The Serpentine Pavilion in London becomes one of the most anticipated architecture events on the global design calendar. This year’s 2025 commission marks a particularly playful turn. Designed by legendary British architect Sir Peter Cook in collaboration with The LEGO Group, the “Play Pavilion” transforms Kensington Gardens into a lively, colorful, and curious space that invites us to reimagine the relationship between architecture, imagination, and childhood.

At first glance, the Play Pavilion looks like something lifted from a child’s daydream. With its bold primary colors, textured surfaces, curving forms, and toy-like detailing, the structure doesn’t resemble a conventional building. It feels more like a living sculpture, a whimsical construction made from a child’s imagination and an architect’s vision. But beneath the lighthearted exterior lies a thoughtful exploration of serious architectural ideas.

A Pavilion Rooted in Joy

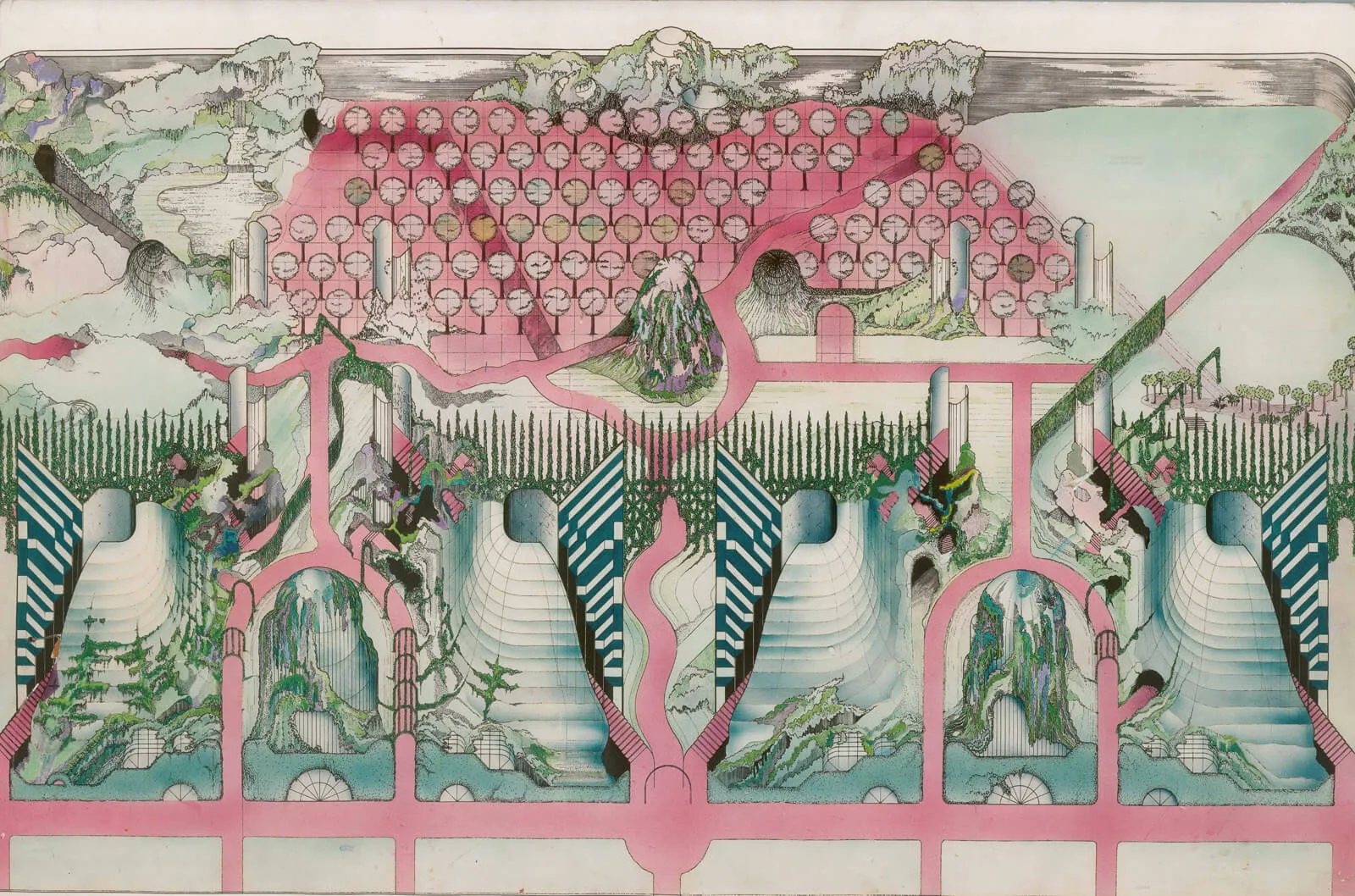

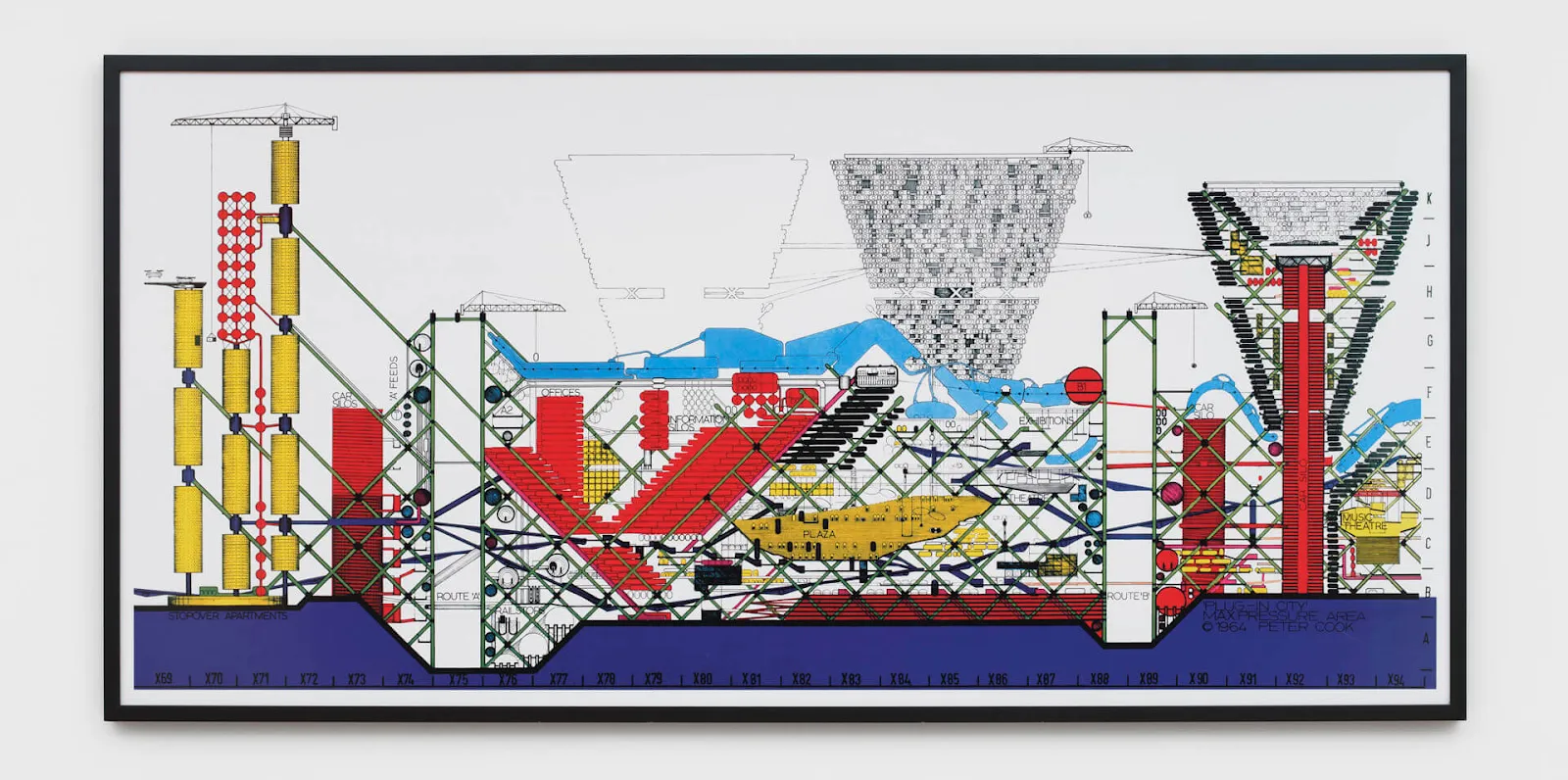

Peter Cook, now in his late eighties, is no stranger to architectural experimentation. As a founding member of the avant-garde Archigram collective in the 1960s, he has spent much of his career challenging norms and rethinking how buildings should look and behave. His design for the 2025 Serpentine Pavilion is no exception. It embodies many of the ideals Archigram stood for: mobility, playfulness, modularity, and accessibility.

The idea of “play” is central here as a design strategy. In partnership with the LEGO Group, Cook has created a space that invites physical and imaginative engagement. The Pavilion is for looking at, it’s for moving through, sitting inside, and being part of. This approach aligns with the broader goals of the Serpentine’s summer program, which often aims to open up architectural discourse to wider audiences.

