Michael Graves (1934–2015), one of the most prominent architects of the late 20th century, is well-known for his contributions to Postmodernism. Graves promoted colourful, textural, and ornamental designs that deliberately restored aspects that Modernism had fiercely rejected. This was also an outright rejection of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more,” to which Graves famously said, “less is a bore”. By designing places that were practical and emotionally impactful, he aimed to close the gap between abstract theories and the real-world human experience. According to Graves, structures ought to communicate with people; they represent memory, culture, and narrative.

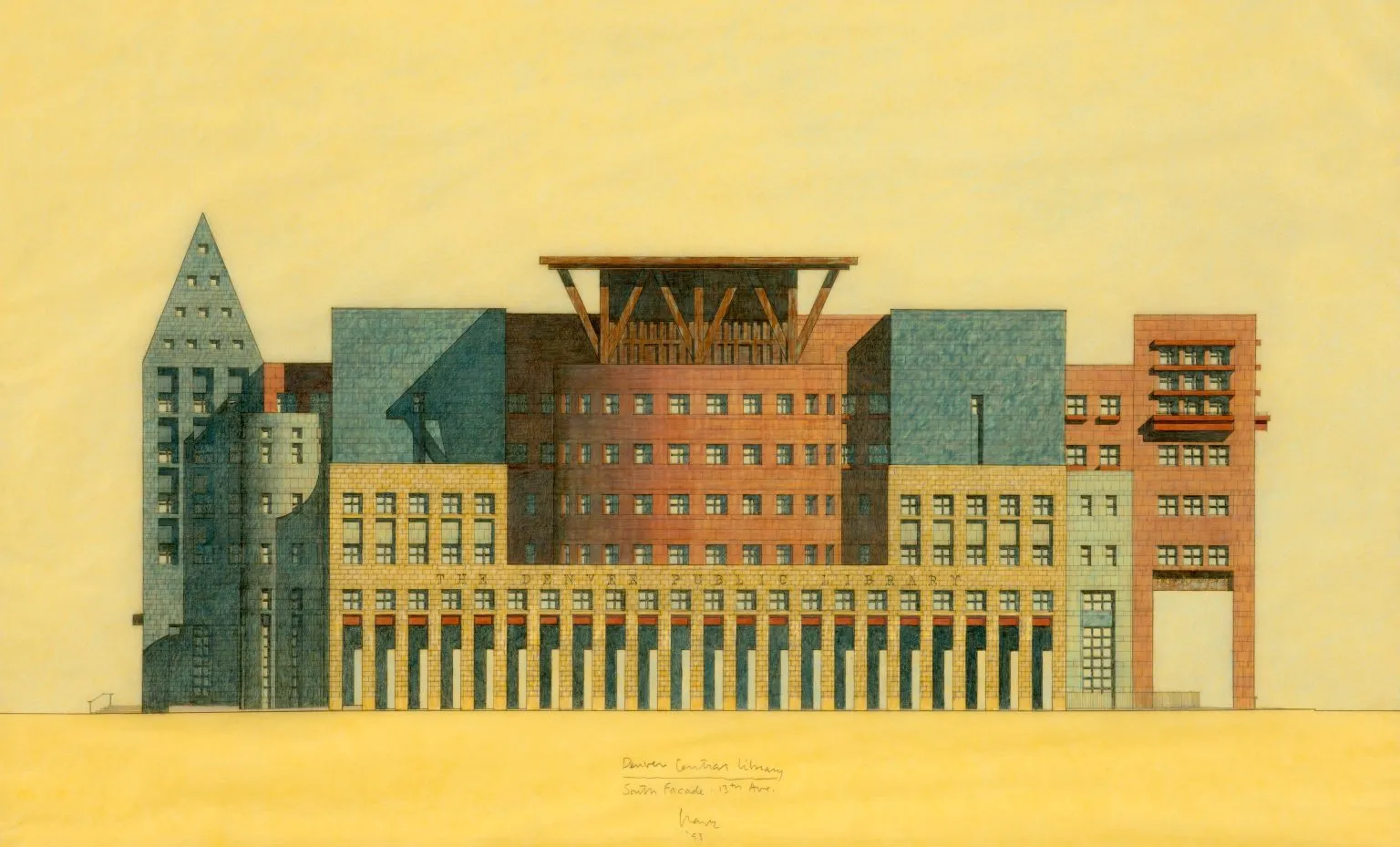

The 1995 completion of the Denver Central Library reflects Graves’ philosophy and is a monument to his principles. The Denver Central Library was created in partnership with the Denver-based firm Klipp Colussy Jenks DuBois. More than a library, it is a civic place that connects with the history and urban fabric of the city. His philosophy that architecture should be both accessible and meaningful is embodied in the Denver Public Library’s complex shapes and symbolic detailing.

