An ancient city that was carved and not constructed rises from the cliffs in the parched mountains of southern Jordan. The capital of the Nabataean kingdom, Petra, is more than just one of the Seven Wonders of the World or a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It is a powerful architectural statement that questions how we think about permanence and building. Its fundamental premise is that architecture can be unearthed from the ground. Petra’s rock-cut design is a stylistic decision and a sophisticated architectural approach with roots in geography and culture.

What is Subtractive Architecture?

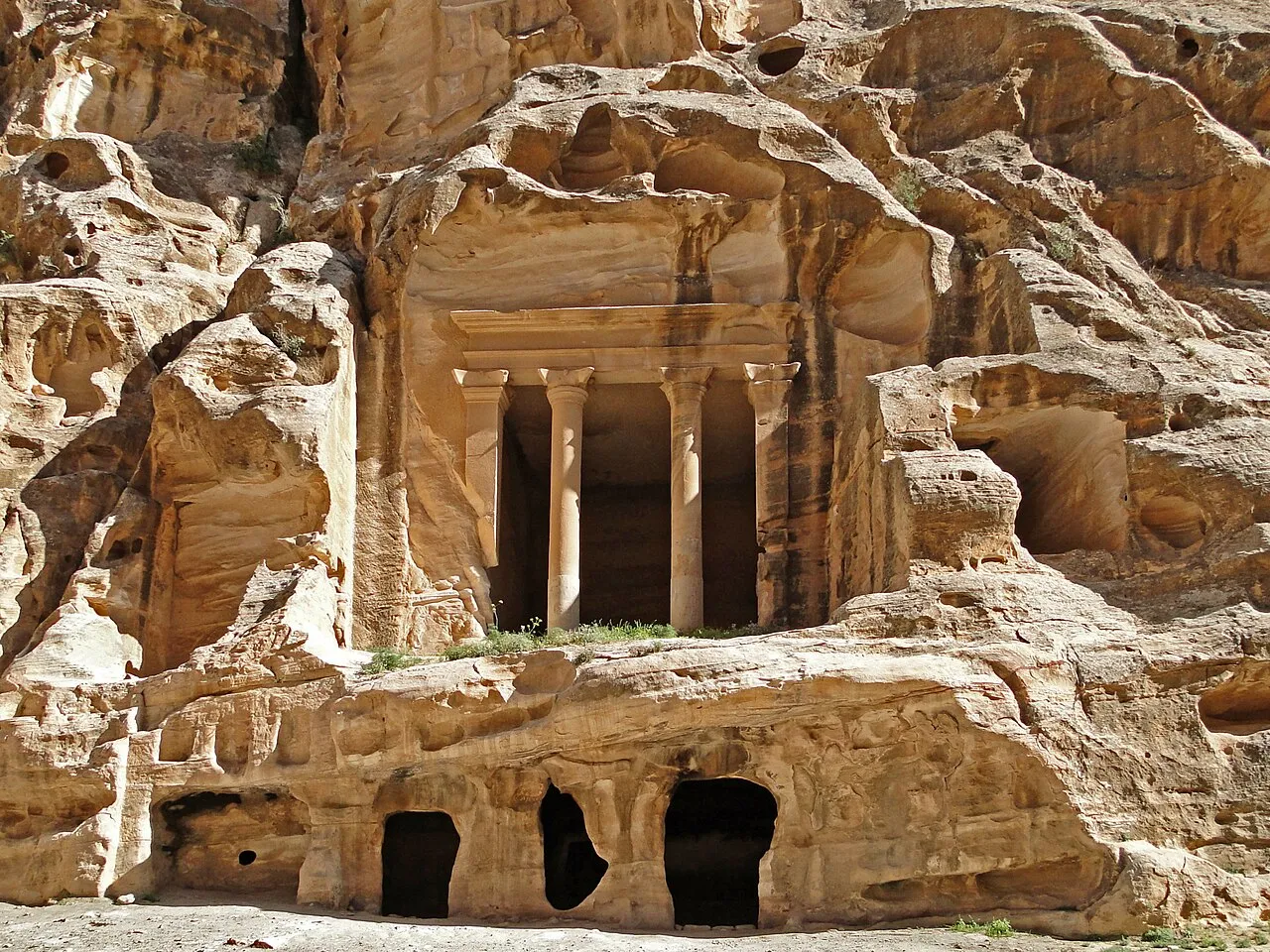

As opposed to traditional construction, Petra is the outcome of subtraction. It uses an additive method to assemble materials like stone blocks, bricks, and lumber. Monumental facades, tombs, shrines, and even staircases were fashioned from live rock by the Nabataeans, who cut their city into rose-colored sandstone cliffs.

This subtractive method necessitated a radically different approach to design. With limited tolerance for structural mistakes, builders had to envision the entire construction from the beginning, starting at the top and working their way down.

In addition to demonstrating exceptional workmanship, this approach displays a deep conversation between building and landscape. Architecture in Petra is a product of the landscape. The natural strata of the rock surface frequently affect the rhythm and design of the façade, and the shapes of sandstone cliffs become compositional components.

