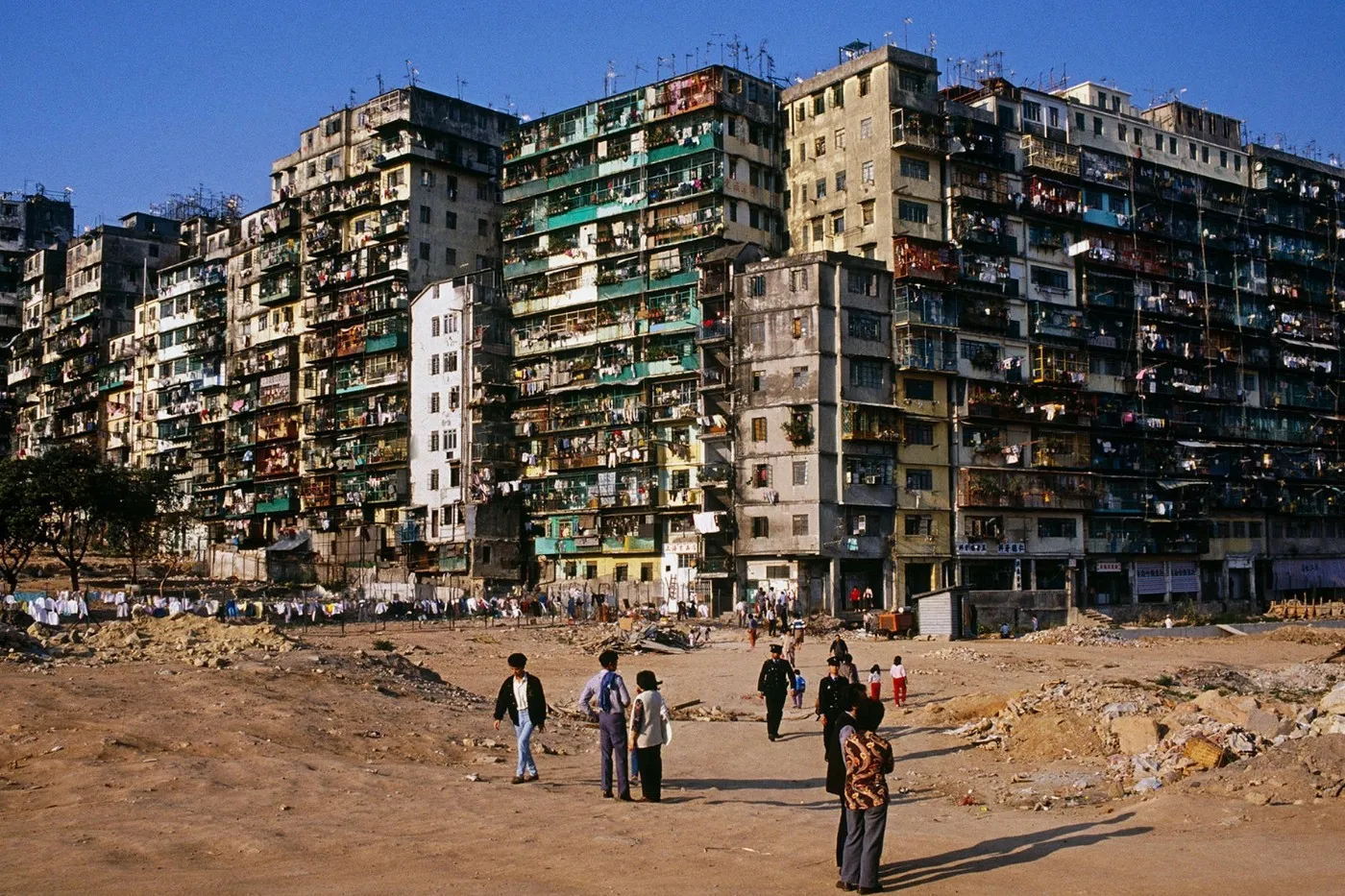

Kowloon, a city within a city, resembled a vertical slum. The city was a towering jumble of interconnected buildings, with some rising as high as 14 to 15 stories. The structural integrity of these buildings was often questionable, with ad-hoc additions and alterations that defied any conventional understanding of urban design. Apartments were tiny, with little room for privacy, and often multiple families shared one unit.

The architecture of Kowloon was an architectural anomaly born out of necessity and a complete absence of formal urban planning. Still, despite the challenging living conditions, a strong sense of community existed within the Walled City. Residents formed close-knit social networks, and small businesses, including restaurants and markets, thrived within the city.

As an architect, Kowloon, the Walled City that once existed within the bustling urban landscape of Hong Kong, has long fascinated me. In recent years, MCW architects have had the pleasure of having two colleagues originally from Hong Kong, with whom we’ve had some intriguing conversations about their home city.

