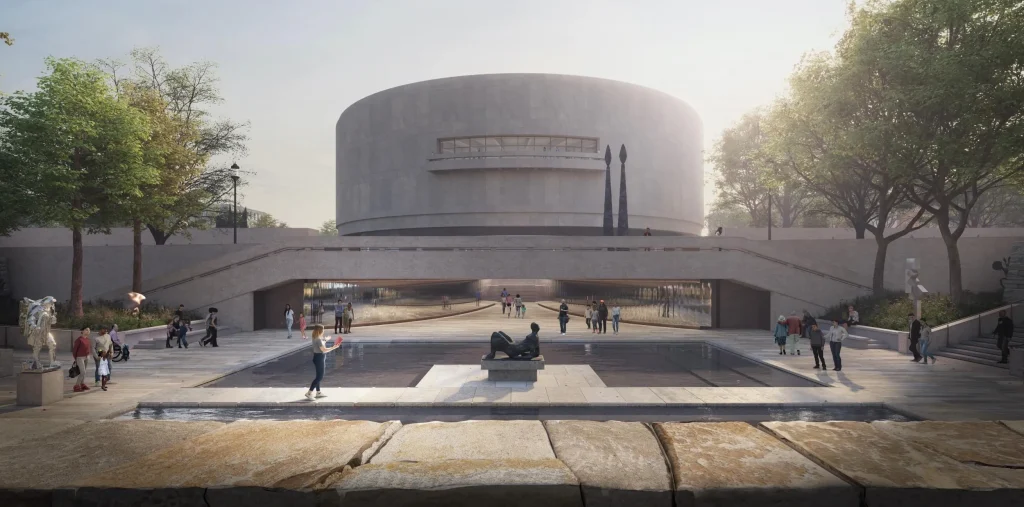

Surrounded by white marble monuments, domed museums, and classical columns, the National Mall in Washington, D.C., is home to a massive concrete ring that appears to hover above the ground: The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

One of the most striking instances of Brutalist architecture in the United States is the Hirshhorn Museum, which was designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and opened in 1974. It is modern art, not only a location to view it. And its avant-garde design still divides, inspires, and defines people almost fifty years later.

A Circular Loop of Art

Consider a solid concrete drum that is 82 feet thick and 231 feet broad. Now raise that drum fourteen feet off the ground while supporting it with four massive legs. Make a circular courtyard that is open to the sky by cutting a hole in the center. Part spacecraft, part fortress, and part architectural sculpture, this is the primary structure of the Hirshhorn.

There’s a reason it was made this way. Bunshaft wants the museum to stick out rather than blend in. The Hirshhorn’s galleries form a circular loop, in contrast to conventional structures that rise vertically or spread horizontally. Without any breaks from corners or hallways, visitors stroll in a leisurely spiral while taking in the artworks.

The building makes no effort to appear graceful or classical. It embraces pure geometry instead, a circle circling a city of rectangles. In this sense, it embodies the very art it was designed to support: audacious, avant-garde, and unafraid to defy convention.

Concrete as a Message

Nearly all of the Hirshhorn is made of concrete, but not the smooth sort found on contemporary sidewalks. Workers literally battered the surface by hand to reveal the rough stone underneath, a technique known as bush-hammering. This method gives the structure a rough, grainy appearance that conveys strength and unadulteratedness.

The museum appeared out of place to many because it was too rough, too odd, and too different from its neighbors. It was even dubbed “the bunker on the Mall” by critics. However, the concrete spoke of honesty to artists and architects. It was not concealed by ornamentation. On its sleeve, it displayed its construction.

Brutalism was a design movement that embraced aggressive forms and raw materials. That mentality permeates every element of the Hirshhorn, from the imposing piers to the slender horizontal windows that elegantly filter light across the artwork.

Sculpture Garden

The Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden is a more subdued, secret realm beneath the museum’s overwhelming bulk. In contrast to the raised museum, the garden is below street level, creating a serene outdoor gallery right in the middle of the city.

The garden, which was created by landscape architect Lester Collins, has open lawns with sculptures of considerable size, terraces, and shallow pools. In a calm environment, away from the masses, visitors can view pieces by artists such as Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, and Rodin.

There is a clear contrast between the building and the landscape. One burrows, the other floats. One is open and green, whereas the other is hefty and substantial. They work together to balance the sculptural vacuum, the concrete bulk, and the manmade and natural space.

Breaking Symmetry

When the Hirshhorn first came out, not everyone was a fan. This round concrete building felt out of place in a city that values tradition and symmetry. But maybe that’s what made it significant.

Hirshhorn was attempting to be relevant to the 1970s, a time when museums were reconsidering how we experience culture, and modern art was pushing the envelope. The Hirshhorn was a novel statement at the time, demonstrating that architecture could be aggressive, abstract, and a component of the art world rather than a neutral backdrop.

The Hirshhorn and other Brutalist structures have gained popularity over time. Something that felt frigid now feels brave. These days, visitors come to experience the structure itself, from the echoes beneath its concrete roof to the dance of sunlight on its rocky façade, rather than just to see what’s inside.

Adapting to Time

The Hirshhorn, like any living institution, has had to change over time. Careful upkeep has been necessary for its concrete façade. The building’s expansion and modification plans, which include the controversial inflatable bubble created by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, have raised questions about how much a Brutalist structure can or should change.

These discussions are a part of a bigger issue that many mid-century structures are currently dealing with: how can we maintain contemporary architecture without erasing it?

Fortunately, this tension has been welcomed by the institution. Within the same circular shell, its shows now feature public performances, digital media, and immersive installations. Once thought to be inflexible, the architecture is turning out to be remarkably adaptable.

The Hirshhorn Museum is a challenge to the surrounding metropolis. It still dares to be substantial and weird in an era when many new museums strive for transparency and tenderness. And in doing so, it serves as a reminder that great architecture is art in and of itself, not just a place to house it.

Leave a comment