Sustainability and Climatic Intelligence

In addition to being a sculpture, Petra’s rock-cut building served as a climate remedy. The interiors are protected from the intense desert heat outside by the natural insulating effect of the sandstone cliffs’ thermal mass. The stone maintains its coolness throughout the day and releases its stored heat at night, which is a passive thermal comfort technique.

Centuries before such issues were widely recognized, the Nabataeans successfully decreased the need for extra materials and produced environmentally friendly designs by burying buildings in the ground. As architects and planners deal with the issues of sustainability, carbon footprint, and climate resilience, these passive design strategies are becoming more and more relevant.

Symbols and Expressions

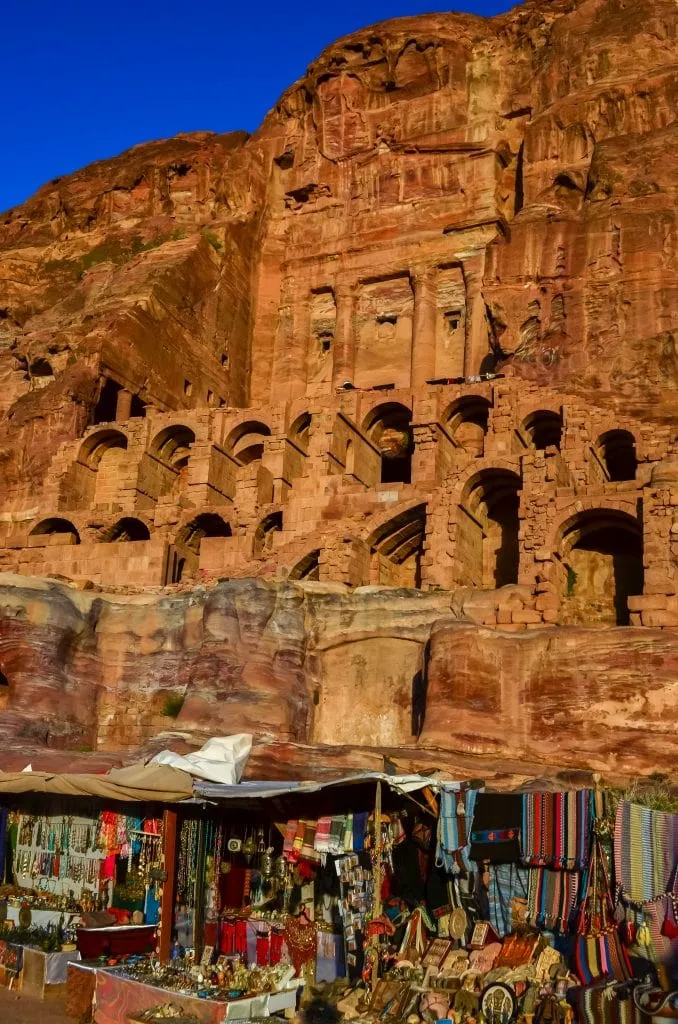

Al-Khazneh (The Treasury), Petra’s most famous building, is a prime example of the city’s weaving of regional style with international design. Its intricate façade is completely carved into the rock face and includes triangular pediments, sculpted niches, funerary iconography, and Hellenistic Corinthian columns. Its ability to resemble a freestanding temple and give the appearance of bulk and void on a vertical surface is its expertise.

Petra’s façades mimic architectural orders from Egypt, Greece, and Rome, continuing this visual language. However, without any structural purpose, these borrowed forms are recast in stone. The pediments crown no roof, and the columns bear no weight.

They are sculpted manifestations of cosmopolitanism and prestige. The Nabataeans assimilated and modified architectural themes to create a regional style appropriate for their own geological setting rather than replicating them.

