Glenstone, a collaborative monument of art, architecture, and environment, is tucked away in the undulating hills of Potomac, Maryland. Charles Gwathmey created a simple limestone gallery when it was first established in 2006 by benefactors Mitchell and Emily Wei Rales.

However, Thomas Phifer and Partners’ ambitious $200 million project in 2018 turned Glenstone into a sculpture environment consisting of eleven concrete-formed Pavilions, encircling a central water court, providing an experience that goes beyond a typical museum visit.

A Journey through Landscape and Architecture

The foundation was established by Gwathmey, but Phifer drastically expanded it to provide a cohesive museum experience. From an object-focused gallery, the focus evolved to an immersive experience of nature, art, and structure.

Visitors first see Glenstone in Arrival Hall, a cozy cedar-clad building with white maple interiors. From there, a route leads them across repaired streams, past a timber bridge, through meadows, and eventually toward Pavilions, which emerges discreetly atop a knoll. The planning of the visitor’s journey, arrive, explore, pause, and then take in the imposing architecture, sets the tone for what is commonly referred to as a slow art experience.

The environment, created by PWP Environment Architecture under the direction of Adam Greenspan and Peter Walker, is an organic ecosystem. More than 8,000 trees, 33 acres of sustainable meadows, reclaimed wetlands and woods, and natural streams all come together to form an organically maintained biodiverse network. The ground slopes in gentle hills formed by the on-site soil, directing water and pedestrians while fusing the natural environment with the constructed environment.

