In the dictionary of architectural expressions passers-by use to title or describe an architectural object, the ‘blob’ occupies a central position. Hereby, blob refers to everything that is somewhat unusual, round, and organic and oftentimes completely detached in form and/or function from its immediate surroundings. Nevertheless, one can trace down the historic emergence of the ‘blob’ to help oneself to better understand why architects might sometimes opt for a blobby approach to their project or in their design language.

In the following, I will describe the blob – also known as blobism or blobitecture – and lay out the emergence of this concept. After that, I will give examples of when blobitecture is used and why, sometimes perhaps, it can make sense.

What is a blob?

To add order to the emergence of blobism, one needs to read all articles existing about it – which are not many. The definition of blobism is closely entangled with its emergence, which is mainly yet not only due to advances in computer software, or better: CAD programs. Generally, it can be said that blobitecture is an organic, often curved way of designing buildings. The better but slightly downgrading term used is amoeba-shaped. In that sense, blobism describes a building that was impossible to be designed before the emergence of CAD programs on a larger scale, due to problems to calculate its structural integrity. To be even more precise, American architect Greg Lynn describes blobism as a biomorphic form, or, more straight to the point, describes a BLOB as a Binary Large Object.

Of course, in the public discourse, when the word blob is mentioned, it is not a reference to blobism but rather subconsciously questions the architect’s ability to design; whereas the blob is actually some kind of testimony of architects mastering their programs, just as they mastered their pencils before.

In An Engineer Writes, the author states: “We have architect Greg Lynn to thank for the original term – he invented it in 1995 to give definition to his experiments in digital design. He used metaball software, the technique for which had been invented by Jim Blinn (a NASA computer scientist) in the first years of the 1980s. This blobby modeling (real term) enabled the creation of organic-looking n-dimensional objects, where n is the number of dimensions (usually 2 or 3) being measured.” A British architectural office called Alastair Macnab Architects continues the story: “One of the early examples of blob architecture was created in the 1960s by a handful of English architects known as Archigram, a group that included Peter Cook and Ron Herron, working with inflatable structures and designs using plastic.

Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes were another stage in the evolution of blobism or blobitecture, but the first reported use of the term blobitecture is attributed to William Safire in his 2002 article in the New York Times Magazine; it was not meant as a compliment.” And “[t]echnically” continues the first blog, “The first building designed through pure blob architectural techniques was the Water Pavilion, a temporary structure in Holland which stood from 1993 – 1997. It was built by Lars Spuybroek (NOX) and Kas Oosterhuis and was of a fully computer-based nature. Its interior was fully electronically interactive – light and sound could be changed by visitors.”

It is, of course, less relevant which of these buildings and projects was the first, but more relevant it is to understand the shift between blobism pre-CAD and blobism post-CAD. In other words: Blobism is a formal expression and an expression of technical possibility. Nevertheless, the blob meant novelty and so it is no surprise that the first blob buildings are sharply remembered. Alastair Macnab Architects continue: “In the UK, most observers agree that the first example of ‘true’ blob architecture was Selfridge’s Department Store in Birmingham. From a distance, the building does bear a remarkable resemblance to a beached whale, but it certainly does the job its creators intended. Aptly named Future Systems, designers of the building, said it was never meant to complement the existing skyline; they wanted an “architectural landmark” and they got it.”

