, and abstraction was an investigative structure for visualizing architecture and its connection to the world around us.

On the other hand, technology and innovation have always been central to the work of Zaha Hadid Architects. Hadid used technology in her career but continued to do her hand drawings. She didn’t want her designs limited to what computers offered her. She said in an interview, “I don’t use the computer. I do sketches quickly, often more than 100 on the same formal research. The painting formed a critical part of my early career as the design tool that allowed us the opportunity for intense experimentation. The painting was always a critique of what was currently available to us at the time as designers – as 3D design software didn’t exist.”

Most of Hadid’s early works are theoretical, and she used the technique she developed at that time to construct these ideas in the future.

In 1992, Zaha Hadid was commissioned to create a collection of paintings and drawings for ” The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932,” a Russian Constructivism exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. This collection contains Zaha Hadid’s 32 ink drawings and 47 acrylic paintings.

Hadid recreates Malevich’s “Tectonic” as a “bent” form and uses color in a manner reminiscent of Theo van Doesburg and members of De Stijl. Also, Hadid was the first architect who had the opportunity to design an exhibition in the Guggenheim Museum. She separated the Guggenheim into thematic interventions: Bent Tektonik, Black Room, Globe Room, Maze Room, Porcelain Beams, Skyline of Tektoniks, Suprematist Walls, Tatlin Tower, and Zig Zag Wall.

Hadid reflected on the influence of artist Kazimir Malevich on her work in an article in the Summer 2014 issue of RA Magazine:

“One result of my interest in Malevich was my decision to employ painting as a design tool. I found the traditional system of architectural drawing to be limiting and was searching for a new means of representation. Studying Malevich allowed me to develop abstraction as an investigative principle.”

At the same time, Hadid finished the “Vitra Fire Station” in Weil am Rhein, Germany, one of the important works from her early career. It is also the first time Hadid transformed her vibrant and experimental two-dimensional images into three-dimensional architecture. The building is also notable for the way it points and extends; it appears to expand and lengthen space itself, both on paper and in the façade.

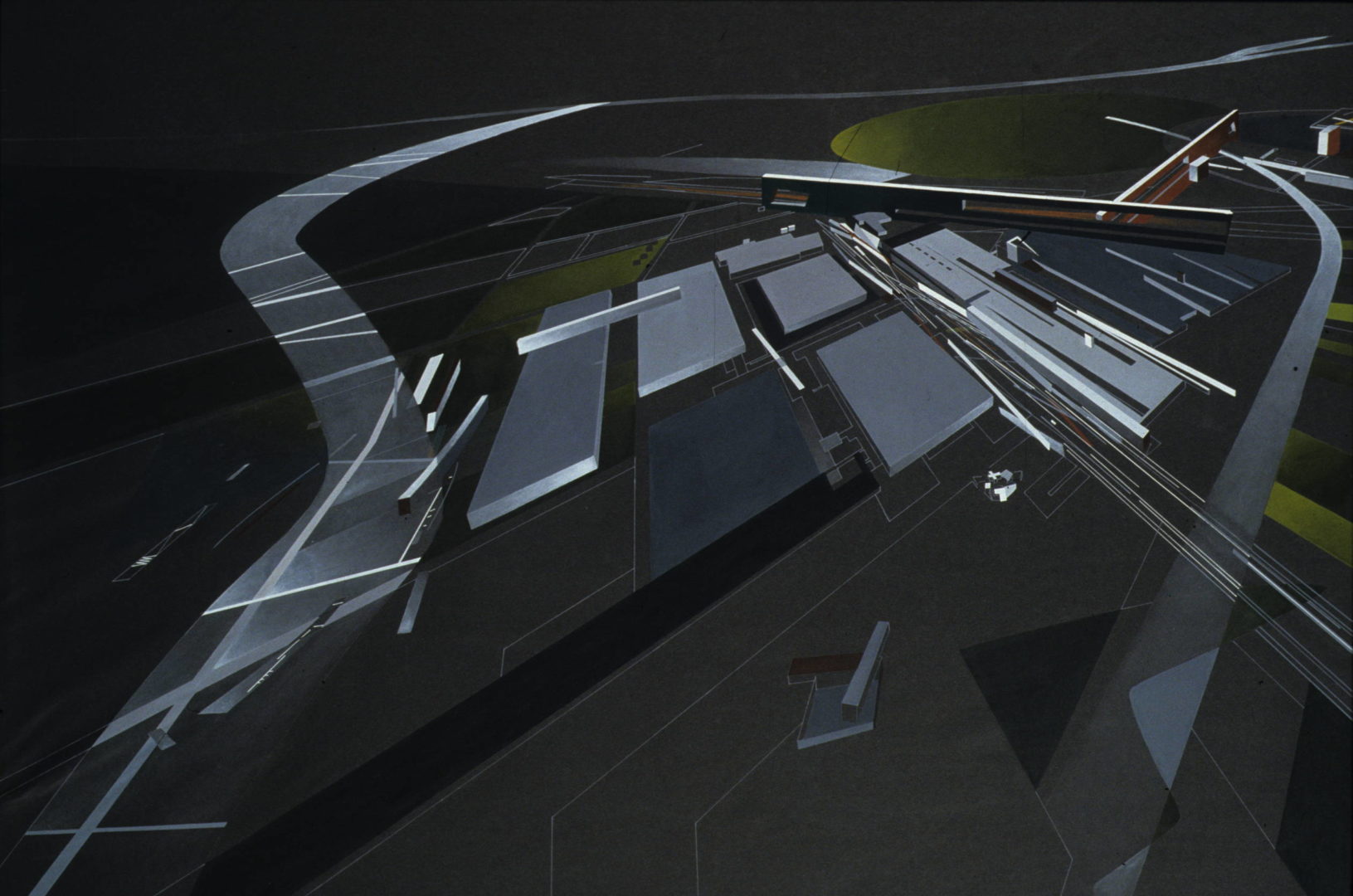

It is not always easy for Hadid to have her ideas built, despite her becoming an architect known to all of us. Another project where we can see other lines inspired by Malevich: The Peak in Hong Kong (1983). The project idea won the competition but was never built. The works are composed of deconstructed volumes that have exploded into a series of razor-sharp components that project outwards indefinitely.

Hadid’s daring composition produced a building with a sense of tension and movement. Still, it also serves a practical purpose: its multifaceted exterior allows for multiple entrances and exits for firefighters and vehicles. This emphasis on fluid motion can be seen from the first painting to the finished fire station.

We can add a lot to this article about Zaha Hadid’s designs, drawings, and inspiration for the world of architecture. We remember Hadid’s inspirational works on her birthday and on the 6th anniversary of her passing.

Learn more about Zaha Hadid Architects’ 10 Noteworthy Works Of Zaha Hadid (ZHA)

Learn with PAACADEMY: Attend workshops at PAACADEMY to learn from the industry’s best experts how to use advanced parametric design tools, AI in design workflows, and computational design in architecture!

Leave a comment