Postmodern Era: Denver Public Library by Michael Graves

Prior to Michael Graves’ intervention, Burnham Hoyt‘s 1956 Modernist building served as the home of Denver’s Central Library. By the 1990s, the city was looking for an enlargement that would make room for expanding collections and make the public area more inviting. Graves’ winning design weaved the old and the new, preserving the historic structure and adding a beautiful new wing.

The library is a cultural hub that connects the city’s business core and Civic Centre Park in downtown Denver. The design reinforces the library’s status as a public icon by using eye-catching sculptures and honouring the urban grid.

A Masterpiece by Michael Graves

Graves’ Denver Library is a masterwork of postmodern architecture, combining geometric shapes, classical allusions, and vivid hues to produce a structure that is both imposing and hospitable. Important characteristics include:

The Entrance

The gold-domed rotunda, which acts as the library’s great entrance, is the most recognisable feature. In a subtle tribute to Colorado’s indigenous past, the dome, which pays homage to classical civic architecture, is adorned with a design inspired by Native American basket weaving. Graves’ view of architecture as a storytelling medium is reflected in this combination of native and Western influences.

Facades and Massing

Stepped terraces, cylindrical shapes, and rectangular blocks interact dynamically to create the building’s massing. The exterior creates a strong textural contrast by combining metal highlights and stucco with red sandstone, a local resource. The continuity of architectural communication throughout time is reinforced by sized windows, some of which are arched and others square.

Human Experience

Instead of creating an open-plan Modernist hall, Graves planned the library’s interior as a network of connected “rooms.” With reading nooks surrounded by arches, columns, and vaulted ceilings, this design encourages closeness and exploration. The area feels more human scaled and less institutional owing to the use of warm wood, terrazzo floors, and natural light.

Ornamentation and Colour

Graves welcomed colour as a means of communication, in contrast to the stark grey of Modernist libraries. The Denver Library’s ochre, deep red, and blue colour scheme, together with ornamental features like friezes and murals, strengthens the building’s municipal character. These elements engage visitors’ senses and minds, ensuring that the structure feels alive.

Denver Public Library: A Community Hub

The Denver Public Library is noteworthy for its urban function in addition to its architectural qualities. By linking the historic Civic Centre with the Denver Art Museum and the surrounding communities, the design restored an important civic node. While the library’s expansive steps and plazas encourage public use and involvement, its imposing tower acts as a visual antithesis to Gio Ponti’s Denver Art Museum from 1971.

Graves recognised that a library serves as a cultural hub in addition to being a storehouse of books. Through its hospitable entrances, incorporation of public art, and multipurpose areas that support performances, exhibitions, and educational initiatives, his architecture serves this function. The structure extends the concept of democracy into the fabric of the city by engaging with it and not standing apart from it.

Criticism and Legacy

Michael Graves’ design was initially criticised by some who thought it was excessively ornamental or out of line with Denver’s less extravagant architectural designs, despite being acclaimed for its daring style. But as time has passed by, the library has grown to become a cherished icon, proving that postmodernism can provide significant public areas.

The Denver Central Library is a shining example of postmodernism’s goal to design architecture that is meaningful and speaks to humans. The rigour of Modernism is rejected in favour of a colourful, multi-layered composition that is visually pleasing and encourages interpretation. Through the construction of the Denver Public Library, Michael Graves conveys that architecture ought to be a paradoxical art form that celebrates ambiguity while relating to the occupants. The Denver Public Library, which was completed almost thirty years ago, is still a notable civic landmark and a successful example of Michael Graves’ architectural philosophy.

Leave a comment