Glenstone Pavilions

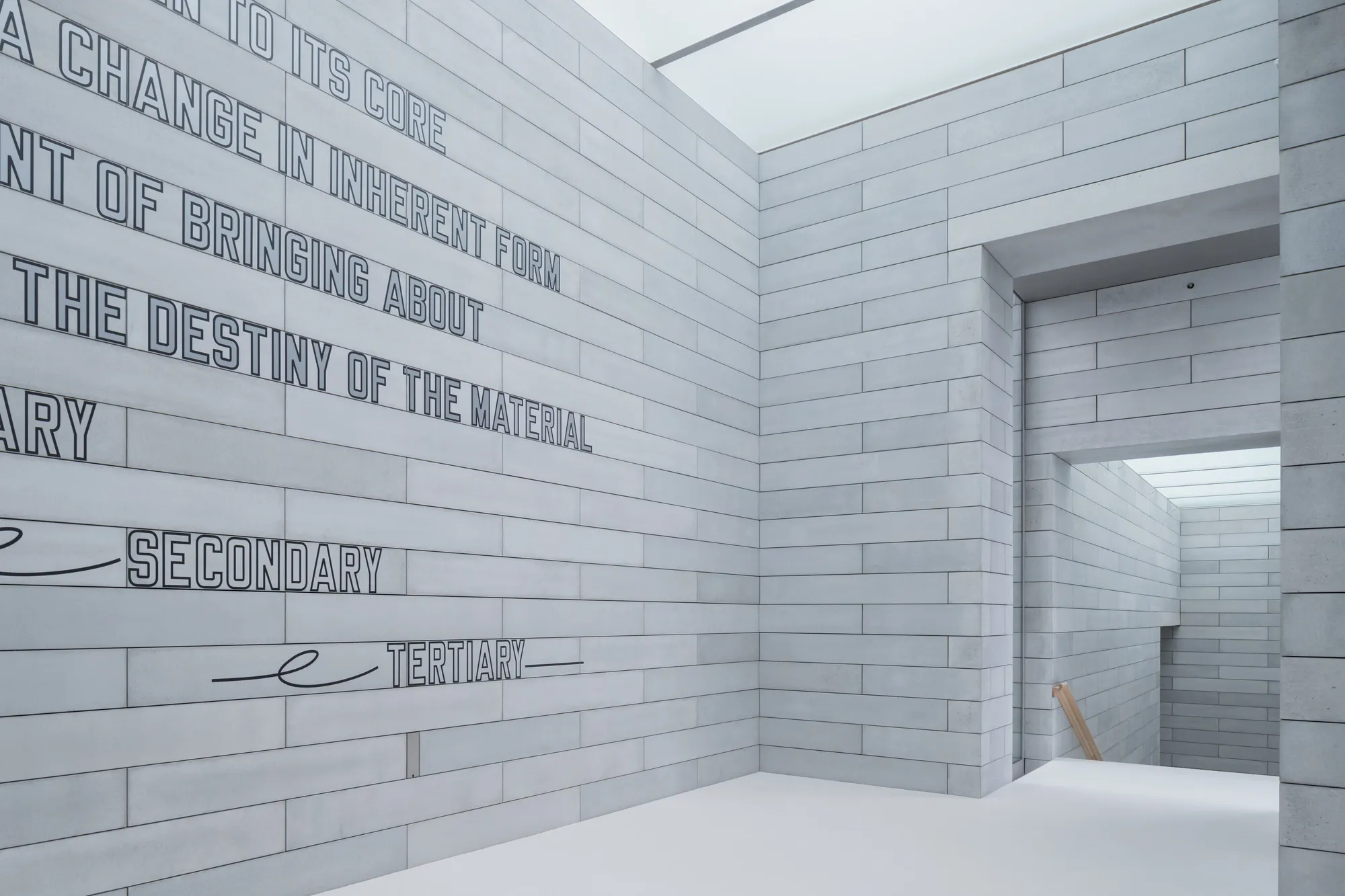

About 26,000 board-formed precast concrete blocks, each measuring 1.8 m by 0.3 m, make up Phifer’s Pavilions. These blocks are arranged to imitate masonry in Japanese style temple walls, such as Kyoto’s Ryōan-ji.

Seasonal color fluctuations give façades a sense of quality, ranging from pale in summer to dark gray in cool times. Phifer purposefully chose to represent monumentality and slow time by making buildings seem massive and permanent.

