Prior to the emergence of the glass skyscraper and the machine age, architecture was the most durable means by which societies conveyed their values and worldviews. Pre-modern architecture embodied visual narrative and cultural symbolism long before “modernism” reduced buildings to their most basic functions.

Each architectural movement, from the pyramids of ancient Egypt to the Renaissance’s domed cathedrals and the Baroque’s theatrical excesses, contributed to the form and space that still shapes architecture today. The development of important pre-modern styles is traced below, shedding light on how they influenced cities and human thought across millennia.

The Beginning of Pre-Modern Architecture: Egypt, Greece, and Rome

All subsequent design was built upon the architectural heritage of earlier societies. Architecture in ancient Egypt (c. 3000–30 BCE) was closely linked to both cosmology and governmental power. The Egyptian preoccupation with order, eternity, and monumentality is best illustrated by the colossal pyramids of Giza. An architectural language of permanence and heavenly alignment was expressed in these enormous stone constructions that were oriented in relation to celestial bodies. Massive columns, axial symmetry, and intricate sculptures that told religious stories were characteristics of temples like Karnak and Luxor.

In contrast, humanism, proportion, and civic life were the main tenets of Ancient Greek architecture (c. 900–100 BCE). Temples like the Parthenon of Athens were constructed as celebrations of human intelligence. The classical orders, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, were brought by the Greeks and developed into typologies of embellishment and proportion. Their architecture foreshadowed the principles of the Renaissance more than a thousand years later by emphasizing harmony and logical beauty.

Greek design was amplified and inherited by the Romans (c. 500 BCE–476 CE), who used engineering to change buildings. Structures like the Pantheon and aqueducts were able to span enormous areas due to their arches, vaults, and concrete construction. Roman baths and the Colosseum place a strong focus on social utility and public infrastructure. Roman pragmatism and spatial control were also evident in urban planning, which included grid systems and forums.

Romanesque and Byzantine

Sacred architecture replaced civil architecture with the fall of the Roman Empire. Located in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), the Byzantine style (c. 330–1453) combined Christian theology and Roman engineering. With its enormous dome dangling over a square base, the Hagia Sophia employed pendentives to give the impression that it was hovering in space, architecture that served as a haven and a window into heaven. Classical sculpture was superseded by mosaics and elaborate iconography, which put symbolic meaning ahead of realism.

