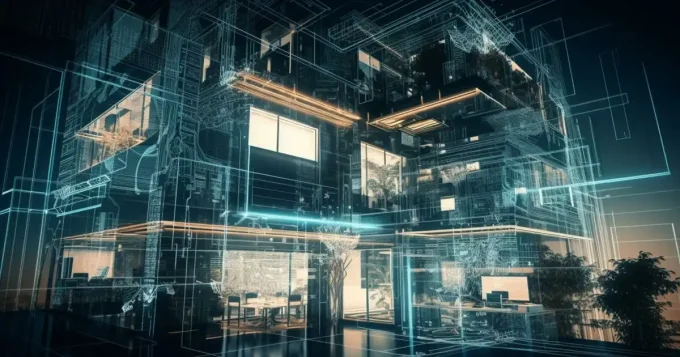

This is how generative design is changing the very landscape of architecture, borrowing what nature has had time to test in its efforts to construct perfect worlds – particularly through the instruments of biomimicry. This involves taking the best nature has had millennia to perfect in structural efficiencies and applying these to the buildings created by human innovation, making them aesthetically pleasing yet strong, sustainable, and highly useful. Biomimicry, which looks for answers from nature, provides the foundation on which generative design algorithms are based, thus producing designs that are responsive to the complexities of real-world environments.

Eastgate Centre: Biomimetic Design for Sustainable Cooling

The best example of a biomimetic generative design is probably the Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe. It is a commercial building designed by architect Mick Pearce, emulating the self-cooling mounds built by African termites. These termites, therefore, ensure stable temperatures inside their mounds despite the extreme fluctuations outside. These principles of theirs, Eastgate Centre emulate and use only a fraction of the energy consumed by HVAC systems. Amongst its peers, it is one of the pioneering examples of sustainable architecture. This type of biomimicry demonstrates how, by applying generative design, energy-efficient solutions in harmony with the environment can be engineered.

Computational technology is at the core of this approach. Generative design can work with algorithms to come up with a set of variations of designs based on specific parameters, such as material efficiency, structural strength, and environmental responsiveness. Algorithms can process large inputs of data, and perform simulations that foretell how a structure might behave through time. This is how generative design can maximise structures to both be resilient and resource-efficient. Such software includes Autodesk’s Fusion 360 and Bentley’s Generative Components, which allow the designer to input parameters and then to let the software generate forms that wouldn’t necessarily be possible with the old design process.

Resilient Design in ZHA’s Generative Structures

Generative design structural forms are usually intricate and organic, with a visual appeal reminiscent of organic natural phenomena. For instance, the design of the Morpheus Hotel by Zaha Hadid Architects in Macau was inspired by a structure based on a bamboo shoot and ended up looking like an exoskeleton that interlinks with each other to optimize the load distribution and stability. These exoskeleton structures are very common within plants and lightweight biological organisms as they minimise the need for the existence of internal supports while maintaining strength. The Morpheus Hotel not only shows the aesthetic value of biomimetic architecture but also shows how generative design can lead to resource-saving structural efficiencies.

Biomimicry and generative design are playing critical roles in improving building resilience to natural disasters. For instance, the Form Finding Lab at Princeton University is researching how the skeletal structures of sea sponges can inspire designs that make buildings earthquake-proof. Through the pore lattice structure of a sponge’s skeleton, computational models were developed to maximise strength and flexibility in building materials for absorption and dissipation of seismic energy. This approach illustrates how nature’s evolutionary adaptability can be informative and advance our sense of architectural resilience.

Biomimetic Design for Self-Healing Structures

A strong appeal of biomimetic generative design is that it lends itself to sustainable material use. For instance, in the area of bioconcrete—a material that replicates the healing processes that are present in some organisms—the science of creating self-healing buildings has been moved forward. Bioconcrete contains bacteria that react when water hits them to produce limestone, so this material can fill in minor cracks over time and extend a building’s lifespan. This material, developed by Dutch scientist Henk Jonkers, minimises concrete waste and the need for frequent repairs while operating on a low-maintenance, almost nature-inspired solution to concrete inspiration from nature’s resilience.

Smart Biomimicry: Generative Design for Urban Ecosystems

Applying generative design tools with biomimicry is changing not only the exterior of buildings but also the internal environments in which we live or work. For example, on the Milan-based project “Bosco Verticale” (Vertical Forest), architect Stefano Boeri added generative design principles to over 20,000 plant integrations of two high-rise buildings. This generates a unique ecosystem within an urban space that also improves air quality, fights noise, and controls temperature. This generative design, inspired by the silhouettes of forest ecosystems, reflects the power of adaptive, biophilic architectural styles to improve life in cities.

Biomimicry-based generative design is on the cusp of artificial intelligence and machine learning research. If architects apply it together with generative design software, they can go further in updating the actual solutions based on real-time environmental input. For instance, AI-enabled sensors in smart buildings may track light, humidity, and temperature to change a building’s systems to optimize energy use. It is possible that these “smart” generative designs will become regular for urban planning areas where adaptability at a moment’s notice would play a huge part in sustainability.

These developments also challenge the role of human ingenuity within the process of designing. In the generative algorithm generating an infinite array of forms, architects serve as curators selecting and refining forms best suited to aesthetic and functional goals. This synergy between human intuition and computing power represents a new era in design where technology amplifies, rather than replaces, human creativity.

Circular Design: Biomimicry and Generative Architecture

Biomimicry in generative design comes hand-in-hand with general principles for circular economy towards sustainability and resilience. In studying an ecosystem where the waste is recirculated and reused, architects will be able to work on buildings that are all part of a closed-loop system but manage to bring down their footprint on the earth. One of the prime examples of this principle is the “Circular Garden” installation of Carlo Ratti Association. This structure is totally biodegradable, melting back into the earth after use because it was designed from mycelium, a fungally grown material. I’ll find this to be an exceptionally nice aspect of the use of organic material in architecture-being capable of bringing about fully regenerative architectural solutions.

Because of generative design and biomimicry, there is an implication of a step into architecture symbiotic with nature: buildings are no longer static structures but are dynamic systems in their own right. In the face of an increasingly intertwined range of global challenges-from climate change and lack of resources to rapid urbanisation-this approach to design will be more propitious for resilient, adaptive buildings that can be designed to meet the needs of future generations.

Biomimetic generative design does not mean only copying the aesthetics of nature but rather reflecting its principles for adaptation, efficiency, and resilience. The future of this frontier is likely to shape the structures we build, making them more and more deeply intertwined with the world around them, creating a built environment that respects and thrives in those ecosystems in which it occupies.

Staying Ahead with PA Academy

For those decision-making mastering the cutting-edge tools shaping the future of architecture, check out PA Academy for a wide range of workshops on VR, AR, and other digital design tools. Their expert-led sessions provide hands-on experience and insights that can help architects and designers stay at the top of their game in an ever-evolving industry.

Leave a comment