Why Is Samarkand a Key City on the Silk Road?

Centuries of trade and conquest have transformed Samarkand, one of the oldest inhabited towns in Central Asia, into a historic urban masterpiece. The city was a cultural melting pot for people from China, Persia, India, and the Mediterranean, and was once a key stop on the Silk Road. It is a case study of how physical form reflects civilizational aspiration because of its unique architecture, imposing public spaces, and resilient urban design.

Samarkand is a real example of how towns can use design to represent social, scientific, and spiritual development, from the recognizable blue domes of Timurid mosques to sophisticated madrasas and antiquated irrigation systems.

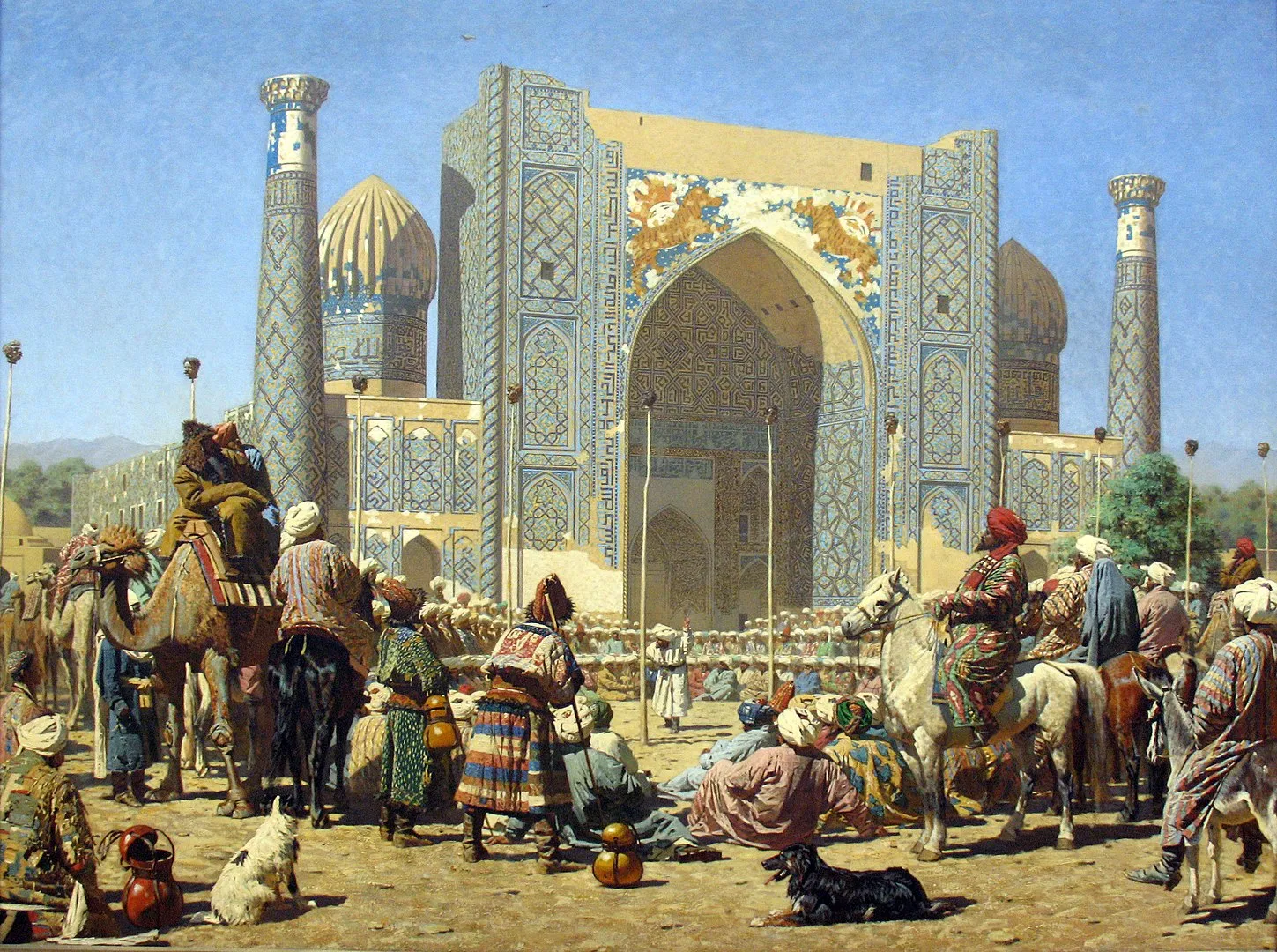

Jewel of the Silk Road

Samarkand flourished as a Silk Road city, where camel caravans and merchant ships linked far-flung empires, thanks to its advantageous location in the lush Zeravshan River valley. Due to this function, the city became a dense urban organism with cosmopolitan neighborhoods, artisan quarters, religious sites, and commerce lines.

With subterranean qanat systems providing clean water to residences, gardens, and mosques, the early city was influenced by sustainable water planning. The city’s natural street plan mirrored its role as a crossroads for caravans, adaptable, versatile, and adhering to the surrounding terrain. Samarkand achieved a human-scale urbanism that still influences modern sustainable planning.