Inspired by LEGO, Built for the Senses

While the Pavilion is not made of LEGO bricks, the influence is unmistakable. Its bright palette of vivid reds, yellows, blues, and greens mirrors the iconic color system of LEGO sets. The building blocks of the structure, both metaphorically and materially, evoke the modularity and assembly logic of LEGO play.

Curved walls ripple and bulge, giving the Pavilion a sense of movement and flow. Organic forms replace the rigid geometries of many modernist structures. Some surfaces are scaled or textured in ways that recall giant toy bricks, while other parts are smooth and inviting to touch. Openings are cut at unexpected angles, guiding light in playful ways and inviting visitors to peek through, climb, or duck under.

This design philosophy reflects what Cook calls “formative play,” a process of discovering through doing and learning through interaction. Cook described the Pavilion as a “theatre of formative play,” where architecture becomes a stage for unstructured creativity.

Architecture as an Experience

The Play Pavilion is a collection of interconnected zones. Each part offers a slightly different atmosphere, some sheltered and calm, others open and airy. Visitors move freely between these areas, encountering unexpected corners, framed views of the park, and shaded nooks for rest or conversation.

This spatial variety serves both aesthetic and practical purposes. On one level, it encourages exploration. On another, it accommodates a wide range of activities, from performances and workshops to simple lounging. The Pavilion is fully open to the public and entirely free to access, underscoring its mission as a democratic and inclusive architectural work.

The interior spaces are designed with tactility and scale in mind, inviting people of all ages. Children may see a fantasy playground, while adults might be reminded of childhood wonder. That dual-layered reading is part of what makes the structure so rich that it rewards both a playful and a reflective experience.

In many ways, this Pavilion feels like a full-circle moment for Peter Cook. His early work imagined inflatable cities, plug-in modules, and mobile landscapes long before digital modeling made such ideas mainstream. The Play Pavilion feels like a real-world realization of those once-speculative dreams.

It’s also significant that this is his first solo architectural project in London. After decades of shaping the discipline from the edges, Cook is now celebrated as an elder statesman of visionary design. His collaboration with LEGO, a company equally known for inspiring imagination, makes perfect sense. Both believe in the idea that building should be joyful, social, and open-ended.

Since its opening in June 2025, the Play Pavilion has drawn wide attention from critics, designers, and the public alike. The project for bringing “the spirit of childhood into the realm of high architecture.”

In an era where design often serves commerce or prestige, the Play Pavilion’s sincerity and sense of delight feel almost radical. Peter Cook’s Lego Serpentine Pavilion is a reminder that architecture can be soft, silly, experimental, and still deeply intelligent.

Leave a comment