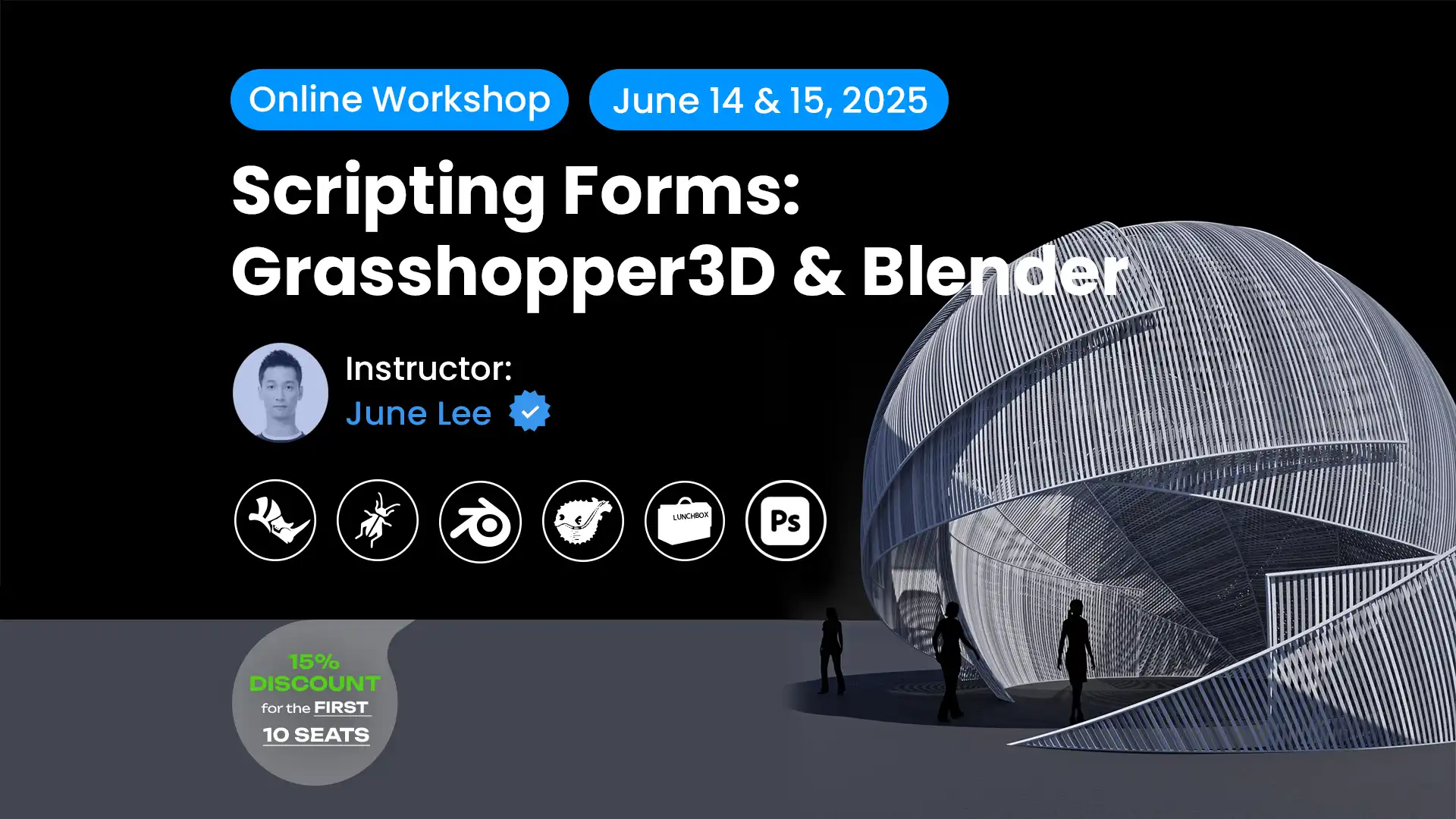

Petra’s architecture was calculated, contextual, and deeply responsive to its environment. Today, architects are rediscovering these values through computational design and simulation. Explore how form, climate, and culture intersect in our advanced architecture workshops at PAACADEMY.

Urban Infrastructure

Beyond its aesthetic appeal, Petra’s rock-cut design is a mix of infrastructure with civic processes. Temples, marketplaces, and bathhouses, many of which were partially excavated into the surrounding rock, were arranged along a main colonnaded thoroughfare in the city. The built environment expanded into the landscape as a network of connected and sculpted areas.

The water infrastructure is arguably the most amazing. In order to collect and distribute rainwater in the severe desert climate, the Nabataeans built reservoirs, dams, and secret aqueducts carved into rock faces.

Tens of thousands of people were supported by this system, which also made it possible for gardens, fountains, and covered courtyards to flourish in the middle of the dry plateau. Once more, rock-cutting had both spatial and practical uses; it was architecture and infrastructure combined into one.

Monumentality

Petra’s monumentality is among its most intriguing architectural paradoxes. The tombs and temples are incredibly large; their façades, which are carved as though from giants’ imaginations, reach heights of 30 to 45 meters. However, these constructions lack volumetric mass in spite of their grandeur. The façade is supported by the cliff itself rather than any structural framework. The buildings’ monumentality stems from what was taken down, not from what was built.

The concept of permanence portrays this reversal of architectural norm, which involves creating depth out of solidity rather than building height from the ground up. It is impossible to move or disassemble Petra’s structures. They are exclusive to the location where they were carved. Petra reminds us of an architecture that is immovable and inextricably linked to the soil in a time when prefabrication and mobility are the rage.

Legacy and Influence of Petra

Together with the rock-hewn chapels of Lalibela in Ethiopia and the cave temples of Ajanta and Ellora in India, Petra is one of the best examples of rock-cut architecture in the world. Its architectural significance, however, comes from the issues it poses for modern design practice.

What if the topography served as a design collaborator rather than only a limitation? What if location and permanency were more important than scale and speed? What if our structures could weather gracefully over time, becoming part of the landscape instead of existing outside of it?

Petra provides architects of today with a significant case study in minimal material intervention and contextual design. Its teachings apply to both urban interventions in crowded, ancient cities and distant eco-resorts. It challenges us to envision architecture differently.

Petra is a stone city with intentional architecture. Structural logic, environmental intelligence, and cultural hybridity are embodied in its rock-cut design. Petra reminds us that often the most audacious thing to do is to dig deeper than higher.

Leave a comment