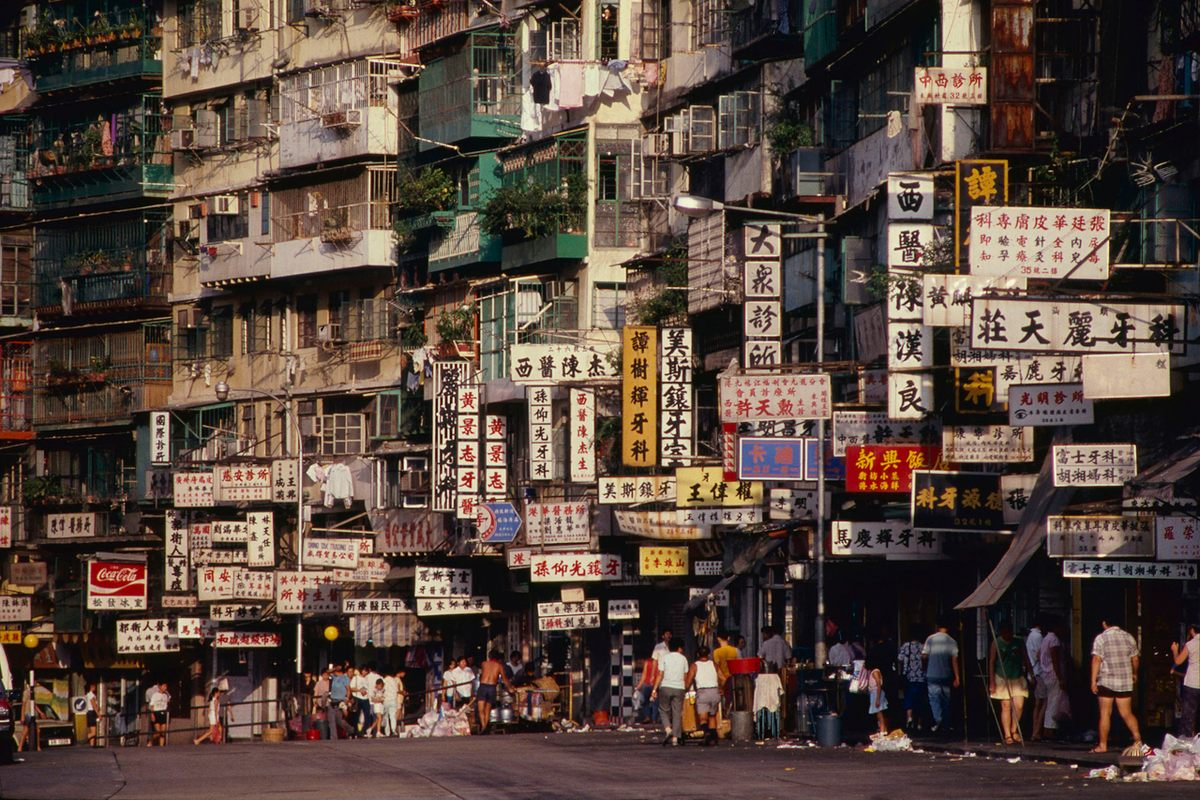

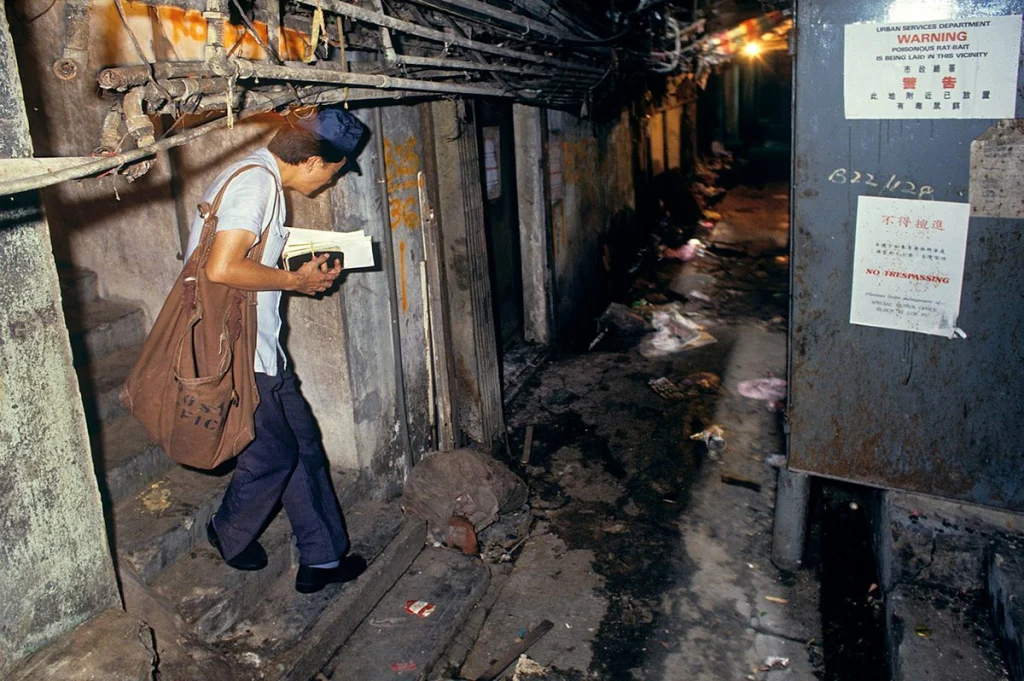

Kowloon was devoid of roads or public spaces, and the only natural light source was the narrow, maze-like passageways that crisscrossed the city. The lack of regulation and oversight led to a patchwork of illegal connections to water and electricity supplies, often resulting in dangerous living conditions. Overhead pipes and wires crossed the alleyways, further adding to the visual chaos.

