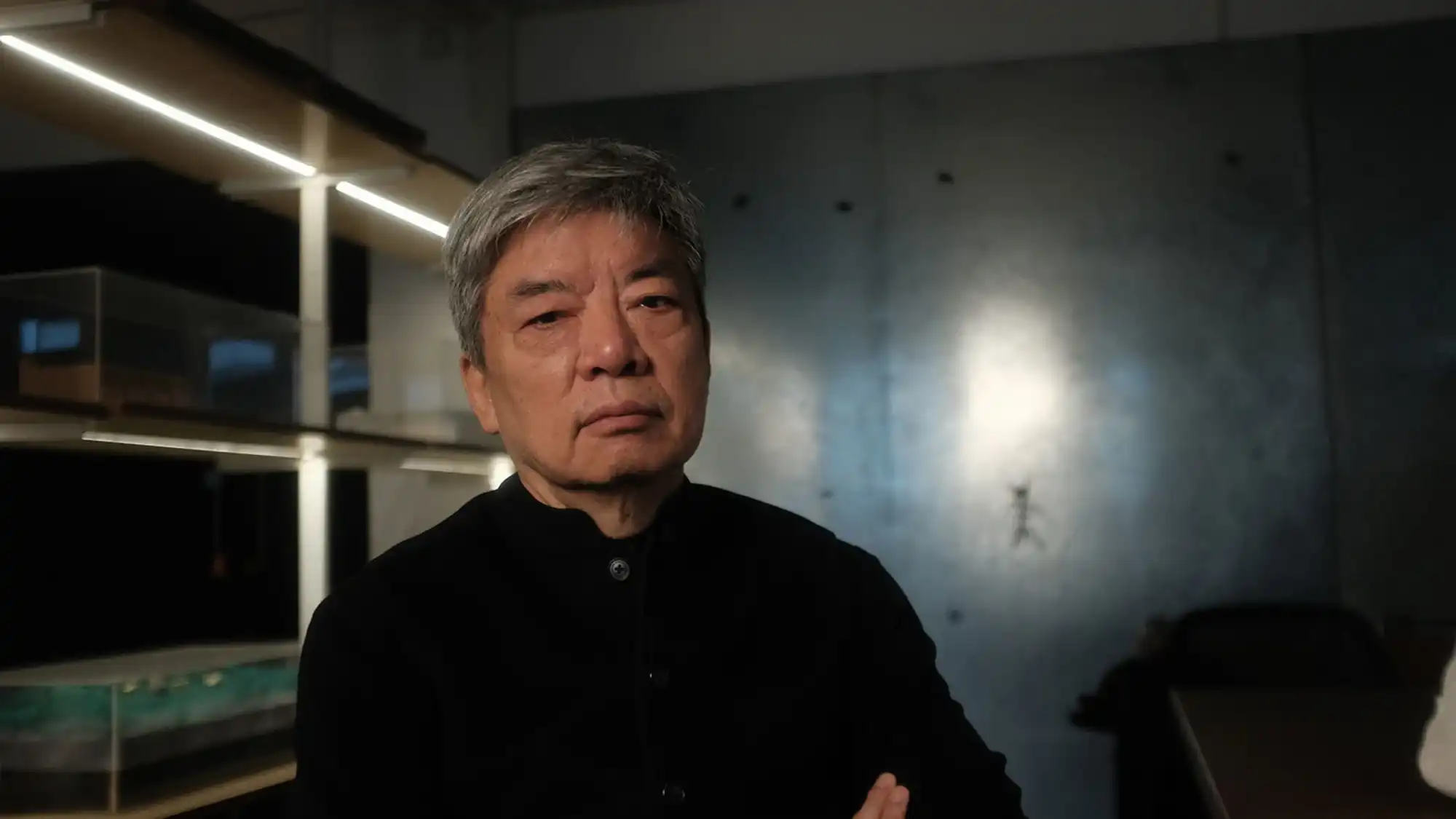

The Latest Pritzker Laureate, Liu Jiakun, is a Chinese Architect, in fact, only the second Chinese Architect after architect Wang Shu in 2012 to receive this prestigious prize. Liu Jiakun was born in Chengdu in 1956, grew up in this dense urban city, pursued a Bachelor of Engineering degree in Architecture at the Institute of Architecture and Engineering in Chongqing, and graduated in 1982.

After his graduation, he worked at the Chengdu Architectural Design and Research Institute, but he found that his interests lay in writing. Subsequently, he moved to Xinjiang and fully indulged in painting, writing, and meditation. However, an exhibition he attended in his 40s persuaded him to revisit architecture and open his own practice in 1999.

Since then, Liu Jiakun has worked on a variety of projects, from institutional buildings to urban-scale developments. Some of his notorious works at an urban scale include the Songyang Culture Neighborhood and the renovation of the Tianbao Cave District of Erlang Town. The Chinese Architect has also worked on several museum projects, including the Luyeyuan Stone Sculpture Art Museum, which was his first project, the Museum of Clocks in the Jianchuan Museum Cluster, and the Suzhou Museum of Imperial Kiln Brick.