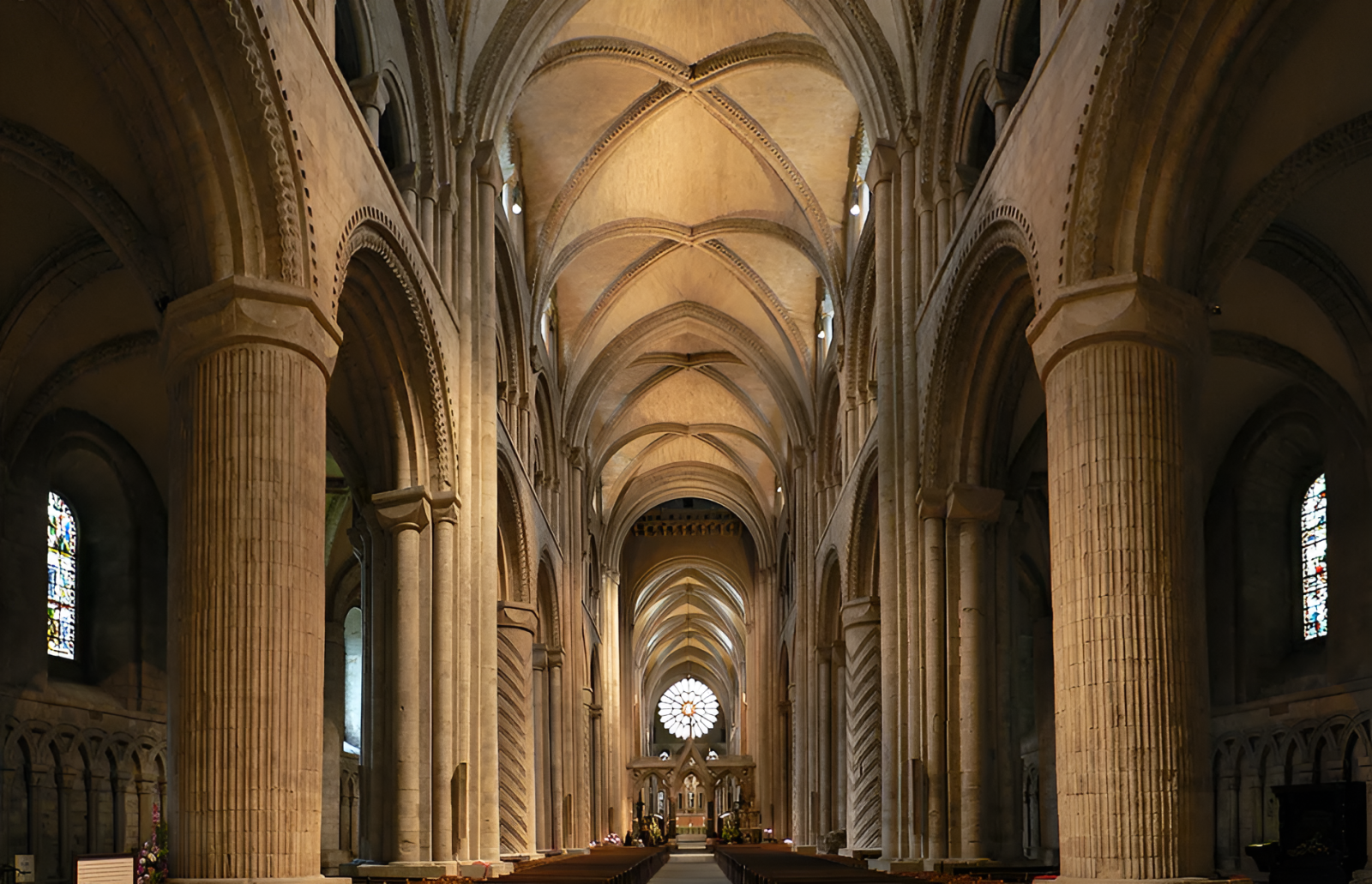

Romanesque architecture (c. 1000–1150 CE) emerged in the early medieval era and was characterized by barrel vaults, rounded arches, and hefty stone walls. Romanesque cathedrals, such as the Abbey of Cluny, were fortress-like, stressing protection and spiritual seriousness. They were inspired by monastic ideals and Roman predecessors. These structures frequently functioned as pilgrimage destinations, bridging geography and religion with durable stone.