Timurid Architecture

Timur (Tamerlane) turned Samarkand into the cultural and architectural center of his kingdom in the fourteenth century, ushering in the city’s golden age. Timur had an ambitious plan: to build a new type of capital that projected political power through art and architecture, outshining cities like Isfahan and Baghdad.

Timur brought in architects and craftsmen from all around the empire, resulting in Turkic, Mongol, and Persian architectural styles. As a result, Timurid architecture, characterized by enormous domes, intricate tile mosaics, and exact geometric order, was born.

The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, a huge, axially oriented religious structure featuring a gigantic entry iwan, turquoise-glazed domes, and calligraphic inscriptions, is one of the period’s crown jewels. It demonstrated how monumentality could coexist with precise detailing and mathematics. It was constructed to please natives and visiting dignitaries.

The Registan: Public Space as Civic Symbol

The Registan, a ceremonial square surrounded by three imposing madrasas, is an essential component of any discussion of Samarkand’s architecture. Sher-Dor (1619–1636), Tilya-Kori (1646–1660), and Ulugh Beg (1417–1420) each symbolize a distinct stage of Samarkand’s architectural development.

The Registan is a remarkable example of how culture and urban planning were integrated into a single public area. The square served as a civic and intellectual hub because these madrasas included lecture halls, libraries, and dorms in addition to being sites of religious instruction. With its symmetrical façades, lavishly tiled surfaces, and natural pedestrian movement, the Registan’s spatial choreography exemplifies classic public space design ideas that planners still find useful today.

Ulugh Beg’s Legacy

Ulugh Beg, an astronomer and mathematician, transformed Samarkand into a scientific hub in the early 15th century by establishing a famous observatory. Ulugh Beg was Timur’s grandson, and he constructed for knowledge, not power.

An enormous sextant, partially buried underground, was kept at the Ulugh Beg Observatory and enabled exceptionally precise astronomical computations. It was a unique example of scientific architecture in the Islamic world, with a logical, minimalistic, and informed design. It demonstrates how civic aspirations and intellectual depth may still be expressed through function-driven design.

Soviet Influence and Urban Transformation

Samarkand had a significant urban development during the 19th and 20th centuries while under Russian and then Soviet control. Parts of the city were covered with a new colonial grid that included Soviet-style houses, wide boulevards, and administrative buildings. Although modernization provided conveniences, it frequently came at the expense of traditional neighborhood structures (mahallas) and vernacular architecture.

Many of Samarkand’s historic sites have survived in spite of this. Although several of the city’s major monuments were over-restored or lost their original materiality, restoration efforts throughout the Soviet era stabilized them. These disparate urban strata now cohabit, providing a singular glimpse of Central Asian urban development.

Revival and Urban Preservation

Since 1991, when Uzbekistan gained its independence, Samarkand has been restoring its architecture and culture. The city has benefited from national and international preservation funding since it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001.

Carefully planned renovations have been made to important monuments including the Bibi-Khanym Mosque and the Shah-i-Zinda necropolis. More significantly, contextual urban planning that promotes historical tourism is currently being given top priority by local governments and international partners.

Traditional neighborhoods are being protected from overdevelopment, water-efficient landscaping is being reintegrated, and local construction crafts like brick masonry and glazed tilework are being revived.

What Can Modern Architects and Planners Learn from Samarkand’s Urban Design?

Samarkand offers unique insights for today’s architects, urban planners, and legislators. The way its architecture has changed over time demonstrates the strength of cultural layering; new additions were built without destroying the old, creating a robust and rich urban fabric.

A prime example of how architectural form may project soft power is the Registan, a monumental piece of public architecture intended to impress foreign traders and diplomats in addition to locals.

The intricate water management systems of Samarkand, such as qanats and lush garden designs, highlight how water-centric urban planning can support life in desert areas, a lesson that is becoming pertinent in the age of climate change.

Furthermore, the city’s hybrid architectural typologies, where observatories, madrasas, and caravanserais served as civic, commercial, and educational venues all at once, offer a convincing example for modern mixed-use projects that aim for both density and diversity.

If the layered history and thoughtful planning of Samarkand spark your curiosity, there are new ways today to explore how design, technology, and culture can come together. At PAACADEMY, we offer learning experiences that build on these timeless ideas, introducing contemporary workflows and computational design tools that help architects rethink urbanism for the challenges of today and tomorrow.

A Living City

Samarkand is a functioning urban system rather than just a historic Silk Road city that has been preserved over time. Its soul is in its changing relationship with memory, community, and craft, even though its skyline is characterized by towering domes and sparkling minarets.

Samarkand serves as evidence that cultural continuity and contemporary advancement may coexist in a time when fast urbanization sacrifices history for speed. Samarkand provides an architectural compass as communities everywhere work toward sustainable, identity-driven growth, one that not only points to the past but also toward a future where humankind and history can coexist.

Leave a comment