Below is a selection of a myriad of the Pritzker Prize Winner Liu Jiakun’s works. To understand more about the Pritzker Prize Laureate, his bio, and his design philosophy, read more at 2025 Pritzker Prize Winner Liu Jiakun, a Chinese Architect Who Combines Utopia with Function.

The Renovation of the Tianbao Cave District

Location: Erlang Town, Gulin County, Luzhou City, China

Scope/Program: Urban Scale Renovation

Year: 2020

Actually, the site leveraging the natural liquor storage caves in the surrounding and the Chishui River’s ability to make good liquors served as China’s renowned and established Lang Liquor’s production zone. The project’s main aim was to construct new buildings instead of the dilapidated old ones and connect them to the other old buildings scattered on the site.

Sitting on a picturesque site – the central part of the cliff right below the Tianbao Peak, near the Chishui River basin, and Tianbao, Dibao, and Renhe Caves, the renovated ‘pan museum’ creates a subtle impact. The design seems to sit sturdy on the mountain, blending with its backdrop, and float simultaneously, due to the red roof overhangs mimicking the typical Chinese pavilions. Incorporating juxtaposing ideas together in design is a part of the 2025 Pritzker Prize Laureate’s design philosophy.

With scattered components, projects employ a literary narration strategy to weave the disparate components into a complete continuous spatial experience with the help of multi-level plazas and terraces. The journey begins at a 60-meter-long green entrance tunnel made of composed steel and bamboo, connecting to the reception hall via the project’s signature plank walkway and lounge bridge. Again, through the signature landscaped walkway, the visitors arrive at the Poetic Liquor Yard.

From the Poetic Liquor Yard, a cluster of The Tree Yard, Exhibition Hall of Lang, Liquor Tasting Pavillion, and Blended Experience can be accessed, which culminates in the Terrace Garden. The striking feature of this project is the sloped elevator that connects the visitors to the Cliff Restaurant and Renhe Cave.

West Village

Location: Qingyang District, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Scope/Program: Urban Complex

Year: 2015

The site covers a massive area of an entire block spanning 237 meters from east to west and 178 meters from north to south. The site actually hosted a golf course and a natatorium earlier, out of which the natatorium on the north was preserved and repurposed into a multifunctional center by Liu Jiakun in the West Village project.

Understanding the zoning and urban development regulations provides insights into the constraints that the West Village project was subjected to. The site, surrounded by high-rise communities, was set aside for community sports activities with a maximum plot ratio of 2.0, 40% site coverage, and a maximum allowable height of 24 meters.

Liu Jiakun saw the potential to develop an urban complex with public spaces, commercial spaces, sports and recreation spaces, and leisure spaces all together in this humungous plot with a traditional Chengdu character and contemporary configuration. The architect designed a building spanning 182 meters from east to west and 137 meters from north to south, five to six stories high, with an additional two levels underground along the periphery of the plot, leaving the central space green and open for communal and recreational activities.

The east, west, and south are dense with commercial spaces with balconies overlooking the street side and inner courtyard. On the north side, the openness of the courtyard is interrupted by the rehabilitated natatorium. However, the designers cleverly sought the issue with the hallmark feature of this project, the crisscross ramp tracks, approximately one and a half kilometers long community and recreational track, that connect the levels of the urban complex.

The inner courtyard features stadiums, various bamboo yards, and a smaller inner track. The inner courtyard is an embodiment of the Chengdu landscape design of tea houses and bamboo spaces. The stadiums are in the inner area of the smaller track while the bamboo yards that feature a variety of bamboos flank the outer edge of the inner track. These bamboo yards are equipped to serve as bamboo classrooms, bamboo workspaces, and bamboo tea houses. Under the track, supporting facilities and a Gallery are housed.

Novartis Shanghai Campus – Block C6

Location: Shangai, China

Scope/Program: Commercial (Office)

Year: 2014

The C6 building in the Novartis Shanghai Campus was designed by Liu Jiakun to house the laboratories and office spaces. It is a 31-meter-tall, 6-storey building with two additional underground levels. As Liu Jiakun prioritizes both collective spaces and individual spaces, the C6 building was designed mainly with an open-plan layout but also housed smaller private meeting spaces.

In addition to the main office spaces, the architect has injected communal spaces in the design that foster unplanned meetings and social interaction, improving the communication and efficiency of the employees and company culture. Fulfilling this idea, the architect inserted a large open courtyard on the ground level, and an atrium space flanked by a green living wall and staircase. The wrap-around veranda on every level also caters to this idea.

The distinguishing feature of the Novartis Shanghai Campus’s C6 building is its cantilevered wrap-around verandas that appear like protruding eaves pay homage to the Classical Chinese Towers and resemble them. Operable rotating laminate bamboo louvers that allow for daylight optimization installed on these verandahs are also inspired by top-hung windows found in traditional Chinese homes.