This ambiguity set the stage for Kowloon’s transformation into a sprawling, unplanned, and unregulated urban labyrinth. It became a haven for refugees, squatters, and criminal enterprises, characterized by narrow, labyrinthine alleyways and a hodgepodge of makeshift structures.

From a personal perspective, it is interesting how every time I see photographs of Kowloon*, they seem to evoke a sense of familiarity, as if I know the place intimately, even when I have never set foot there nor will ever. Similar to the urban environments of other Asian metropolises, population density is high, but all are unique in terms of their historical development, governance, architecture, and culture.

To truly understand the concept of vertical density, we must travel back in time to the early 19th century, when the Walled City began as a military fort. Built by the Chinese government during the Qing Dynasty, this fort served as a defensive stronghold against British colonization. However, when Hong Kong was ceded to the British in 1898, the Walled City fell into a legal limbo, a territory that neither the British nor the Chinese government claimed.

What made Kowloon a prime example of vertical density was its staggering population density. In its heyday, over 30,000 residents called this cramped complex of interconnected buildings home. Stacked high, the area gave rise to an astounding 1.2 million people per square kilometer, making it one of the densest places in the world to ever exist.

Fast forward to modern-day Hong Kong, and the spirit of vertical density lives on, albeit in a more orderly and glamorous fashion. The city boasts one of the most impressive skylines on the planet, the International Commerce Centre (ICC), standing at 484 meters tall, exemplifies the city’s penchant for reaching new heights.

Hong Kong’s vertical density is not just about skyscrapers but also its efficient public transportation systems and compact living spaces. As space becomes more precious, innovative designs such as micro-apartments and vertical gardens, have become integral aspects of Hong Kong’s urban landscape.

Similar to modern-day Hong Kong and in stark contrast to Kowloon, the Walled City, other Asian cities adopt a more organized and strategic approach to urban planning. Though they, too, grapple with the challenges of population density, they tend to employ a more methodical practice of vertical expansion.

For instance, let’s consider the bustling streets of Tokyo. This modern metropolis, like Kowloon, experiences high population density. However, Tokyo sets a great precedent of meticulous urban planning, where towering skyscrapers and an intricate subway system coexist seamlessly. Tokyo’s verticality also encompasses the traditional side of Japan. The historical temples and shrines rise among the more contemporary cityscape, their coexistence gives Tokyo its distinct character.

In Singapore, a city known for its meticulous planning and order, the concept of vertical density has been elevated to an art form. The towering HDB (Housing and Development Board) estates in Singapore are a prime example of high-rise living done right, with meticulous design, modern amenities, and lush green spaces, the complete opposite of Kowloon’s chaotic vertical sprawl.

As we navigate the challenges of land scarcity, burgeoning population densities, and the quest for sustainable urban living, the dichotomy between these two approaches serves as a compelling narrative for place-making and community-making.

In regions where land comes at a premium, the concept of vertical place-making becomes not just an option but a necessity. The lessons from organic vertical density growth, as witnessed in historical examples like Kowloon, teach us that community resilience can thrive even in the most challenging environments. However, in the modern context, safety standards and meticulous planning must be integral to the process.

Safety in urban living is a multifaceted concern, encompassing structural integrity, accessibility, and the overall well-being of residents. The organic growth of vertical density, as seen in historical examples, often lacked formal planning, resulting in a chaotic amalgamation of structures with questionable structural soundness. Learning from this, modern urban planners must emphasize safety standards while embracing the community spirit that organic growth embodies.

Take London, for instance, a city characterised by escalating land prices and a constant surge in population density. Vertical place-making would allow for the efficient utilisation of limited space, without encroaching into the existing green spaces. The challenge lies in striking a balance between the orderly planning that ensures the safety and the adaptable spirit that characterizes organic growth and community development.

Integral to this balance is the incorporation of vertical green spaces and gardens. Vertical gardens not only enhance the aesthetic appeal of high-rise structures but also provide crucial ecological benefits, improving air quality and mitigating the urban heat island effect.

Infrastructure and flexibility for future amenities are also pivotal considerations. Cities are ever-evolving entities, and planning for adaptability ensures that urban spaces can cater to the changing needs and aspirations of their inhabitants.

As we navigate the path toward creating sustainable, vibrant, and safe urban environments for the future, the lessons learned from both organic vertical density growth and meticulous planning are invaluable. The blend of safety and innovation in vertical placemaking is not just a theoretical construct but a practical imperative. It is the blueprint for creating urban spaces that are not only resilient and secure but also dynamic, fostering a sense of community and well-being amidst the vertical expanse of our cities.

*In this article, Kowloon refers to the Walled City, not the current Kowloon.

Leave a comment