For what the blob is worth

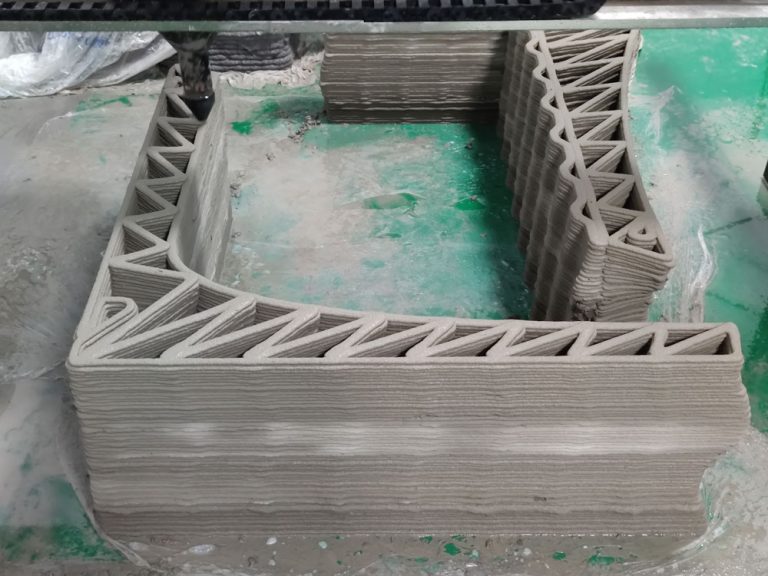

A blob can be a landmark, an architectural transition, a statement of technological advance or advantage over neighboring projects, or even a fitting for the purpose. The conscious use of the blob as an architectural object is supported by a statement from another blog called Layak Architect notes: “This style is expensive, and historically it has been limited by the performance of materials as it requires custom-made materials that are not easily manufactured or found in nature. They need to be custom-made, and highly skilled craftsmanship is required to build these kinds of shapes and forms. With the advancement and precision of technology, it is now done with proper measures and considerations.” And further: “Steel and glass are important elements in blob constructions. Solar panels, color-changing plastic blocks, glass panels with integrated led strips, and other new-generation materials were created to meet the needs of the building.”

A blob that is meant to last is hereby to be distinguished from a blob that is part of an installation, such as Plastique Fantastique in Berlin who are using inflatables for different purposes.

Generally, Layak Architect continues, “[t]his architectural style can only be found in large buildings like concert halls, art museums, airports, and other large public spaces.” In other words: There are few residential buildings that can be called a blob, which may be due to fewer representational functions and the need to maximize space.