Museum of Contemporary Arts (MOCA)

Location: Chengdu, China

Scope/Program: Museum

Year: 2011

The project site was fairly mediocre, surrounded by high-density residential and commercial towers and monotonous office buildings. An IT Park, high-rise housing, and office buildings are the immediate neighbors of the project. The site clearly lacks depth, due to the absence of humane surroundings encouraging a social life.

Liu Jiakun is praised for his ability to design spaces that serve as buildings, infrastructure, landscapes, and public spaces simultaneously. The architect is notorious for finding space in dense urban environments and inserting a collective space in individual spaces. This site gave the perfect opportunity to harvest this practice of the architect.

This specific project was designed as a civic core in an otherwise dry urban landscape, making the landscape design the striking feature of the project. The main mass of the project is broken into boxes and is spread on the edges of the site, leaving a depression in the middle that resembles a V-shape in elevation.

The depression is achieved with sloping roofs and stairs that provide access to the upper floors. This dip serves as a social condenser on the ground floor interface in contrast to the surrounding high rise towers. The configuration of this feature accentuates its role as a public space drawing the attention of the passerby.

Hu Huishan Memorial

Location: Anren Town, China

Scope/Program: Memorial

Year: 2009

Unfortunately, the Sichuan Wenchuan earthquake in 2008 cost the lives of over 58,712 people, out of which 5335 of them were students. Hu Huishan, a 15-year-old girl, also passed away due to the tragic event on May 12, 2008. The Hu Huishan Memorial was built in honor of Hu Huishan and intends to acknowledge the entire nation’s mourning in the aftermath of the earthquake.

This modest, barely 52 square meters huge memorial hall is nestled in a lush green landscape. The structure is quite simple, mimicking temporary relief tents, but it is built in durable plaster and left unpainted from the outside, reflecting the pain and agony. However, the interiors were well-lit and painted with a particular shade of pink that was Huishan’s favorite.

The public was not allowed inside, but they could view through a peephole to see the empty stool that caught their attention due to the light that the roof opening cast on it. The hall housed other possessions of the young girl in the interiors.

Clock Museum of the Cultural Revolution

Location: Chengdu, China

Scope/Program: Museum

Year: 2007

The Clock Museum of the Cultural Revolution is one of the 30 museums in the Jianchuan Museum Cluster in China, established by Mr. Fan Jianchuan. This museum embodies Liu Jiakun’s philosophy of blending seemingly contradictory ideas like history and modernity, collectivism and individual expression, utopia, and realism.

While culture and economics are viewed as the opposing ends of the spectrum, they coexist in Jiakun’s Clock Museum’s design. Through his unique design approach, Jiakun addresses the major problem of the economic viability of museums and provides an innovative yet efficient solution by designing the Clock Museum of the Cultural Revolution.

Inspired by a practice in ancient China that allowed the establishment of stalls selling incense sticks and snacks on the outskirts of Chinese temples, the architect designed tranquil temple-like interiors for exhibiting and open-air spaces around the museum for food vendors to open up shops, attracting visitors and ensuring commercial success. With the implementation of this idea, the bustling exterior,s in contrast with the serene interiors of the Museum exhibition halls, resemble the experience from outside to inside felt while entering temples.

The Museum is arranged on a central spine as a passage connecting the three disparate exhibition halls. The first hall is a rectangular apse-ended memorial hall that displays the statue of Deng Xiaoping, emphasized by the skylight above. The sweeping curves in the museum space offer plenty of space for contemplation and reflection. Further, the columbarium featured on the walls of the third exhibition hall of the museum, traditionally built to store cremation urns, contains an array of clocks that symbolically press the end of the Cultural Revolution.

The Sculpture Department of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute

Location: Chongqing, China

Scope/Program: Institutional

Year: 2004

The Sculpture Department of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute is another testament early in Liu Jiakun’s career that displays he is like water and doesn’t work with a preset but churns out an opportunity on-site addressing the constraints. The teaching building was situated at the corner of the campus on a narrow plot.

However, the brief required larger spaces than the ground floor footprint. The Chinese Architect came up with a playful interesting solution of enlarging the footprint of the upper floors, giving the appearance of protruding layers.

This is one of the few projects designed by Liu Jiakun which displays depth in terms of form with narrow ground floor, larger upper floors, perforated walls, and recessions in the fourth and fifth floors of the building.

Owing to the harsh hot and humid climate of Chongqing and illumination needs as per the brief, the designers have adopted double-layered perforated walls on the west and south facades to optimize lighting and natural ventilation. .

What does the 2025 Pritzker Prize Winner, Liu Jiakun, express?

The Chinese Architect winning the Prtizker Prize, known as the ‘Nobel of Architecture’ this year, expresses that he doesn’t follow a particular style. And indeed, it is clear from the approaches that have shaped his projects above.

“I always aspire to be like water,” says Liu, “to permeate through a place without carrying a fixed form of my own and to seep into the local environment and the site itself. Over time, the water gradually solidifies, transforming into architecture and perhaps even into the highest form of human spiritual creation. Yet it still retains all the qualities of that place, both good and bad.”

Do you agree with the Architect’s statement?

Leave a comment