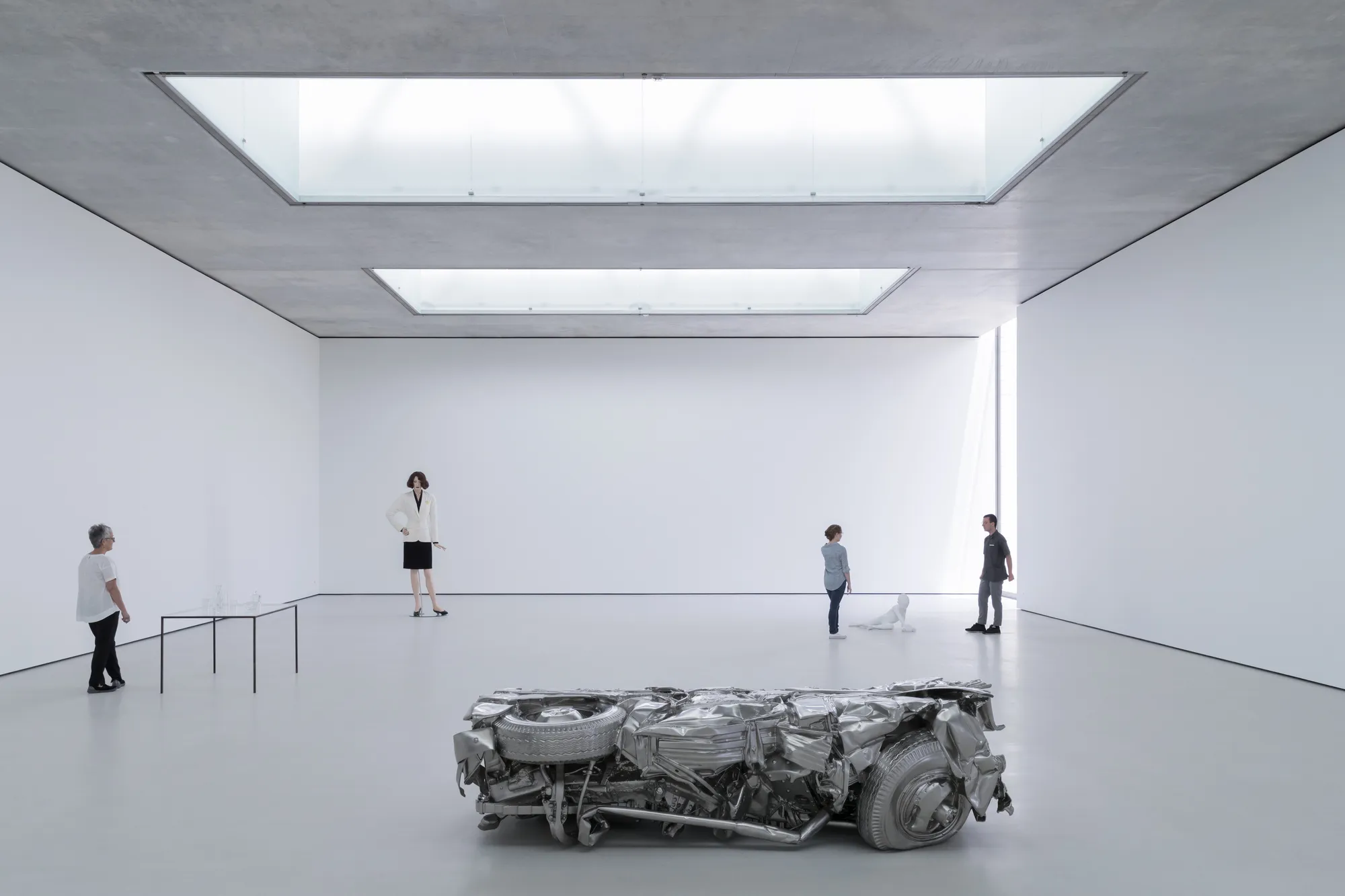

Even though Pavilions are sturdy, they are broken up by enormous glass walls that frame the inner Water Court and the surrounding landscape. These walls are made of insulated panels and can reach a height of thirty feet.

These walls provide visitors with uninterrupted vistas since they are supported off the edge of the slab by hidden stainless-steel mullions that also serve as guardrails for roof terraces. The interior/exterior boundary is eliminated by the glass volumes created by thin moment connections and hidden structure.

Light as Architectural Element

Phifer uses daylight to heighten his spatial storytelling. Each gallery has full skylights, oculi, laylights, or clerestories depending on the artwork. Large canvases by Brice Marden or triptychs by On Kawara are examples of rotating artwork that is placed in volumes that are proportioned to improve scale and mood. In one pavilion, the sky lies immediately above a Heizer earthwork, framed by a space without a roof, making the passage of the sky more tactile.

Natural light is purposeful, not just practical. Phifer choreographs sunlight across time by placing rooms in accordance with the cardinal directions. Light is softly diffused by clerestories and frosted windows, while above monitors provide adjustable lighting without detracting from the artwork. Changing shadows and seasonal colors inform the experience of galleries, passageways, and the water court, promoting mindful awareness of the world outside of art.

Technological Arrangements

Humidification and mechanical equipment are hidden above daylights or beneath galleries; radiant cooling reduces the chance of condensation around large glass surfaces. In order to preserve the aesthetic integrity of minimum surfaces, fire sprinklers, sensors, and AV conduits are discreetly inserted into concrete joints. In order to accommodate rotating exhibitions without interfering with environmental control systems, gallery walls are equipped with concealed equipment.

Crucially, the architectural layout also facilitates more in-depth discussions about the environment. The Environmental Center offers information on water conservation, low-impact upkeep, composting, and organic landscaping, demonstrating Glenstone’s commitment to cultural care that goes beyond art.

A Sanctuary of Slow Contemplation

Glenstone’s fusion of architecture, art, and landscape has been commended by critics, including Philip Kennicott of the Washington Post, The Architectural Record, and AIA juries. Gordon Iovine referred to it as one of the best architectural creations of 2018. Its illuminated thresholds were compared to Zen sanctuaries and Italian hill towns in the journal Azure.

Emily Rales envisioned slow art, where visitors’ breath would synchronize with soft architectural rhythms, their senses would awaken, and their pulses would slow. In order to provide space for interaction, Glenstone purposefully keeps a daily footfall of 400–600 people.

Glenstone is a living statement of architectural philosophy, much more than a museum of art. Thomas Phifer and Partners created a number of concrete volumes that breathe with light and landscape, drawing inspiration from postmodern urbanism and Zen gardens.

Above all, the museum encourages visitors to slow down, observe the interaction of material and daylight, and re-establish a connection between art and nature. It also incorporates systems knowledge into its walls and emphasizes environmental advocacy through its gardens.

In a time when speeding is the norm, Glenstone provides silence. Its architectural brilliance subtly combines movement, space, light, and environment to create a haven where people can rediscover the power of being present.

Leave a comment