The Gothic Revolution

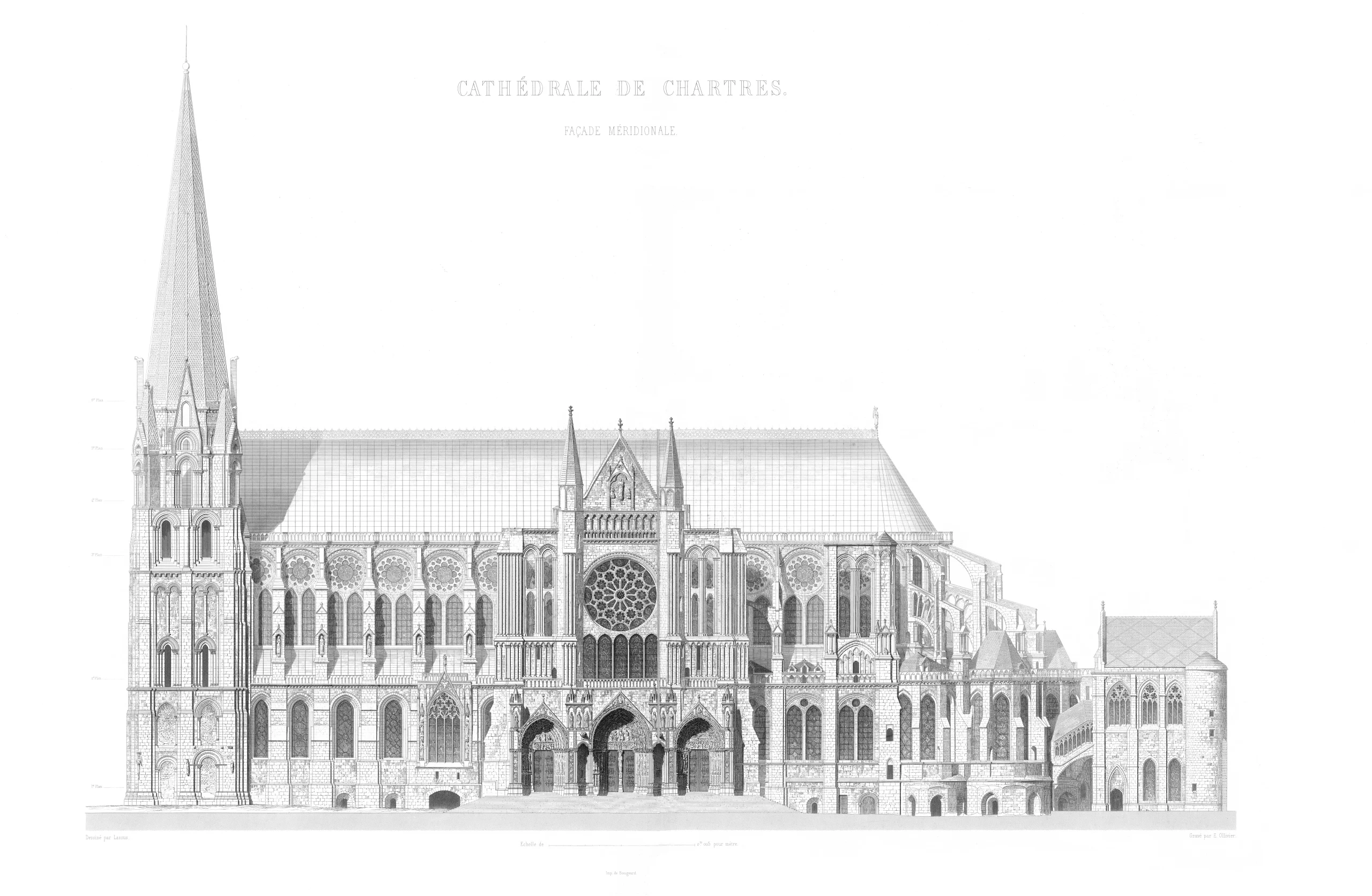

Gothic architecture transformed the medieval built environment about the middle of the 12th century. Gothic architecture emerged from the Romanesque structures in France with the construction of the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Its use of flying buttresses, ribbed vaults, and pointed arches allowed for previously unheard-of levels of light and verticality.

With magnificent façades brimming with sculpture and stained glass windows illuminating interiors with vibrant light, cathedrals such as Chartres, Amiens, and Notre-Dame de Paris towered above the sky. Gothic architecture guided visitors through symbolic ascents toward the divine and was not just about form. It symbolized a worldview in which the harmony of geometric structure and illuminating space revealed divine order.

Renaissance: Back To Classics

Humanism and fresh intellectual perspectives led to the rediscovery of Greco-Roman antiquity during the Renaissance (c. 1400–1600). The asymmetry of Gothic architecture was abandoned by architects, who instead looked to symmetry and proportion as guiding concepts.

The dome of Florence Cathedral, a remarkable technical and design achievement, was created by Filippo Brunelleschi, who is regarded as the founder of Renaissance architecture. The tone of the time was established by his use of perspective, geometry, and classical orders. Using classical proportions as a basis, Leon Battista Alberti published architectural treatises that codified beauty standards.

Later, Andrea Palladio used idealized floor layouts and temple-front porticos to enhance domestic architecture in homes like La Rotonda. Inspiring neoclassical architecture throughout Europe and even colonial America, his impact went much beyond Italy. Through the integration of art, philosophy, and mathematics, architecture was reaffirmed as a learned and intellectual field during the Renaissance.

Rococo and Baroque: Ornament and Power

Baroque (c. 1600–1750) spoke of drama, spectacle, and emotional connection, while the Renaissance spoke of intelligence and equilibrium. Baroque architecture, which originated in Catholic Rome during the Counter-Reformation, aimed to impress the senses and proclaim the Church’s magnificence.

While Francesco Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane subverts traditional rules into vibrant new shapes, Gian Lorenzo Bernini‘s colonnade at St. Peter’s Square welcomes guests in a symbolic act of inclusivity. By utilizing curved façades, dramatic lighting, illusionistic frescoes, and theatrical compositions, baroque design turned palaces and churches into platforms for devotion and authority.

The lighter and more humorous Rococo style replaced the Baroque during the 18th century, especially in southern Germany and France. Pastel colors, gilded stucco, floral themes, and elaborate craftsmanship were characteristics of Rococo interiors, such as those found at the Wieskirche or the Amalienburg Pavilion. Intimate, ornamental, and sensual, it was architecture as a fantasy. Rococo was the pinnacle of interior design and craftsmanship, despite later criticism for its excess.

Neoclassicism

The extravagant Baroque and Rococo styles gave rise to Neoclassicism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Architects went back to the simple lines and civic gravity of classical antiquity after being influenced by the ideas and archeological finds of old ruins.

Roman temples served as the direct inspiration for structures like Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and the Pantheon in Paris. Claude Nicolas Ledoux and Étienne-Louis Boullée experimented with massive forms that fused symbolic clarity with geometric abstraction. The Enlightenment values of order, reason, and civic virtue were reinforced by the employment of neoclassical architecture in government buildings, banks, museums, and churches.

Pre-modern architecture gives fundamental ideas that are still relevant now, in addition to historical nostalgia. Every architect still faces the same challenges today: the dialectic of ornament and structure, the conflict between light and bulk, and the pursuit of balance between form and purpose.

Every period of pre-modern architecture added a chapter to the developing narrative of human desire through architectural form, from the ethereal drama of Baroque façades to the logical symmetry of the Renaissance and the mystical light of Gothic cathedrals. These structures were philosophical declarations and technical marvels, demonstrating how architecture is a reflection of the society that created it.

Leave a comment