For many years, architecture has been about form, function, and flow. Designers have changed the way we live, work, and move through space. They decide how light comes into a room, how people move around a floor plan, and how buildings fit in with their surroundings. But there’s a developing aspect that’s harder to perceive but more and more important: how buildings think.

Smart buildings are no longer ideas from the future. They are here, and they are changing quickly. There is more to the glass facades and sculptural structures than meets the eye. There are operating systems that collect data, make judgments, and subtly change how spaces behave. Building management systems (BMS) generally take care of this hidden layer, which is becoming the brain of architecture. For architects, knowing how these systems work is not just beneficial; it’s necessary.

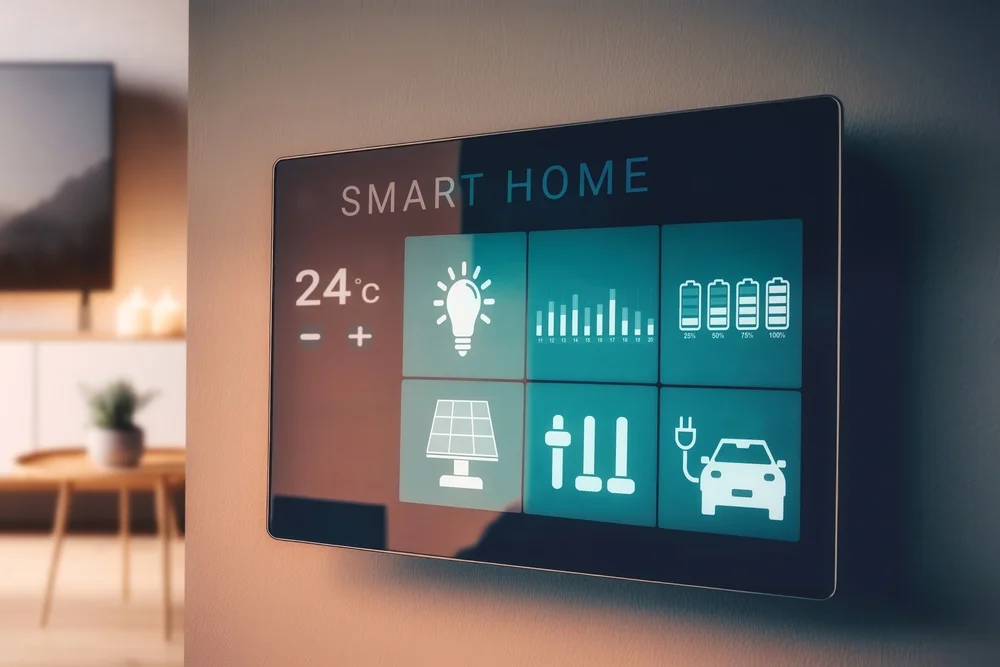

More Than Control Panels: What Operating Systems Actually Do

If you thought that a wall-mounted thermostat or lighting control panel was the most intelligent thing about a building, you should think again. There are a lot of sensors, data nodes, and algorithms hidden in modern smart buildings. These do more than just control how much energy is used; they also change how it feels to be in a location.

Smart operating systems govern everything from the temperature and ventilation to the lighting, based on how many people are in the room, the automated blinds, and even the maintenance schedule. They can make things more pleasant right away, estimate when the system will break down, and adjust how well it works based on the time of day or the weather.

Still fuzzy on how it works? Here’s the concept of BMS explained: A BMS gets information from all across a building, like sensors on HVAC units, lighting grids, doors, and water systems. It then interprets that information and sends commands to change how things work. It’s like a conductor leading an orchestra of mechanical and digital parts that learn, change, and get better over time.

Why This Matters for Architects

Architects don’t usually have to install BMS platforms or write automation sequences, but the choices they make about design can either make these systems work better or worse.

The way mechanical rooms are set up, the choice of facade systems, or the arrangement of natural ventilation channels can all affect how well a smart system works. Daylight-responsive lighting won’t be very effective in a layout that doesn’t account for solar orientation. And HVAC optimization may struggle in zones with unpredictable or poorly planned occupancy.