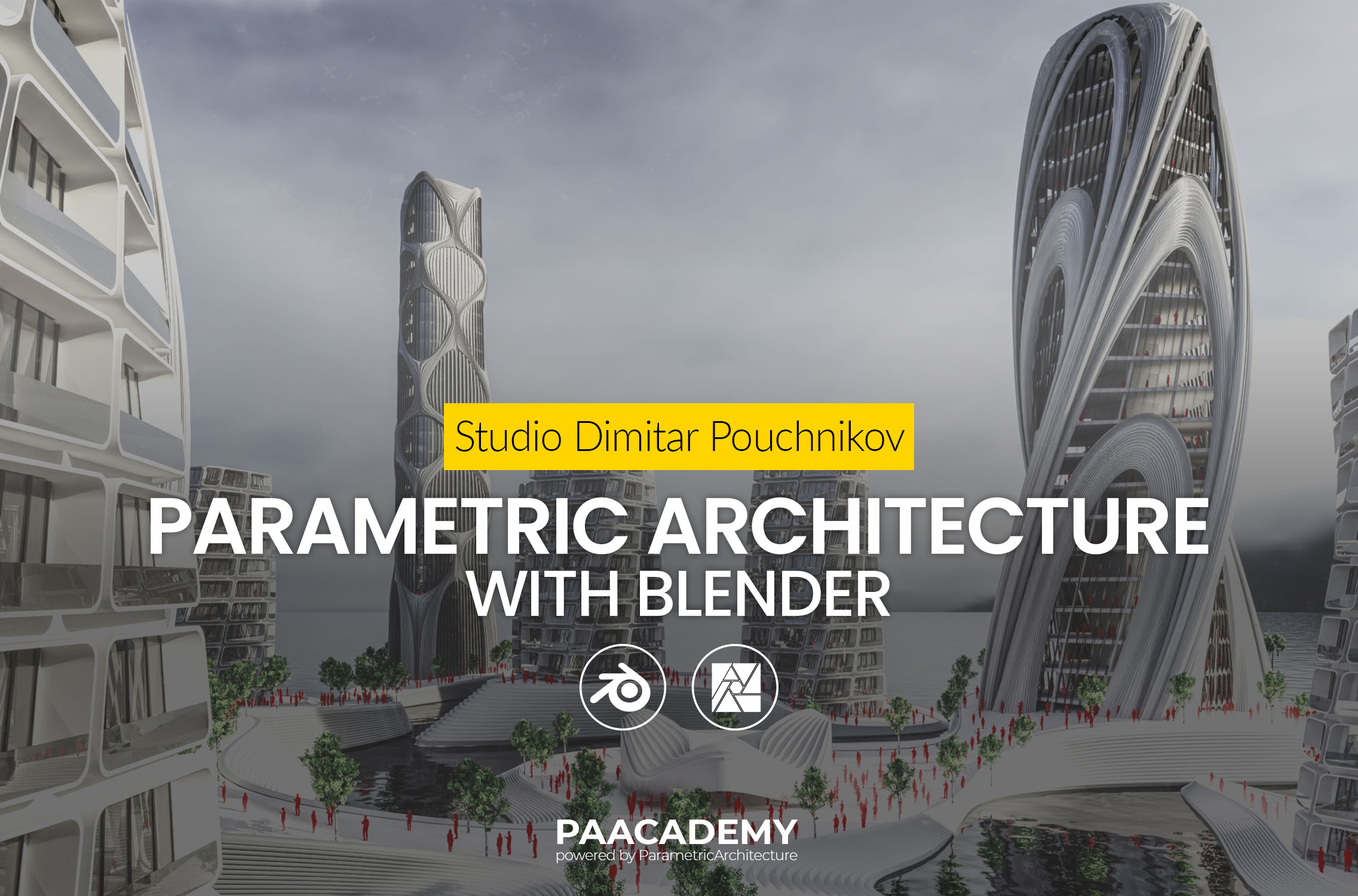

On the other hand, one may also ask how a modern-day blob has changed in form and style: Whereas the word ‘blob’ and its architectural form are onomatopoetic, that is, the word sounds as what it refers to, a modern-day blob may be less organic or amoeba-shaped. One can see other forms – such as through parametric architecture – being of a similar origin and for similar purposes. In what ways, becomes the questions, are many of the works of famous contemporary architects less blobby?

Even the more edgy and parametrically designed works of BIG and Zaha Hadid Architects have traces of the blob. That is because they are often intentionally different from their surroundings and only abstractly reflect them and further, they are testimonies of another software advance such as the blob was once. One could even make the analogy that all these different forms architects have produced in the recent decades are different attempts to “[…] imitate the beauty of nature, in which straight lines and right angles are exceptions rather than the rule” – as Layak Architect states further. Architects might therefore subconsciously seek to imitate nature’s complexity, and every new style that offers a new approach to doing that is welcomed.

In the last bit, we would like to display three examples of blob-architecture according to the three identified uses: The blob as a landmark, as an urban transition, and as best fitting for the purpose (or site). By now it is clear from which analog experimentations and advances in CAD programs the blob emerged and therefore what people may (want to) refer to when they say blob, but now it is time to think more actively about its purposes. The first of these is the blob as a landmark – a Lynchian term – here illustrated by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier’s iconic Kunsthaus Graz. This needs no further explanation and the image displays how different the blob appears from its immediate surroundings.