In short, the building’s brains and bones need to align. Architects who understand how smart systems function can design with them, not just around them, resulting in buildings that perform better, feel better, and cost less to operate over time.

Buildings as Responsive Systems

Think of a building less as a static container and more as a living system. In a smart building, actions have ripple effects. Open a window, and the HVAC might scale back. Enter a room, and the lighting shifts automatically. Too many people in a conference area? Airflow increases before it gets stuffy.

This is where architecture begins to dance with data. The space reacts to the people inside it. The interior environment adapts not just once, but throughout the day. And the more integrated the system, the more refined that response becomes.

The opportunity here isn’t just about efficiency, it’s about designing spaces that anticipate needs. This can lead to more intuitive environments where occupants feel a building is responding to them, even if they don’t know why.

Rethinking Architectural Intent Through Data

Historically, architects have relied on intuition, precedent, and programmatic needs to define design. But data is now emerging as a new design partner. Smart operating systems log how people use spaces: where they gather, which rooms stay empty, and how systems perform under different loads.

This feedback loop can inform future projects or even influence live adjustments in the current one. Architects can collaborate with operations teams post-occupancy to evaluate how the building really works versus how it was expected to.

Imagine designing a learning center and, a few months after opening, reviewing heat maps showing foot traffic, room usage, and comfort complaints. These aren’t critiques, they’re opportunities. They reveal how the built environment performs under real-world conditions and offer a richer basis for improving design.

The Aesthetic Impact of Intelligence

Some architects may worry that smart systems will compromise design purity or visual control. But intelligence doesn’t need to be visible. In fact, many of the most successful smart features are quietly integrated: hidden sensors, flush-mounted actuators, discreet control panels.

What matters is that design and systems speak the same language. When an HVAC system adjusts based on radiant heat coming through a glass wall, that wall’s performance and purpose come into sharper focus. When blinds lower automatically in a double-height lobby, the interplay of light, shade, and experience becomes something dynamic.

Smart systems don’t dilute design; they offer new tools to shape it.

Designing for Flexibility and Lifespan

Buildings age. Uses change. Tenants move. But smart platforms can help buildings adapt rather than decay.

A well-integrated BMS lets you upgrade, re-zone, and repurpose spaces from a distance without having to do any expensive rewiring or building. Lighting grids can be reprogrammed for new layouts. Ventilation schedules can change with occupancy. Energy goals can be recalibrated in response to real-time data.

Architects who design with flexibility in mind, from raised floors to modular ceiling systems, enable smart technologies to evolve alongside the building. This isn’t just future-proofing, it’s design with a longer attention span.

Challenges Architects Should Know About

Of course, it’s not all seamless. Smart systems come with their own challenges, and architects should be aware of them:

- Integration limits: Not all systems talk to each other easily. Coordination during design development is key.

- Sensor placement: Poor positioning can render features useless (e.g., motion sensors behind doors).

- Cybersecurity: With more connectivity comes more vulnerability. Systems need to be safe and up-to-date on a frequent basis.

- User interface: The smartest system means nothing if building occupants can’t use it intuitively.

These are solvable problems, but they require collaboration between architects, engineers, system integrators, and IT consultants, ideally starting early in the design process.

Shifting Roles: Architects as Systems Thinkers

As buildings get smarter, the architect’s role expands. Beyond drawing floor plans and facades, architects are now part of a larger conversation about data, responsiveness, and user experience.

It’s not about turning designers into programmers. It’s about becoming informed collaborators, understanding what’s possible, asking better questions, and designing spaces that support intelligent behavior.

This shift mirrors the evolution of other fields. Just as industrial designers now consider UI/UX in physical products, architects must now consider how a building feels when it interacts with people.

Conclusion: Designing for Awareness, Not Automation

Smart building operating systems aren’t just about automation. They’re about awareness. Knowing who is in a space, how it is being utilized, and what it needs to work better. This means that architects will have to think about a new layer of design that is less visible but just as important as structure or light.

Buildings are no longer just backgrounds. They respond, record, and adapt. And the more thoughtfully they’re designed, the more gracefully they do all three.

To explore more on this evolving intersection of architecture and building intelligence, and to find useful insights on smart building, architects and designers can begin engaging with the systems shaping the next generation of built environments.

Leave a comment