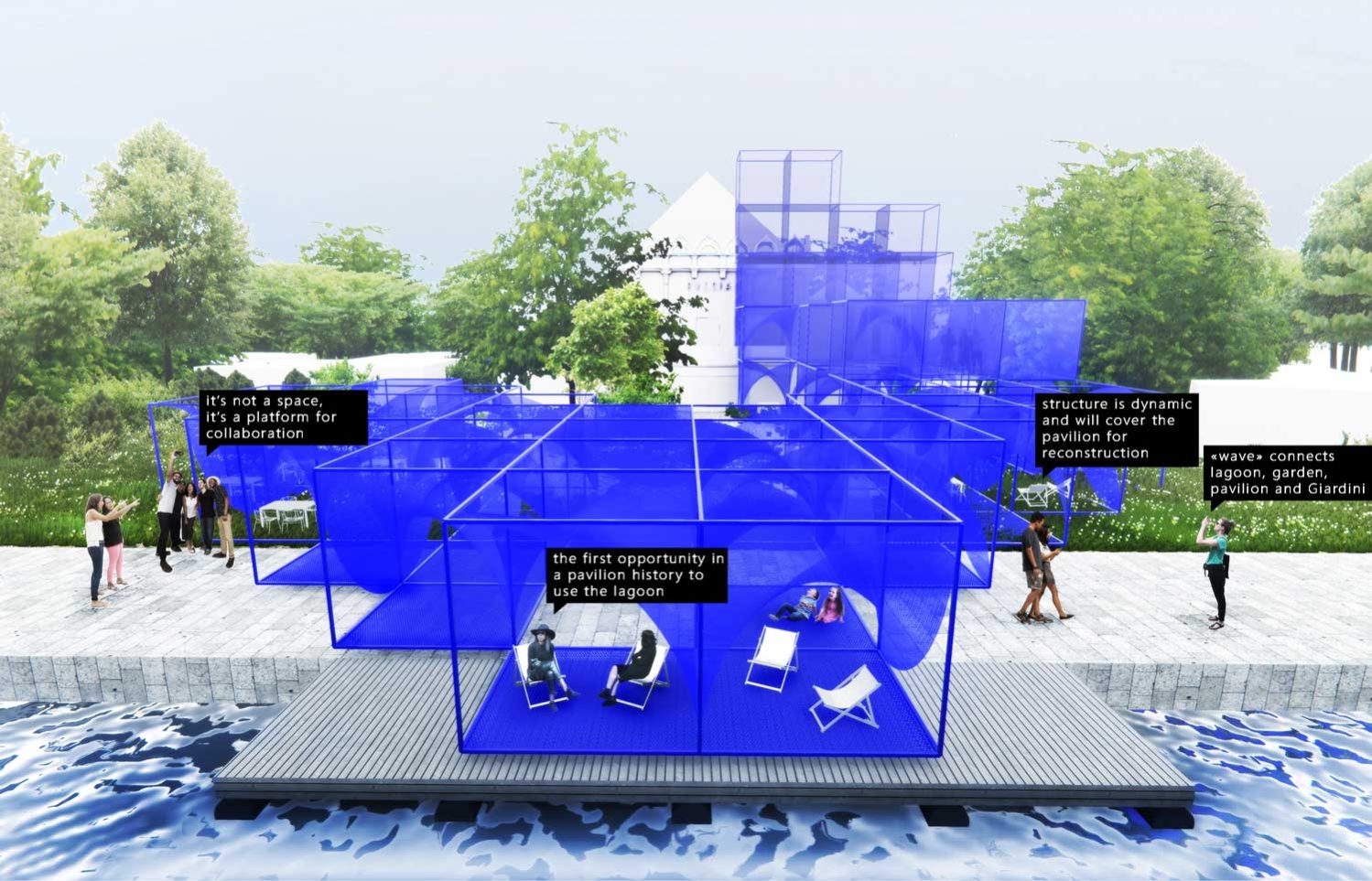

The second example is the Golden Terraces (Polish: Złote Tarasy) in Warsaw, erected in 2007 by American Architects Jerde Partnership. The terraces serve as a roof to a shopping mall, yet also achieve a transitional effect between the mall and the walkable terraces – from a further distance even to the central train station.

The third example is “The Bean”, officially named “Cloud Gate”, in Chicago by Indian-born British artist Anish Kapoor, which opened in 2004. Although clearly a landmark too, visitors may enter the park within which the sculpture sits through the gate that opens up underneath. More importantly, the sculpture reflects people, the surrounding buildings, and the sky, leading visitors to slow down their pace (and somewhat) meditate for a second.